Now that fighting has begun again, how strong is Hamas?

In military terms, Hamas is significantly weaker than it was on 7 October.

The Israeli offensive has undoubtedly damaged the group’s military infrastructure, and killed a significant number of militants. Quite how many is unclear. It is now known that Hamas needed to mobilise auxiliaries such as police into Israel for the attacks that killed 1,200 people, mostly civilians, on 7 October alongside better trained fighters, which suggests that estimates that Hamas has 30,000 or more combat troops are exaggerated.

But then Israeli claims that they have killed many thousands of Hamas militants seem high too. Senior Israeli military officers told the Guardian that Hamas casualties include dozens of battlefield commanders – which is credible – but that the senior leadership is almost untouched. “Removing Hamas from Gaza starts with the leadership of Gaza and there is a lot of work to be done,” said Eyal Hulata, a former national security adviser, on Thursday.

Hamas was also capable of firing a dozen successive barrages of rockets into southern Israel within a couple of hours on Friday morning, and many of the tunnels it has built under Gaza remain intact.

Who is in charge of Hamas?

In theory, Hamas is run by a leadership council or “shura’” drawn from regional councils elected by Hamas members in Gaza, the West Bank and by prisoners in Israeli jails. In reality, the organisation is riven by factional disputes and personality clashes.

One split divides the military from the political wings. Another pits the leaders in Gaza, who have lived for decades in the crosshairs of Israel’s security agencies or spent years in Israeli jails, against senior figures overseas in Qatar, Turkey, Lebanon or elsewhere who live in relative comfort and security.

This is aggravated by personality clashes. Yahya Sinwar, the leader of Hamas in Gaza, is said to be barely on speaking terms with Khaled Mashal, who is the best-known of the organisation’s political leaders and based in Qatar.

It is unclear if Sinwar briefed the political leadership in Qatar and Lebanon on the planned 7 October attacks but this is thought unlikely by experts – adding to the resentment.

The relatively pragmatic Ismail Haniyeh, the chair of Hamas’s political bureau, tries to mediate among the factions, though with little success, experts say.

Haniyeh also has his own job to do. “Haniyeh is leading the political battle for Hamas with Arab governments,” said Adeeb Ziadeh, a specialist in Palestinian affairs at Qatar University. “He is the political and diplomatic front of Hamas.”

The internal disputes complicate this task. In recent weeks, Haniyeh has moved between Turkey and Qatar’s capital, Doha, escaping the travel restrictions of the blockaded Gaza Strip and enabling him to act as a negotiator in the earlier ceasefire deal or talk to Hamas’s main ally, Iran.

But the final yes or no comes from Sinwar. When during recent talks Sinwar decided to cut off communications, negotiations stalled. “This pretty effectively underlined who is calling the shots,” said one European diplomatic source briefed the negotiations.

Is Hamas still in control in Gaza?

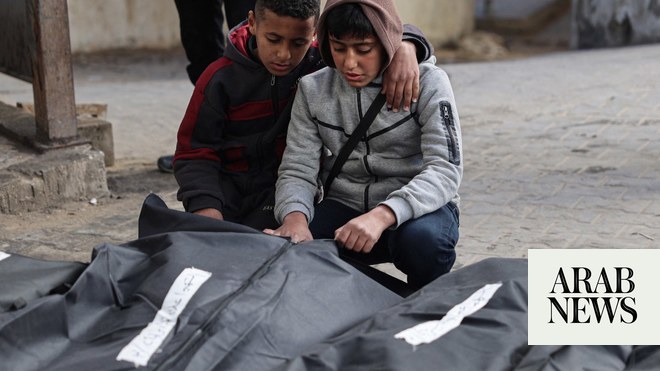

Civil administration has broken down across all of Gaza, where 15,000 people, 40% of whom were children, were killed in the five weeks of the Israeli offensive, according to local authorities, at least 1.5 million are displaced and huge swaths of urban areas have been reduced to rubble. The Israel Defense Forces has taken over the north of Gaza, where most government offices were, but elsewhere Hamas still appears in charge of the territory it has ruled for 16 years. Hamas was able to locate, gather and return dozens of hostages to Israel, despite some being held by smaller independent factions or criminal clans. It also managed the optics of the release effectively and so scored a major propaganda coup.

What’s happening in the occupied West Bank?

Hamas was already popular in the West Bank, something that most analysts attribute more to the failures of the Palestinian Authority than the Islamist organisation’s ideological appeal. A poll in September suggested that Haniyeh, who left Gaza in 2016, would win in presidential elections against Mahmoud Abbas, the Palestinian president, but would lose against a stronger candidate.

The violence in Gaza has raised tensions in the West Bank, where nearly 240 Palestinians have been killed by Israeli soldiers or settlers since 7 October, according to the Ramallah-based Palestinian health ministry, and the release of many prisoners from Israeli jails has given Hamas a huge boost. Many residents of Ramallah, a town supposedly a stronghold for the ruling party, Fatah, have expressed their admiration for Hamas. At one rally this month, members of liberal political parties and organisations chanted pro-Hamas chants.

The shooting attack in Jerusalem on Thursday claimed by Hamas, which killed three people at a bus stop, may have been a spoiler aimed at derailing any extension to the ceasefire, a threat of what could follow if fighting was renewed, or simply a pressure valve to placate local militants opposed to any deals.

A Hamas statement after the attack quoting the Qur’an spoke of “a jihad of victory or martyrdom”, language that has been absent recently from Hamas public statements.

Could there be a new ceasefire?

The first phase of this conflict is over, analysts say. The arrangement reached on 24 November, which brought a temporary halt to fighting in Gaza and allowed for women and children held as hostages in the Strip to be freed in exchange for Palestinian women and children held in prison by Israel, cannot be renewed but will have to be replaced by a new deal.

Any fresh deal would involve the exchange of individuals who are much more valuable, in the brutally cynical language of such negotiations, to both sides. Israel will want freedom for male civilians among the hostages and also the soldiers that Hamas is holding. Hamas will want more senior prisoners released, including some that Israel will absolutely not want to free, and possibly in much greater numbers. Ezaat Al Rashq, a Hamas leader, told Qatar’s Al Araby TV last week: “We are willing to negotiate over [Israeli] military prisoners but at the right time and the price will be much higher than the price of releasing other hostages.”

All negotiations are a test of strength. Between such bitter enemies, with both sides committed to a lengthy conflict and a total absence of trust, this is particularly true. Israeli policymakers believe that military pressure will force Hamas to make concessions. Hamas believes it can turn Israel’s great military strength into a political weakness, losing a battle but winning the war. The tragic reality is that violence is now an extension of negotiations, and the negotiations part of the violence.