To begin with, let me tell you a story. There were once two jackals: Karataka, whose name meant Cautious, and Damanaka, whose name meant Daring. They were in the second rank of the retinue of the lion king Pingalaka, but they were ambitious and cunning. One day, the lion king was frightened by a roaring noise in the forest, which the jackals knew was the voice of a runaway bull, nothing for a lion to be scared of. They visited the bull and persuaded him to come before the lion and declare his friendship. The bull was scared of the lion, but he agreed, and so the lion king and the bull became friends, and the jackals were promoted to the first rank by the grateful monarch.

Unfortunately, the lion and the bull began to spend so much time lost in conversation that the lion stopped hunting and so the animals in the retinue were starving. So the jackals persuaded the king that the bull was plotting against him, and they persuaded the bull that the lion was planning to kill him. So the lion and the bull fought, and the bull was killed, and there was plenty of meat, and the jackals rose even higher in the king’s regard because they had warned him of the plot. They rose in the regard of everyone else in the forest as well, except, of course, for the poor bull, but that didn’t matter, because he was dead, and providing everyone with an excellent lunch.

This, approximately, is the frame-story of On Causing Dissension Among Friends, the first of the five parts of the book of animal fables known as the Panchatantra. What I have always found attractive about the Panchatantra stories is that many of them do not moralise. They do not preach goodness or virtue or modesty or honesty or restraint. Cunning and strategy and amorality often overcome all opposition. The good guys don’t always win. (It’s not even always clear who the good guys are.) For this reason they seem, to the modern reader, uncannily contemporary – because we, the modern readers, live in a world of amorality and shamelessness and treachery and cunning, in which bad guys everywhere have often won.

I have always been inspired by mythologies, folktales and fairytales, not because they contain miracles – talking animals or magic fishes – but because they encapsulate truth. For example, the story of Orpheus and Eurydice, which was an important inspiration for my novel The Ground Beneath Her Feet, can be told in fewer than 100 words, yet it contains, in compressed form, mighty questions about the relationship between art, love and death. It asks: can love, with the help of art, overcome death? But perhaps it answers: doesn’t death, in spite of art, overcome love? Or else it tells us that art takes on the subjects of love and death and transcends both by turning them into immortal stories. Those 100 words contain enough profundity to inspire 1,000 novels.

The storehouse of myth is rich indeed. There are the Greeks, of course, but also The Norse Prose and Poetic Edda. Aesop, Homer, the Ring of the Nibelung, the Celtic legends, and the three great Matters of Europe: the Matter of France, the body of stories around Charlemagne; the Matter of Rome, regarding that empire; and the Matter of Britain, the legends surrounding King Arthur. In Germany, you have the folktales collected by Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm.

However, in India, I grew up with the Panchatantra, and when I find myself, as I do at this moment, in between writing projects, it is to these crafty, devious jackals and crows and their like that I return, to ask them what story I should tell next. So far, they have never let me down. Everything I need to know about goodness and its opposite, about liberty and captivity, and about conflict, can be found in these stories. For love, I have to say, it is necessary to look elsewhere.

And what does the world of fable have to tell us about peace? The news is not very good. Homer tells us peace comes after a decade of war when everyone we care about is dead and Troy has been destroyed. The Norse myths tell us peace comes after Ragnarök, the Twilight of the Gods, when the gods destroy their traditional foes but are also destroyed by them. The Mahābhārata and Ramayana tell us peace comes at a bloody price. And the Panchatantra tells us that peace is only achieved through treachery.

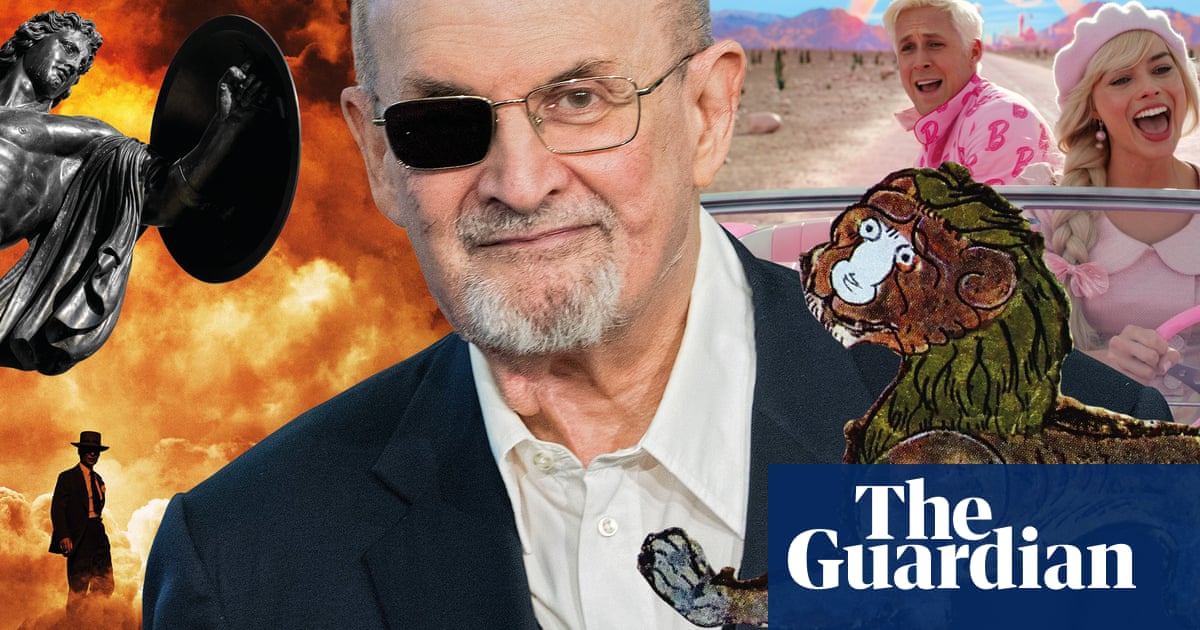

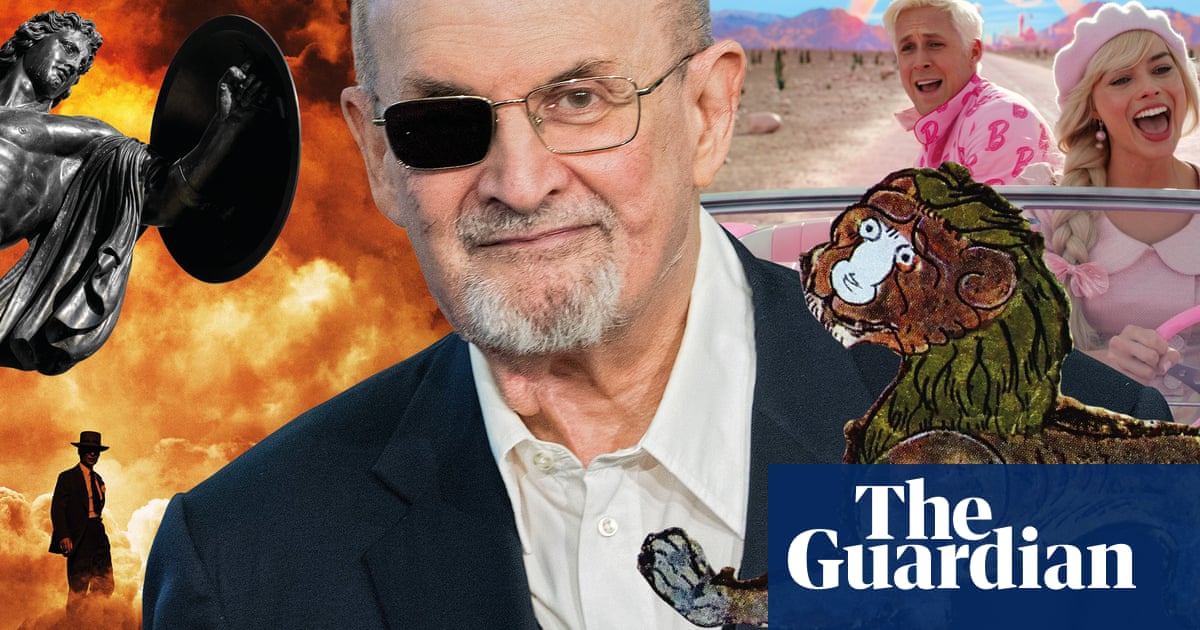

But let’s abandon the legends of the past for a moment to look at this summer’s twin legends: I’m referring of course to the movie double-header known as Barbenheimer. The film Oppenheimer reminds us that peace only came after two atom bombs, Little Boy and Fat Man, were dropped on the people of Hiroshima and Nagasaki; while the box-office monster called Barbie makes clear that unbroken peace and undiluted happiness, in a world where every day is perfect and every night is girls’ night, only exist in pink plastic.

And we speak of peace now, when war is raging, a war born of one man’s tyranny and greed for power and conquest; and another bitter conflict has exploded in Israel and the Gaza Strip. Peace, right now, feels like a fantasy born of a narcotic smoked in a pipe. Peace is a hard thing to make, and a hard thing to find. And yet we yearn for it, not only the great peace that comes at the end of war, but also the little peace of our private lives, to feel ourselves at peace with ourselves, and the little world around us. It is one of our great values, a thing ardently to pursue. There is also something decidedly fabulist about the notion of peace prizes. But I like the idea that peace itself might be the prize, a whole year’s supply of it, delivered to your door, elegantly bottled. That’s an award I’d be very happy to receive. I am even thinking of writing a story about it, The Man Who Received Peace as a Prize.

I imagine it taking place in a small country town, at the village fair, maybe. There are the usual competitions, for the best pies and cakes, the best watermelons, the best vegetables; for guessing the weight of the farmer’s pig; for beauty, for song, and for dancing. A pedlar in a threadbare frock-coat arrives in a gaily painted horse-drawn wagon, looking a little like the itinerant confidence trickster Professor Marvel in The Wizard of Oz, and says that if he is allowed to judge the contests he will hand out the best rewards anyone has ever seen. “Best prizes!” he cries. “Roll up! Roll up!”

And so they do roll up, the simple country folk, and the pedlar hands out small bottles to the various prizewinners, bottles labelled Truth, Beauty, Freedom, Goodness, and Peace. The villagers are disappointed. They would have preferred cash. And in the year following the fair, there are strange occurrences. After drinking the liquid in his bottle, the winner of the Truth prize begins to annoy and alienate his fellow villagers by telling them exactly what he really thinks of them.

The Beauty, after drinking her award, becomes more beautiful, at least in her own eyes, but also insufferably vain. Freedom’s licentious behaviour shocks many of her fellow villagers, who conclude that her bottle must have contained some powerful intoxicant. Goodness declares himself to be a saint and of course after that everyone finds him unbearable. And Peace just sits under a tree and smiles. As the village is so full of troubles, this smile is extremely irritating, too.

A year later when the fair is held again, the pedlar returns, but is driven out of town. “Go away,” the villagers cry. “We don’t want those sorts of prizes. A rosette, a cheese, a piece of ham, or a red ribbon with a shiny medal hanging from it. Those are normal prizes. We want those instead.”

I may or may not write that story. At the very least, it may serve lightheartedly to illustrate a serious point, which is that concepts we think we can all agree to be virtues can come across as vices, depending on your point of view, and on their effects in the real world.

My fate, over the past many years, has been to drink from the bottle marked Freedom, and therefore to write, without any restraint, those books that came to my mind to write. And now, as I am on the verge of publishing my 22nd, I have to say that on 21 of those 22 occasions, the elixir has been well worth drinking, and it has given me a good life doing the only work I ever wanted to do.

On the remaining occasion, namely the publication of my fourth novel, I learned – many of us learned – that freedom can create an equal and opposite reaction from the forces of unfreedom. I learned, too, how to face the consequences of that reaction, and to continue, as best I could, to be as unfettered an artist as I had always wished to be. I learned, too, that many other writers and artists, exercising their freedom, also faced the forces of unfreedom, and that, in short, freedom can be a dangerous wine to drink.

But that made it more necessary, more essential, more important to defend, and I have done my best, along with a host of others, to defend it. I confess there have been times when I’d rather have drunk the Peace elixir and spent my life sitting under a tree wearing a blissful, beatific smile, but that was not the bottle the pedlar handed me.

We live in a time I did not think I would see, a time when freedom – and in particular, freedom of expression, without which the world of books could not exist – is everywhere under attack from reactionary, authoritarian, populist, demagogic, half-educated, narcissistic, careless voices; when places of education and libraries are subject to hostility and censorship; and when extremist religion and bigoted ideologies have begun to intrude in areas of life in which they do not belong. And there are also progressive voices being raised in favour of a new kind of bien-pensant censorship, one that appears virtuous, and which many people, especially young people, have begun to see as a virtue.

So freedom is under pressure from the left as well as the right, the young as well as the old. This is something new, made more complicated by our new tools of communication, the internet, on which well-designed pages of malevolent lies sit side by side with the truth, and it is difficult for many people to tell which is which; and our social media, where the idea of freedom is every day abused to permit, very often, a kind of online mob rule, which the billionaire owners of these platforms seem increasingly willing to encourage, and to profit by.

What do we do about free speech when it is so widely abused? We should still do, with renewed vigour, what we have always needed to do: to answer bad speech with better speech, to counter false narratives with better narratives, to answer hate with love, and to believe that the truth can still succeed even in an age of lies. We must defend it fiercely and define it broadly. We should of course defend speech that offends us, otherwise we are not defending free expression at all.

To quote Cavafy, “the barbarians are coming today”, and what I do know is that the answer to philistinism is art, the answer to barbarianism is civilisation, and in a culture war it may be that artists of all sorts – film-makers, actors, singers, writers – can still, together, turn the barbarians away from the gates.

On the subject of freedom, I thank all those who raised their voices in solidarity and friendship after the attack on me some 15 months ago. That support meant a great deal to me personally, and to my family, and it showed us how passionate and how widespread the belief in free speech still is, all over the world. The outrage that was expressed after the attack was in sympathy with me, but it was also, more importantly, born of people’s horror – your horror – that the core value of a free society had been so viciously and ignorantly assaulted. I am most grateful for the flood of friendship that came my way, and will do my best to continue to fight for what you all rose up to defend.

This is an edited extract from Salman Rushdie’s acceptance speech for the German peace prize awarded to him at the Frankfurt book fair last month.