When Toumi Djaïdja, a 20-year-old youth worker, was shot by police as he helped a teenager who had been bitten by a dog, he did not know it would change the course of French history.

It was 1983, when France was plagued by numerous racist murders of people of north African background, amid anger on housing estates and allegations of police violence. Already, Djaïdja, from an Algerian family on the Minguettes housing estate in Vénissieux outside Lyon, had held a sit-in and a hunger-strike for equal rights and an end to clashes between police and youths.

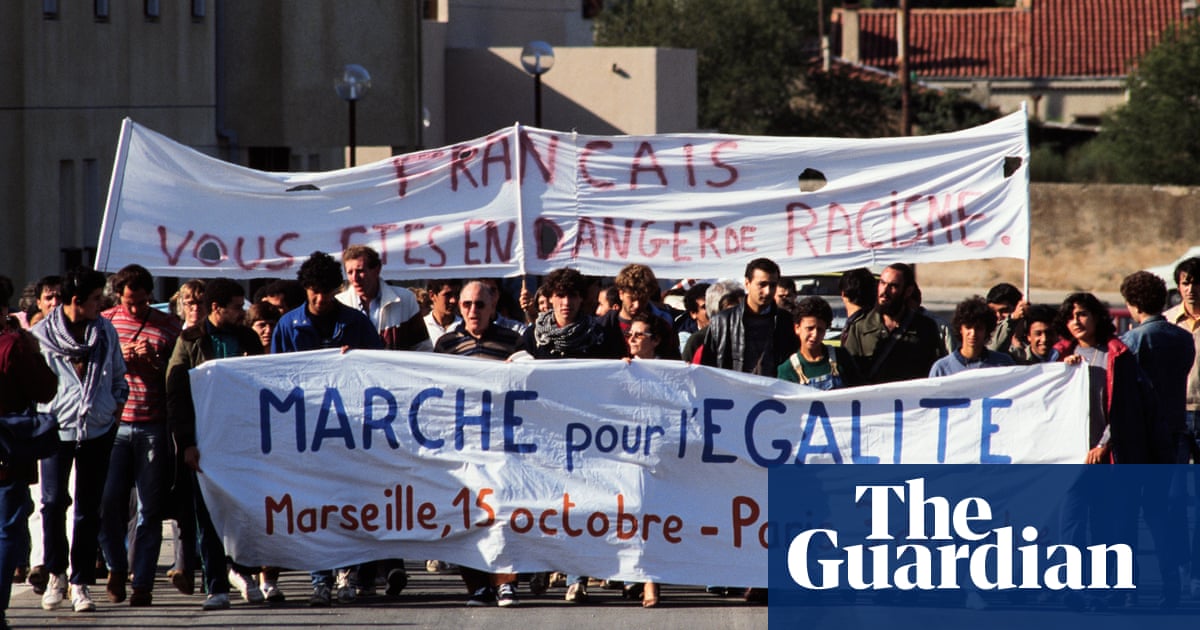

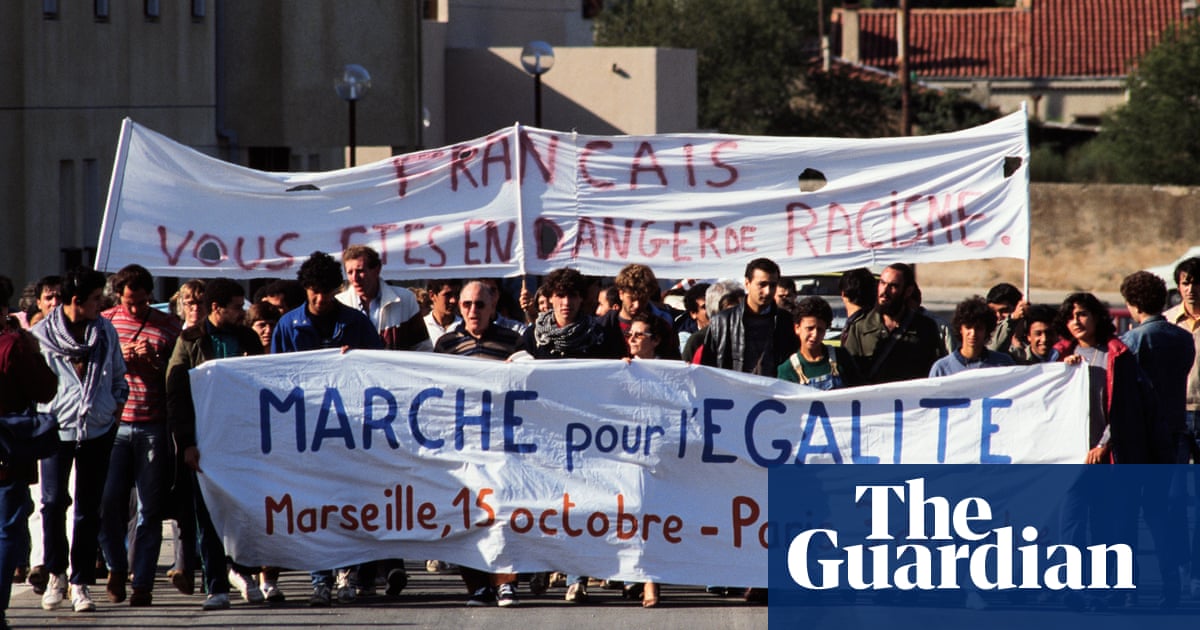

Waking from a coma after the police bullet nearly killed him, he asked friends from the estate to join him in a peaceful “march for equality and against racism” from Marseille to Paris. The idea was to travel through villages and towns to foster nonviolence and end the mood of fear. Twelve of them set off, but the crowd had swelled to more than 100,000 by the time they reached Paris, where Djaïdja and some fellow marchers were invited to the Elysée by the Socialist president François Mitterrand.

This week, France is marks the 40th anniversary of its first nationwide anti-racism march. But, amid the concerts, murals, museum events and discussions comparing the initiative to the nonviolence of Martin Luther King, there is a sense of urgency.

Academics and historians are warning that this key moment in the history of French race relations and grassroots citizen activism must be taught in schools, better commemorated and written into the nation’s narrative, or risk being overshadowed by today’s divisive politics.

Five months ago France experienced widespread protests and unrest over the police shooting of Nahel, a 17-year-old boy of Algerian descent, at a traffic stop outside Paris in June, and the country has been shocked more recently by far-right street marches. A political row over Emmanuel Macron’s new law on immigration has intensified.

Against this fraught backdrop, say historians, the peaceful 1983 march should be celebrated as an antidote to divisions in French society.

“The march was about bringing people together, finding unity and peace, and not dividing people – that message is fundamental today,” said Djaïdja, who now gives talks to teenagers across France. “Not all young people today even know about the march – it’s crucial that it’s given its place in wider French history and collective memory.”

The early 1980s in France were marked by extreme racist violence, where people of north African origin – Algerian, Moroccan or Tunisian – were shot dead on the street. Toufik Ouanès, a nine-year-old of Algerian heritage, was shot dead in La Courneuve, north of Paris, as he let off firecrackers for Bastille Day, which a neighbour complained were too loud.

Even as the equality march was under way, France was horrified by a racist murder on a train from Bordeaux to Ventimiglia, when a 26-year-old Algerian man, Habib Grimzi, was attacked by a group of men who had applied to join the French foreign legion. They beat him, while no other passengers protested, and then killed him by throwing him from the moving train.

“I could put people in a cold sweat with the details of what it was like in the early 1980s, but I prefer a message of optimism when I meet teenagers today,” Djaïdja said. “I received hundreds of letters during the march and only six were racist. In the countryside and villages, there was a great welcome … you realise something that is true today: in reality, the drive to live together peacefully is stronger than what pulls us apart.”

But when Djaïdja meets young people on housing estates today with his message of nonviolence and acceptance, many complain of a lack of justice. They think they will not get fair treatment from police, or will be singled out for their colour.

It is something Djaïdja understands. A year after the march, he was arrested and jailed for allegedly taking part in a violent robbery; his fingerprint had allegedly been found on a car. He denied all charges and appealed, but was given a heavier sentence on appeal. He was released after a presidential pardon from Mitterrand.

For Djaïdja, the recognition of a miscarriage of justice would have been preferable to a presidential pardon. When he was shot by police in 1983 as he went to help a teenager on his estate, there was never a court case and he never got justice, he said.

Djaïdja said that after Nahel’s killing in June and unrest on housing estates, it was important that people were given confidence in the justice system or it would feel like history was repeating itself.

“There has to be a clear message to young people that whatever the colour of your skin, your origins or background, there is justice in France. Young people often tell me ‘It’s all very well you talking of peace and harmony, but something happened to me and there is no justice’. People have to know that justice is for everyone.”

Despite Djaïdja’s declaration as the march arrived in Paris – “Bonjour France of every colour!” – some media called the movement the “march of the Beurs” – using a slang term for Arab or people of north African heritage, a label activists rejected.

France’s recently reopened Museum of the History of Immigration focuses on the year 1983 in its new permanent exhibition, referencing not only the march, but also the first significant electoral gains of Jean-Marie Le Pen’s far-right Front National. The museum, which will host a commemoration of the march on Friday, has launched an initiative across France to gather historical objects from the march, such as banners and photographs, and to interview marchers.

“This is part of writing this story into French collective memory in a bigger way,” said Constance Rivière, who heads the museum. “If we can’t tell our story in all its components, there will still be a feeling that history isn’t a common account, it doesn’t belong to us, it’s imposed from on high.”

Naïma Huber-Yahi, a historian at the Côte d’Azur University and head of the Pangée Network association for cultural diversity, said the march had had a massive impact on France. First it opened up the debate on racist violence and murders, which decreased in subsequent years “although they did not stop entirely”, she said. It also saw a boom in art and culture by people of north African heritage, such as the film-makers Rachid Bouchareb and Mehdi Charef.

But, she said, politically, “the change promised by the left didn’t happen. The situation got worse in working-class neighbourhoods.” Nor did political parties on the left promote minorities to their highest ranks – that happened decades later and began on the right.

Huber-Yahi believes it is crucial now to include the march in national history curriculums at school as evidence of the positive impact of citizen engagement on working-class housing estates in the banlieue.

“If we don’t celebrate, recount, analyse and pass on these moments then people will still be seen as outsiders in their own nation … France will never be able to understand the way that identity politics still structures its politics if it can’t look at itself in the mirror: it’s multicultural, multi-ethnic, marked by the history of colonial events and slavery, that it has not yet been able to recount and pass on.”