On Thursday, Boston’s best-loved psychiatrist was back on our screens after an almost 20-year absence. Kelsey Grammer might have been the sole key cast member returning for Paramount’s Frasier reboot, yet the anticipation surrounding his comeback – and the warmth that met him – is testament to undiminished audience appetite for 90s sitcoms.

A Friends reunion show in 2021 became Sky One’s most viewed programme ever. And, last weekend, the possibility of a fresh instalment of the holy grail of small-screen multi-camera comedies suddenly came closer.

Speaking on his standup tour in the US on Saturday, Jerry Seinfeld told a Boston audience he “has a little secret” about the show, whose 1998 finale was watched by 76 million viewers in the US when it first aired, but whose plot – the four friends go on trial for wisecracking when a man is mugged in front of them – proved divisive.

“Something is going to happen that has to do with that ending. It hasn’t happened yet,” Seinfeld said. “Just what you are thinking about, [co-creator] Larry [David] and I have also been thinking about. So, you’ll see.”

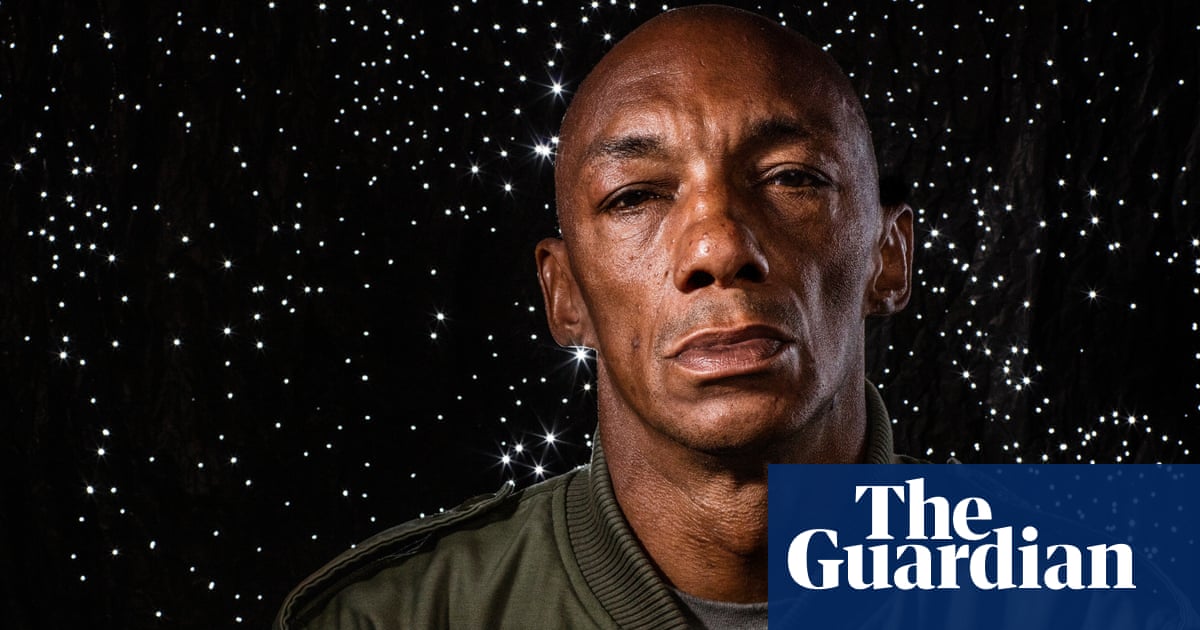

His words triggered heated speculation all week about what form such a show might take. Stars Jason Alexander and Michael Richards are yet to offer comment, but speaking to the Guardian on Wednesday, Julia Louis-Dreyfus, who played Elaine Benes on the programme, which ran between 1989 and 1998, professed ignorance about any such endeavour.

“Yeah, I just saw [that news] last night,” she said. “And I don’t know what the hell he’s talking about.”

Of all the Seinfeld actors, Louis-Dreyfus is the one who appears to need such a return the least. As well as starring in subsequent hit TV shows such as Veep, the actor has won acclaim on the big screen, most notably for her roles in Nicole Holofcener’s cerebral and sensitive comedies Enough Said (2013) and You Hurt My Feelings (2023).

Her latest project further dramatically expands that range. Tuesday, a contemporary fairytale about grief, had its UK premiere at the London film festival earlier this week, picking up considerable Oscar buzz for Louis-Dreyfus’s performance.

She plays a single mother in denial about the terminal illness of her teenage daughter, Tuesday, played by Lola Petticrew. When the grim reaper arrives in the form of a massive, talking macaw, both women try to defer the inevitable by bargaining, battling – and vaping with – Death.

Critics praised Louis-Dreyfus as “a revelation” – particularly in sequences that see her unleashing a primordial energy unfamiliar to regular fans. “She’s a performer whose radiant ferocity has never been in doubt,” wrote the Hollywood Reporter, “but until now we haven’t [sic] seen all sides of the prism.”

Shooting the film in London last year was, says Louis-Dreyfus, “was really rough. There were a few days filming the most challenging stuff when I really thought I was gonna lose my mind.”

Trusting first-time director Daina Oniunas-Pusic was decisive, says Louis-Dreyfus. “I really have to go to a pretty unsafe place to do this properly. I wanted to make sure that in her care I would be OK.

“It was really scary, actually. I was away from what I was most comfortable with doing something very uncomfortable. So it made me particularly feel uprooted and discombobulated. The only way to combat that was either [to dive] headfirst into work or get the fuck out and get home.”

Pushing her star was necessary for the film, says Oniunas-Pusic. “You don’t really get signs someone is going to act in a certain way, because people are well-equipped at presenting themselves. But when push comes to shove, if they’re cornered, they will do anything the wiring of their brain demands them to.”

Both Dreyfus, 62, and Petticrew, 27 – best known for the film Dating Amber and BBC One series Bloodlands – report having left the shoot better equipped to discuss mortality.

“Conversations around death and dying are understandably limited and fraught,” says Louis-Dreyfus. “I’ve lost close people in my family and it’s gutting every time. You don’t consider that people will die, which is completely irrational, but it’s what we must do to live. Yet there is value in talking about this stuff.”

To daydream about one’s own death, adds Louis-Dreyfus – who was successfully treated for breast cancer in 2017 – is also “a human thing. Who doesn’t do that?” A good death, she says, would be “one without pain. That would be a delight. Surrounded by loved ones.”

Petticrew says: “I’m gonna try to make the best out of this life, and if I get to see my dog and my parents once it’s done, it’s a complete utter bonus. If I just become part of the energy that feeds trees or stars that’s kind of class as well.”

Petticrew was born in Belfast after the ceasefire and shares a belief with Oniunas-Pusic – who is 38 and from the Balkans – that those raised in volatile environments approach death differently.

In Ireland, says Petticrew, “it’s very reverent, but there’s also big wakes where we celebrate life and you wouldn’t catch anybody sitting, crying and weeping. There’s lots of drinking and dancing and remembering.”

For people raised amid violence, agrees Oniunas-Pusic, “there tends to be a lightness of touch and a sense of acceptance of the timeframe that mortality offers, giving meaning to life.”

Yet all three are conscious that the recent horrors of the Israel-Hamas war serve as a terrible rebuttal to the film’s suggestion every death involves a measure of rationality or benevolence.

“Life can be absolutely miserable for people,” says Louis-Dreyfus, in response to a comparison between scenes of terrible purgatory in the film and current events in the Middle East.

For Petticrew, the constant access to seeing such news online can have a dismaying effect. “Mass deaths on the other side of the world are right there in your face yet can feel so far removed from your life. It’s something I find really difficult.

“Our brains aren’t meant to process that amount of information. It’s changing the fabric of us. You can see a rise in anxiety in generation Z. You have to care about everything, and when you can’t you start feeling like an awful person.”

Louis-Dreyfus also credits a cultural degradation including gun-toting video games with inuring people to violence. “I feel almost like we’re desensitised. We see so much crap all the time. I don’t think it’s good for our brains. That kind of trauma is nothing anybody should become used to.”

In the film, Tuesday must help her mother navigate the imminent loss of her daughter, and this kind of role reversal, said Petticrew, who is non-binary, will be familiar to their generation.

“Parents sometimes have that way of making your grief and sadness about them. I remember when I came out my mum being like: ‘Why did you feel like you couldn’t come to me for so long?’

“And as lovely and kind and caring and accepting as that was, I was like: ‘It’s not about you. Let me have my thing.’”

The actor was raised Catholic but has since moved towards agnosticism; Louis-Dreyfus also says she doesn’t have any “traditional religious affiliation”. “But I do believe in something. I believe in spirituality. In the mystery of life.”

Yet she will admit to attempting deals in her head with “whoever’s in charge”; trading future better behaviour for positive outcomes. “I have to watch it because I’m very superstitious. I have to make sure that I don’t allow too much of that to enter my life because I can make myself pretty nuts about it.”

Her gamble to star in Tuesday appears to have paid off, with critics wide-eyed and the way paved for more serious projects – whether or not they are interrupted by a return to Seinfeld. As for her own future legacy? “I don’t know! Who the hell knows?”