People of Palestine were denied the benefit of US President Woodrow Wilson’s post-war doctrine of the “self-determination of peoples”

Between 1919 and 1948, at least nine official reports issued warnings about the consequences of “the Jewish colonization of Palestine”

LONDON: Between 1919 and 1948, at least nine official reports commissioned by the British and US governments issued a series of dire warnings about the consequences of the Jewish colonization of Palestine.

But in the headlong rush to accommodate the aims of the Zionist movement, born in Eastern Europe in the late 19th century, all these warnings were brushed aside.

Seventy-five years after the foundation of Israel, the causes of the seemingly insoluble Arab-Israeli conflict and the origins of the current crisis in Gaza can be found in prophetic words written up to a century ago.

In 1922, Palestine was one of several former Ottoman territories placed by the League of Nations under temporary mandates to be administered by France and Great Britain in preparation for them to become independent nations.

In due course Iraq obtained its independence in 1932, followed by Lebanon in 1943, Syria in 1944, and the Kingdom of Jordan in 1946.

The people of Palestine, however, were to be denied the benefit of US President Woodrow Wilson’s post-war doctrine of the “self-determination of peoples.”

In December 1917, the British government, at war with Germany, and anxious to secure the support of America and international Jewish opinion, had publicly proclaimed its backing for the “establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people.”

One of the foremost opponents of the declaration by Lord Balfour, Britain’s foreign secretary, seen by many as a betrayal of earlier pledges of independence made to the Arabs, was Sir Edwin Montagu, secretary of state for India and the only Jewish member of the Cabinet.

Like many non-Zionist Jews, he held that Judaism was a faith, not a nationality, and feared the creation of a “national home of the Jewish people” would mean Muslims and Christians “are to make way for the Jews, that the Jews should be put in all positions of preference,” and that the Arabs would become foreigners in their own land.

Regardless, in April 1918, the British government gave its blessing to a Zionist Commission to Palestine, led by Chaim Weizmann, the leader of the British Zionist Federation and the future first president of Israel.

In a memo to the Foreign Office, Col. Ronald Storrs, the British military governor of Palestine, warned that the commission lacked “a sense of the dramatic actuality,” and that the Zionist project “can hardly open for the inhabitants the beatific vision of a new heaven and a new earth.”

The commission’s report formed the basis of the Zionist movement’s presentation to the post-war Paris Peace Conference in 1919, to which no Arab representatives from Palestine were invited, but at which the former territories of the Ottoman Empire were carved up between the victorious allies.

After reading the Zionist delegation’s proposals that the conference should “recognize the historic title of the Jewish people to Palestine,” Lord Curzon, Britain’s then-foreign secretary, wrote to his predecessor Balfour to express his alarm.

Weizmann, he believed, “contemplates a Jewish State (with) a subordinate population of Arabs, etc. ruled by Jews; the Jews in possession of the fat of the land, and directing the Administration ... with the Arabs as hewers of wood and drawers of water.”

Although “the poor Arabs” formed the vast majority of the population of Palestine, they were “only allowed to look through the keyhole” while the Zionists planned “a practically complete dispossession of the present non-Jewish inhabitants of Palestine.”

President Wilson, reminding his wartime allies that “one of the fundamental principles to which the USA adhered was the consent of the governed,” dispatched a commission to Palestine.

Reporting in 1922, the King-Crane Commission recommended “serious modification of the extreme Zionist program for Palestine of unlimited immigration of Jews.”

It added: “The non-Jewish population of Palestine — nearly nine-tenths of the whole — are emphatically against the entire Zionist program … To subject a people so minded to unlimited Jewish immigration, and to steady financial and social pressure to surrender the land, would be a gross violation of (their) rights.”

Yet the commission’s recommendations, and the rights of the Palestinians, were ignored.

In the so-called Churchill Memorandum, issued in July 1922, the British government declared that the Jewish people were in Palestine “as of right and not on sufferance,” and that in pursuit of the goal of establishing a Jewish national home in Palestine “it is necessary that the Jewish community in Palestine should be able to increase its numbers by immigration.”

Alarmed, Palestinian representatives wrote to British administrators to make the case for a role in their own future, and for “the immediate creation of a national government which shall be responsible to a parliament of all, whose members are elected by the people of the country — Muslims, Christians and Jews.”

The alternative, they warned, was “division and tension between Arabs and Zionists increasing day by day and resulting in general retrogression.”

But, again, the warning went unheeded.

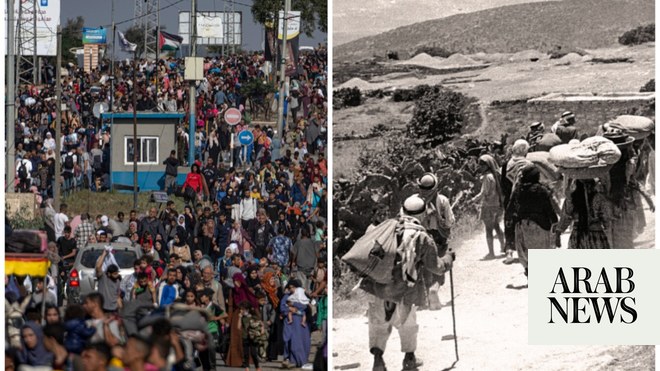

In the decade from 1920 to 1929, about 100,000 Jewish immigrants came to Palestine, doubling the Jewish population in a country with a total population in 1922 of about 750,000, of whom almost 600,000 were Muslims.

In August 1929, tensions created not only by the rising tide of immigration, but also by the anti-Arab policies of Jewish organizations spilled over into outbreaks of intercommunal violence that left hundreds of Jews and Arabs dead, and many injured.

In 1930 the Shaw Commission, appointed by the British government to investigate the troubles, concluded that the fundamental cause was “the Arab feeling of animosity and hostility toward the Jews consequent upon the disappointment of their political and national aspirations and fear for their economic future.”

Immigration to Palestine, the commission found, was in effect under the control of the Zionist General Federation of Jewish Labor, which selected only Jews for admission.

This policy of racial discrimination also extended to the recruitment of only Jewish labor to work on the Jewish farms and settlements that were springing up on land bought by well-funded international Jewish organizations.

The “persistent and deliberate boycott of Arab labor,” the commission concluded, was “a constant and increasing source of danger to the country.”

Consequently, in October 1930, Lord Passfield, the British secretary of state for the colonies, announced plans to reclaim authority from the Jewish Agency over the issues of immigration and land purchase.

But that policy, designed to both appease and improve the lot of the Arabs in Palestine, was short-lived. It was countermanded the following year by an extraordinary letter from British Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald to Chaim Weizmann, read out in the House of Commons on Feb. 13, 1931.

MacDonald reassured Weizmann that “the obligation to facilitate Jewish immigration and to encourage close settlement by Jews on the land remains a positive obligation of the Mandate.”

As the exhaustive UN document “Origins and Evolution of the Palestine Problem” notes, “this sudden reversal of British policy, coming as it did after Palestinian hopes for fair play had been raised by the Passfield White Paper, did little to improve the deteriorating situation in Palestine.”

International events, in the shape of the rise of the antisemitic Nazi party in Germany, then conspired to make matters even worse. During the 1930s a quarter of a million Jews emigrated to Palestine, with 134,000 arriving between 1933, the year Adolf Hitler took power, and 1936.

More violence between the two communities exploded in 1933 and, although the causes were blindingly obvious, yet another British commission was appointed in 1937 to find out why.

The Peel Commission concluded that the Arab reaction to the “sudden and striking” increase in Jewish immigration was “quite natural. All that the Arab leaders had felt in 1929 they now felt more bitterly … the greater the Jewish inflow, the greater the obstacle to their attainment of national independence.”

Recognizing that reconciling the statehood ambitions of the Jews and the demands of the Palestinians to independence was not possible under the Mandate, the commission raised the prospect of partition, which “seems to offer at least a chance of ultimate peace.”

But the proposal was rejected by both the Arab Higher Committee, determined to achieve the promised full independence for Palestine, and the 1937 Zionist Congress, determined to transform the whole of Palestine into a Jewish state.

After the failure of a conference in London in 1939 on the eve of the Second World War, attended by the Jewish Agency and representatives of the Palestinians and the Arab states of Egypt, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, Transjordan and Yemen, Britain made one more attempt to unravel the Gordian knot it had created.

In May 1939, Malcolm MacDonald, the British colonial secretary, issued a white paper that would be the British government’s last statement of policy on Palestine.

This rejected the idea of partition, or the creation of either a Jewish or Arab state, proposing instead to strictly restrict Jewish immigration and land acquisition, and “the establishment within 10 years of an independent Palestine State ... in which Arabs and Jews share in government.”

Although the coming of the war put consideration of such plans on hold, even as Britain was battling the Nazi regime responsible for instigating the Holocaust, militant Jewish groups began a campaign of terror in Palestine.

Throughout the war years, groups such as the Stern Gang, the Irgun and the Haganah — all of which would merge in 1948 to form the Israel Defense Forces — attacked British targets, carrying out political assassinations, kidnappings and acts of terrorism.

The most serious of these included the bombing of the offices of the British Government Secretariat in the King David Hotel in Jerusalem in July 1946, which killed more than 80 Arab, Jewish and British civil servants, and the assassination by the Stern Gang of Lord Moyne, the British minister for the Middle East, in Cairo in 1944.

Despite the public condemnation of the acts of “a new set of gangsters worthy of Nazi Germany” by British wartime leader Winston Churchill, a long-time supporter of Zionism, the Zionists would soon get their way.

Following the failure of another conference in London, in February 1947 the British finally gave up, relinquished the mandate for Palestine, and handed the problem they had created to the fledgling UN.

The UN proposed the partition of Palestine into two independent states, with the city of Jerusalem, so important to all three Abrahamic faiths, to be administered by a “Special International Regime.”

Although the Arabs still outnumbered the Jews two to one, the plan allocated 56 percent of the territory to the Zionists and was rejected by the Arab Higher Committee, the Arab League and Arab governments throughout the region.

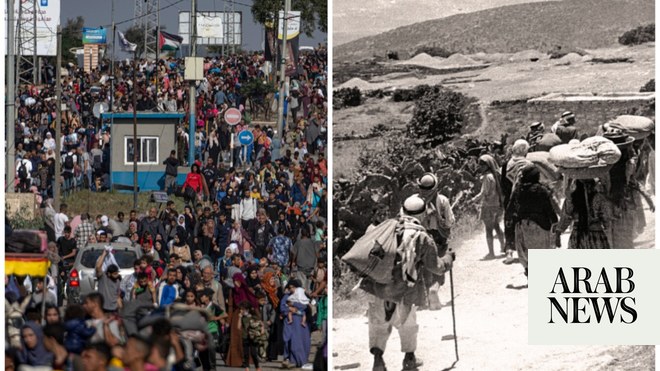

Following the adoption of Resolution 181 by the UN General Assembly on Nov. 29, 1947, and the announcement by Britain two weeks later that it would end its mandate on May 15 the following year, Palestine descended into civil war.

On May 14, 1948, David Ben-Gurion, head of the Jewish Agency, declared the establishment of the State of Israel, and the stage was set for 75 years of strife and oppression, of which the events on and after Oct. 7, 2023, are merely the latest manifestation.

Writing in 1968, the British historian Arnold J. Toynbee, who had attended the 1919 Paris Peace Conference as a British delegate, passed a judgment on the tragedy of Palestine that holds true to this day.

“The reason why the State of Israel exists today … is that, for 30 years, Jewish immigration was imposed on the Palestinian Arabs by British military power,” he wrote.

“If Palestine had ... become an independent Arab state in 1918, Jewish immigrants would never have been admitted into Palestine in large enough numbers to enable them to overwhelm the Palestinian Arabs in this Arab people’s own country.”

The tragedy in Palestine, he concluded, “is not just a local one; it is a tragedy for the world, because it is an injustice that is a menace to the world’s peace.”