Hebert Amorim was eight when he got his first taste of funk carioca (Rio funk): a pirate CD by Mr Catra, a favela MC famed for his ferociously explicit verses about gangs, guns and sex.

“My mum caught me listening to it and went mental,” said the 30-year-old visual artist from Senador Camará, a hardscrabble corner of west Rio de Janeiro where police fear to tread.

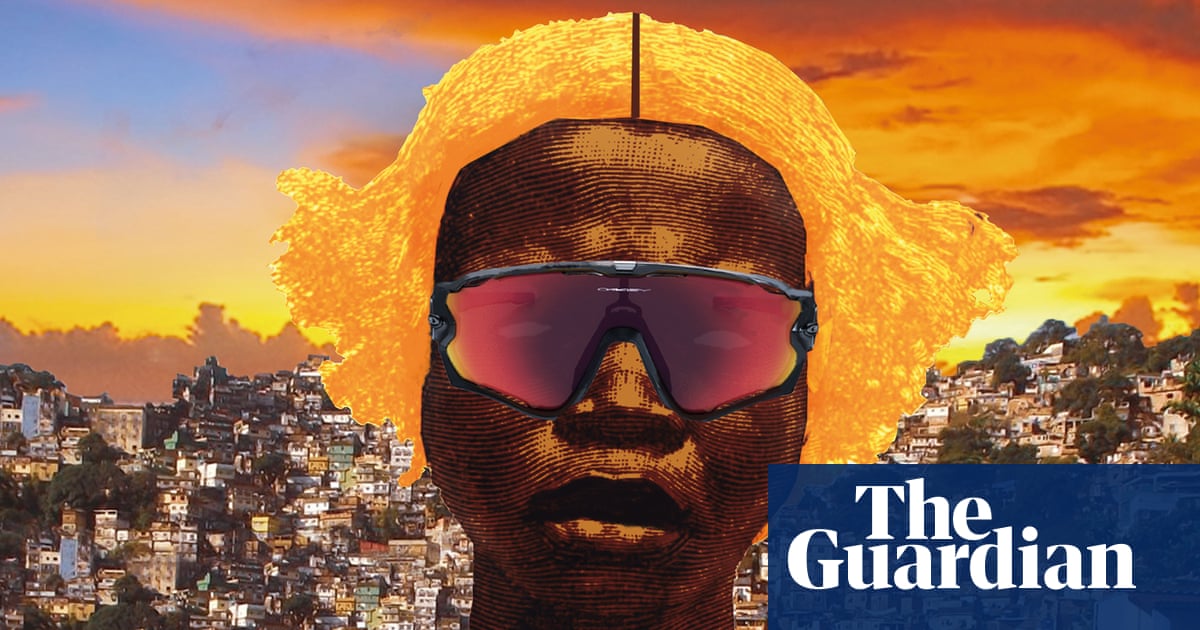

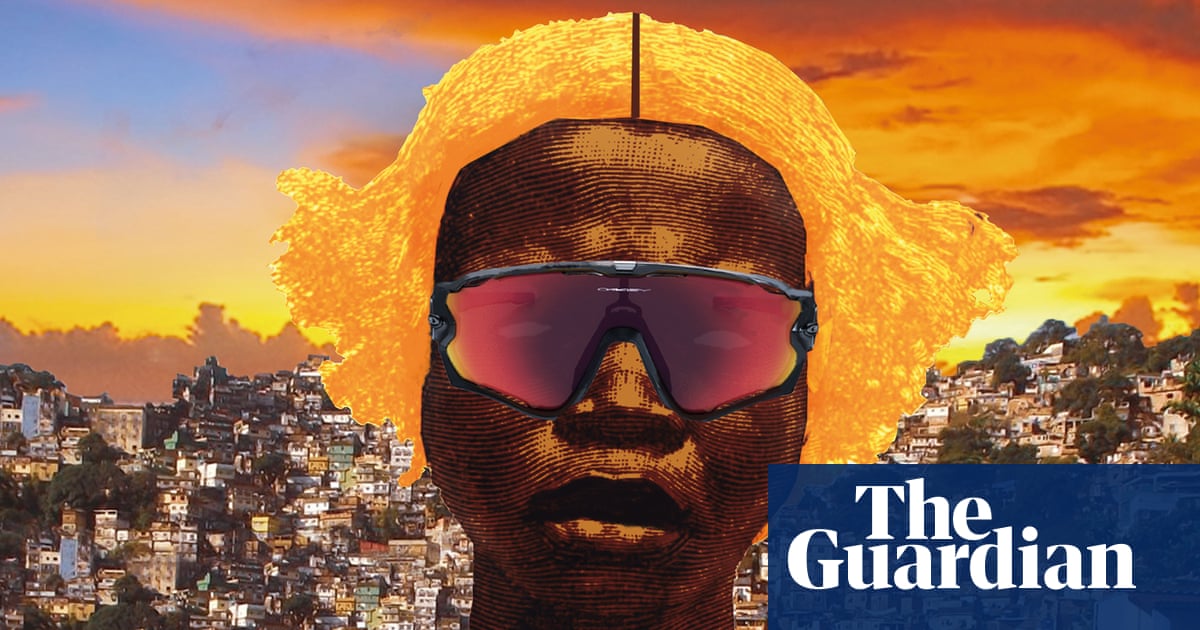

Amorim was hooked. A few years later he sneaked off to his first favela funk party, telling his mum he was staying at a friend’s. “I got there and just went: ‘What is this? There was this surreal energy,” he said, describing the electrifying collision of DJs, dancers, weaponry and bling that he witnessed and now recreates in his collages.

Amorim’s compositions are among 900 pieces in a new exhibition at Rio’s Museum of Art (MAR) celebrating the funk movement and its role in Brazilian society, culture and politics. The show – which features some of Brazil’s most acclaimed young artists, as well as foreigners such as the photographer Vincent Rosenblatt – is reputedly the first time a leading museum has devoted an entire exhibition to the genre.

More than three decades after the birth of funk carioca – which boasts more than half a dozen subgenres and lyrics that can be smutty, frivolous, politically aware or downright illegal in their glorification of gangland life – debate still rages over its roots. Some call it a South American fusion of Miami bass and gangsta rap. Others believe it derives from an Afro-Brazilian rhythm called Maculelê.

Marcelo Campos, MAR’s curator-in-chief, said the show was a deliberate rebuttal to art snobs who believed museums should only display the “high culture” of Brazil’s predominantly white elites and considered funk “the stuff of outlaws”.

“It’s an exhibition that seeks to completely turn the page on the idea of funk being a taboo,” Campos said during a tour of the show’s two halls – one focusing on Rio’s black history and another on the favela funk movement itself. “Our message is that [funk] is absolutely top-notch culture.”

For Amorim, the surprise was not that an important museum was hosting a show about funk, but that this had not happened before. “In truth it was long overdue. Funk is one of the greatest – if not the greatest – legacy of our times,” the artist said, as he sat on his roof surveying the area that inspires his work.

The MAR exhibition places funk in a century-long tradition of black culture, resistance and empowerment stretching back to music legends such as the flautist and saxophonist Pixinguinha, early last century. The precursors of today’s favela funk bailes (dances) began in the 1970s, as music lovers packed suburban nightclubs to groove to the sound of James Brown and Kool & the Gang.

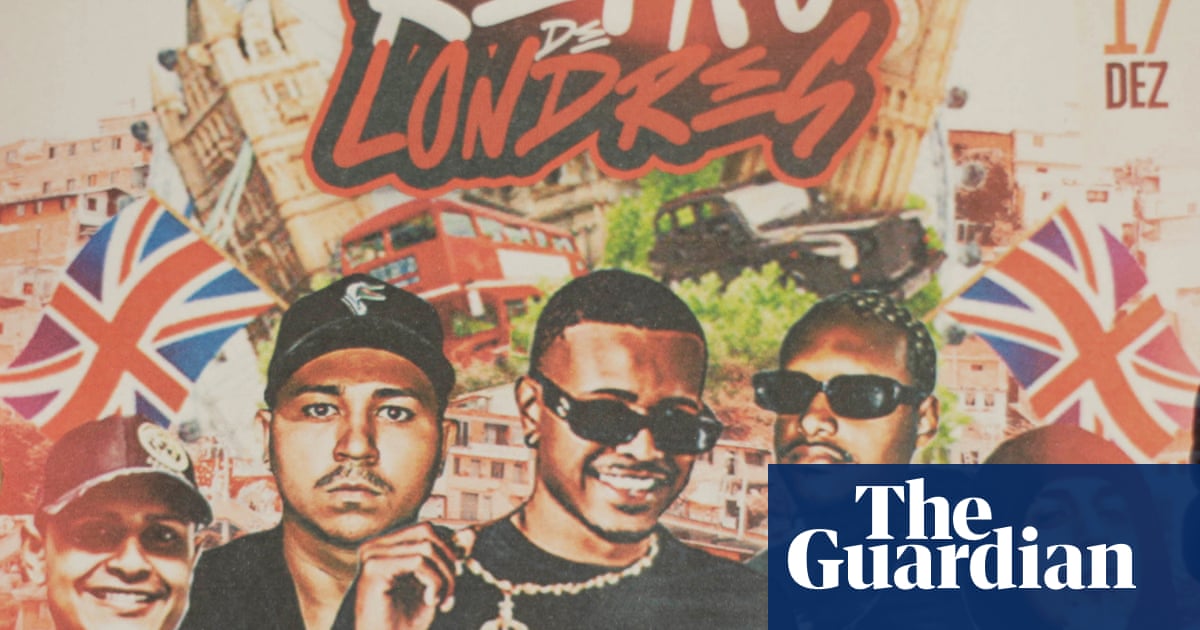

Those soul and funk dances later moved inside the favelas – today home to 20% of Rio’s 6.6 million inhabitants – and became a deafening cultural and social phenomenon as Amorim grew up in the 1990s and 2000s. Today, Rio’s biggest bailes – many named after foreign countries or cities including Egypt, the Netherlands, Moscow and London – attract tens of thousands of revellers and are a key part of the local economy.

“You can forget about sleeping when a funk party’s happening. It’s like the music’s playing inside your home,” Amorim said of the ear-splitting all-night raves that take place near his childhood home.

Amorim called funk a way of chronicling and celebrating the hard-knock realities of Rio’s favelas, control of which authorities have largely surrendered to the heavily armed drug factions. “Funk is about telling the naked truth of life. Funk is the reality we live,” he said. “It’s the thing everyone sees but nobody wants to discuss.”

Amorim, whose artistic name is Artedeft, hoped to achieve something similar with his collages, which mix scenes of favela life with “samples” from painters including Van Gogh, Edvard Munch and Paul Gauguin. “I talk about a Rio that’s right in front of me – if you look out at the street you’ll see my art, whichever way you look,” said the artist, who did not visit an art museum until seeing a Salvador Dalí retrospective when he was 21.

Another artist in the show, Juan Calvet, 25, said he cried after receiving MAR’s invitation. He had visited his first museum only three years before. “It’s a really powerful experience, you know? Coming to the museum and seeing yourself in so many different ways,” Calvet said.

Museumgoers from the favelas voiced similar sentiments as they snapped selfies with funk-inspired sculptures and canvases that spoke to their lives.

“I saw myself,” said Andreia Sampaio da Silva, a fortysomething-year-old trans woman, reminiscing about the bailes de corredor (“corridor dances”) she frequented in her youth, where rival funk collectives held dance-offs that often turned violent.

Campos thought deep-rooted intolerance and elitism explained why museums had previously shunned funk and the favelas.

“Funk suffers the same prejudice samba suffered. Samba was also considered the stuff of outlaws. People were arrested. Shows shut down. Lyrics banned,” said the curator, who wanted MAR to challenge such preconceptions with exhibitions reflecting contemporary society.

“There’s no point in continuing to think – as people have for so long – that the best thing to do here is educate society by exhibiting a Mona Lisa. That no longer cuts it.”