Anyone not yet familiar with Maria Callas, the face, the sound and the story of the opera singer, will soon be humming the tunes. A stirring chorus of films, live shows, exhibitions, even a new museum and a hologram show, are all vying to mark the centenary of the great soprano’s birth with the loudest fanfare.

Angelina Jolie is shooting Maria, a biopic from Peaky Blinders writer Steven Knight, in which she plays the performer they once called La Divina, while in Greece, Callas’s homeland, a new museum devoted to the singer has just opened in Athens after 20 years of planning. The next few weeks also see the international publication of Diva, the new book about Callas written by British author Daisy Goodwin, and in Milan, the scene of many of the singer’s noted stage triumphs, a display of portraits opened on Thursday at the Gallerie d’Italia.

“Even someone who has never heard of Callas, if they look her up online singing the second act of Tosca, can see she was extraordinary, and not just for her singing but the way she plays the role,” said Goodwin. “Like Edith Piaf or Judy Garland, she endures because, while her voice is not syrupy, in it you can hear poignancy and meaning.”

Goodwin, who wrote the fictionalised 2016 book about Queen Victoria that altered popular assumptions about the young monarch and became the basis of a successful television series, is now determined to distinguish Callas the talent from the Callas of the newspaper headlines. It is important, she argues, that the stage performer emerges from all the myths and competing centenary stories about the star.

“She had enormous artistic courage. Watching her being interviewed, it is clear how unfiltered she was, letting her emotions show,” said the author. “I decided to write a novel because I wanted to get away from all that’s been written in biographies and look at what it took to be a singer at that level. I tried to feel my way into her head.”

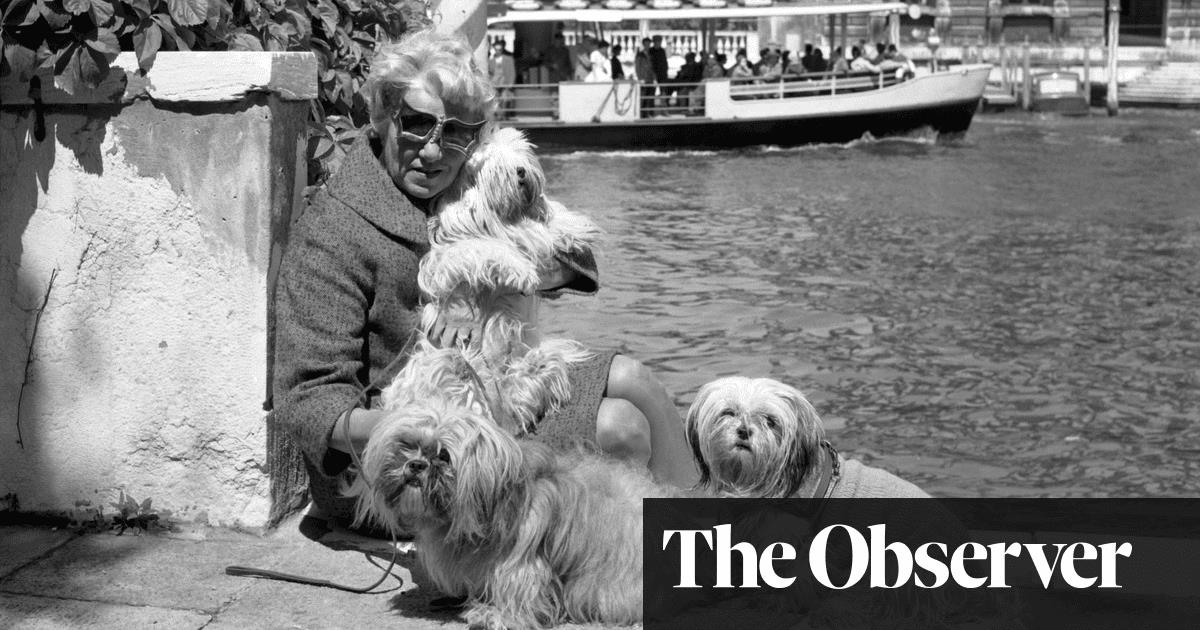

The star, who died in 1977 at 53, had a long affair with the Greek shipping magnate Aristotle Onassis, who eventually married Jacqueline Kennedy, the US president’s widow. But, more significantly in Goodwin’s view, Callas is also credited with breathing new life into a staid operatic tradition. Although her name became a byword for the jet-set lifestyle and her dramatic personal life fed gossip columns, Goodwin argues these trappings should not overshadow her artistic reputation.

“Amazingly, Callas is still Warner Classics’ best selling artist,” said Goodwin. “And the reason she’s still such an icon is that, while she is a genius of course, she transformed opera. After her, there was no more what they used to call “park and bark”, where a singer would come on stage and simply stand still. She was a great actress and because of her voice she revived a whole repertoire of bel canto operas such as Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor and Anna Bolena, each full of songs that it had been thought were too difficult.”

At London’s Royal Opera House, a recent exhibition marked the achievements of the “Covent Garden icon”, who notably starred there in Aida in 1953 and La Traviata in 1958, and earlier this month Callas fans in the capital were treated to the performance of an opera created in tribute to Callas by the artist Marina Abramović at the Coliseum, home of English National Opera.

Goodwin spoke to Abramović, 76, after watching her portrayal of the singer in 7 Deaths of Maria Callas. “I told her she was a mesmerising embodiment of Callas and she said, ‘Well, we both have a big nose, we both have bad mothers and we are both Sagittarians’.”

Goodwin suggests Jolie’s task in the same role on screen will be to convey Callas, rather than look like her: “I don’t think prosthetics would have been a great idea, but the two women do have a different kind of beauty. Callas had the sort of striking features that could be seen by the audience at the back of the stalls.”

The current V&A exhibition, Diva, features a display of costumes worn by Callas from her Covent Garden roles as Norma in 1952 and the acclaimed 1964 Tosca directed by Franco Zeffirelli. Goodwin also embraces the contentious word “diva”, which Callas did not shy away from. The singer is quoted as saying “I will always be as difficult as necessary to achieve the best.”

The word diva has heroic connotations for Goodwin, rather than simply describing a star who makes a fuss if the wrong bottled water is provided in her dressing room. Even Callas’s controversial weight loss was a demonstrative move, she argues.

“Callas was famous before she transformed herself into a woman who also looked the part,” said Goodwin. “She had to play the consumptive Violetta in La Traviata and it seems it is true she decided she wanted to look like Audrey Hepburn in Roman Holiday and so starved herself. Lots of people say that was the end of her voice, but I think she just sung too much in her 20s, performing everything from Wagner to Bellini; an extraordinary feat. For me, her short career is the true tragedy, not so much her love life.”

As a young, confident 23-year-old, Callas had turned down the offer of smaller roles at New York’s prestigious Metropolitan Opera, warning the audition panel that one day soon they would beg her to return. “And they did,” said Goodwin.

Not to be left out of the centenary, New York, the city of Callas’s birth, paid tribute to her a fortnight ago with a Teatro Grattacielo production of Spontini’s La Vestale, the opera performed by Callas at La Scala’s opening night in 1954. Meanwhile, in Paris, footage of a 1958 performance has been colourised and restored for cinematic release, and in Melbourne, Australia, next month a 3D hologram of the star will grace the stage, accompanied by a full orchestra.

But rather than relying on an artificial Callas, the real woman probably offers the best memorial. “I am not an angel and do not pretend to be. That is not one of my roles. But I am not the devil either. I am a woman and a serious artist, and I would like so to be judged,” she said.