Not a great deal is known about Carlo and Luciana, it seems. They came from Vignola, a small Italian city near Modena and not far from Bologna. They married and honeymooned. Carlo worked as a clerk in a hardware store and Luciana worked as a tailor. They retired. They spoke only Italian. They were childless. Luciana died first, Carlo several years later.

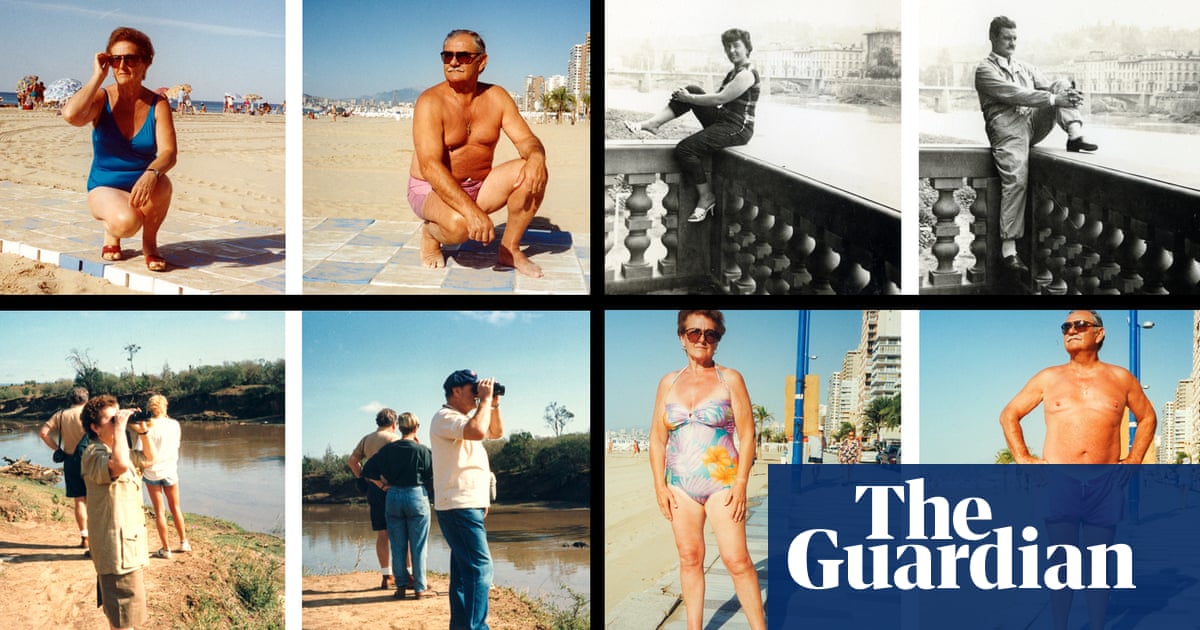

When they had the opportunity, they liked to travel. And travel they did – to China, Cuba, India, Thailand, the Red Sea, America and beyond. The reason we know so much about their holidays is because of the photo albums they made, filled with the portraits they took of each other, always pictured in exactly the same spot.

Their pictures are the subject of an exhibition in Bologna, part of the city’s Foto/Industria festival, by curator and self-styled “photographer without a camera” Erik Kessels, a longtime curator, editor and repurposer of amateur, “found” and vernacular photography.

For more than 20 years Kessels has been riffling through once precious, now unwanted, photo albums, finding the work of amateurs who, as he puts it, “without them knowing, make a beautiful narrative or document of their lives, sometimes with lot of mistakes, sometimes in a very beautiful way”.

I have around 15,000 family albums and 99% are boring – they are only landscapes or waterfalls or boats or cars

He often makes his finds in flea markets, or by buying online, or occasionally through more direct contact. “Sometimes a person rings my doorbell with a bag of albums, saying: ‘I won’t live that long any more and I want you to have them.’ Mostly it’s not interesting, of course,” he laments.

“I have around 15,000 family albums that I have bought over time, and 99% of those 15,000 are fucking boring. They are really horrible because they are only landscapes or waterfalls or boats or cars.”

On this occasion, Sergio Smerieri, a studio owner and neighbour of Carlo and Luciana’s who had helped the couple print and compile their photos, brought the work to his attention. Kessels, always looking for personal documents to use as working material, was undeterred by the prosaic content. “There are still a lot of stories to tell behind existing or mundane images,” he says.

Carlo and Luciana began travelling, by motorbike and later in their Fiat, when they were young, and when snapshots were black and white. By their mid-20s, though, it appears that work commitments curtailed their activities. Certainly they took no photos until their retirement 40 years later. Then their package holidaying began in earnest. “They started again,” says Kessels, “they travelled all over the world, and always did the same trick.”

With the couple’s adherence to a rigid pictorial protocol and a deadpan systematicity, their pictures could be mistaken for those of a pair of itinerant conceptual artists. Kessels concedes that is one way of viewing the work, but he stresses that for a couple travelling alone, “this was purely practical for them. That’s why I quite like it.

“Carlo and Luciana had no children. They didn’t do this as an artistic act – they just did it out of practical reasons. Of course there were no selfie sticks or other ways of making the picture. He took a picture of her, and she of him in the same spot, and then they put them next to each other in the album so they have, in a way, one image with both of them in it.”

For Kessels, presenting the pictures in a new context offers an opportunity for them to be re-evaluated. “Just by taking them out of their context and putting them in a book or an exhibition, people start to look at them differently. I didn’t crop them; I never do anything to the colour; I never retouch them. In my case the edit is important. How to exhibit it is like my act of reappropriation.”

As part of his reimagining of the holiday snaps, Kessels takes pains to include the 40-year hiatus that interrupts the albums. He displays blank panels in the exhibition, and 40 white pages in a book of the work. “The beautiful thing in this case is that there are 40 years without any image and that is quite special,” he says.

One reason the dual portraits hold such appeal for him is that they predate the era of selfie sticks, social media and filter apps.

“In a way that’s also what I’m interested in. I mean nowadays maybe people are much more aware of what they do because we grow up now in an image culture. With a mobile phone and its images you are very aware that you can be quite artistic, or that people have seen there are certain ways of doing things that are interesting.”

Not so for Carlo and Luciana.

And, unlike the original albums which were arranged by country and dated, he is reluctant to include caption material. He prefers, he says, “to try to make people pause, to look at the images first, and slowly maybe imagine your own story”.

“I’m always searching in people’s very mundane albums for very specific stories. I’m almost like a visual archaeologist,” he says. “Sometimes the images are quite clear and the narrative is quite clear. Sometimes I need to look at it and digest it and wait and see before I get the idea of ‘OK it’s about this.’ That is the nice part of it – it’s a puzzle sometimes.”

Carlo and Luciana is on display in Bologna as part of the Foto/Industria festival until 26 November.

Carlo and Luciana, edited by Erik Kessels and Sergio Smerieri, is published by Kesselskramer.

This interview was made possible with the assistance of Foto/Industria