It was a week before Christmas last year when Serhiy Sydorenko underwent corneal surgery on his right eye, a complicated operation that, if successful, would put an end to more than three decades of blindness for the 56-year-old Ukrainian.

When the nurses first removed the bandages some hours after the operation, all he could see was light. Painfully bright light, as though someone was directing a beam right at his face. The nurses applied eyedrops and re-tied the bandages.

A few hours later they removed them again and Serhiy could make out the blurry outline of a nurse’s face looking at him through the bright glare. The next morning, the professor who had operated on him paid a visit and the bandages came off once more.

Serhiy sat up in bed and looked around the room. He saw the professor, and for the first time in their long marriage he saw his wife, Tamara. Overwhelmed with emotion, he repeated a single phrase: “I can see!”

It was a moment he had been dreaming of for 36 years.

Serhiy lost his vision in an accident during his military training in the Soviet army in 1986. He married Tamara in 1991; later, he became a successful judo athlete, winning Paralympic bronze in 2008.

All those years, Serhiy felt loved and supported, but also that something was missing from his life. When he travelled the globe for judo, he did not see the places he was visiting; he and Tamara raised a son and a daughter to adulthood, but he had never seen their faces.

When Russia launched its full-scale war on Ukraine last year, the couple left their home town of Zhytomyr, west of Kyiv, and moved to the Polish city of Poznań with their daughter, Margarita. There, Serhiy heard about a professor who performed corneal transplants in Katowice. In mid-December, he went under the knife.

After several days of rest in hospital, Serhiy was discharged on the morning of 24 December with the vision in his right eye fully restored.

As he and his wife made their way from the hospital to the train station, Tamara tugged at him to hurry up so they wouldn’t miss the train. But all kinds of things were now catching Serhiy’s newly functioning eye.

When a woman walked past with a tiny, fluffy dog on a leash, he stopped in his tracks. He remembered sheepdogs from his Soviet youth but did not know people kept miniature dogs that looked like toys. He was fascinated by the way people dressed, by the buildings and by what cars looked like in 2022. The last time he could see, most of the cars had been Ladas.

The couple caught the train and made it to Poznań after darkness had fallen. In Poland, the main festive celebration takes place at dinner time on Christmas Eve, and when they got home the Christmas table was already set, heaving with various dishes of salads, fish and meat prepared by Marta, the Polish woman who hosted them in her flat. Also present was Margarita. Serhiy looked at his daughter and for the first time he saw her.

“It was a Christmas miracle,” he says, remembering the dinner nearly a year later.

Serhiy and Tamara still live in Poznań; they arrive together to our interview at a cafe in the city. Serhiy wears sunglasses; he still needs them when there is bright light. Over the next four hours, with brief pauses once an hour to apply eye drops, Serhiy tells his life story.

Born in Zhytomyr into a Soviet military family, Serhiy was a sporty child, taking up judo at school, and he dreamed of becoming an army officer. At 18, he entered military college; while there, an incident left him blind. He refuses to talk about it. “These things are better to forget than to remember, that’s how I’ve coped,” he says.

Even his doctors never found exactly what happened, only that an explosion left him without sight. From his left eye he could make out changes in light, and sometimes see blurry shadows. From his right eye, nothing.

The first years after the injury were immensely difficult. Serhiy was decommissioned, and felt as if all the grand plans he had made for his life had been snatched away. He needed help to perform simple tasks. He developed insomnia, and fell into depressive periods. It’s something he thinks a lot about now, as thousands of Ukrainian soldiers come back from the frontlines with serious injuries. “They will need really good moral and psychological support,” he says.

He credits his parents with keeping him from going under and ensuring he did not turn to alcohol to cope. He began working odd jobs at a sports academy in Zhytomyr, where Tamara was a student. She liked the fact he wasn’t a drinker, and at a summer picnic the pair got chatting. Soon, they began dating; they married in 1991, the same year Ukraine became independent.

A local judo coach told Serhiy about Paralympic judo and suggested he take up his childhood passion again. “We lived near the stadium and I went there to train, Tamara took me there. I had three training sessions a day, so I didn’t have time to get depressed,” Serhiy recalls. He tried to pitch in as much as he could with housework, though he concedes he “smashed up a whole kitchen’s worth of crockery” while trying to help with the washing up.

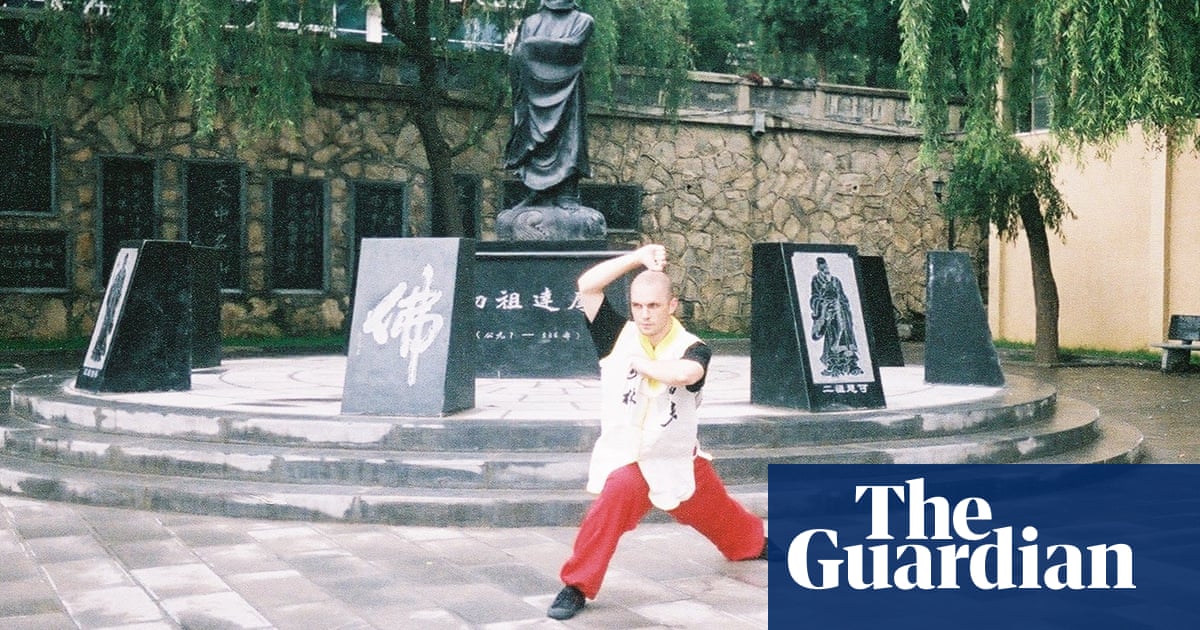

By 1996, he was training with the Ukrainian national judo team and had begun travelling to international competitions, competing in the 66kg weight category and later moving up to 73kg. His signature move was the windmill, in which the judoist hauls their opponent into a fireman’s lift and then tosses them to the ground. He came fourth in the Paralympics in 2000 and 2004 and went one better in 2008, winning bronze.

The other big moment in his career was his 2003 victory over a British judoist, Simon Jackson, to win the world championship of the International Blind Sports Federation in Quebec. “Jackson would come out like Mike Tyson with all his trainers and massagers … the whole hall was calling out ‘Jackson! Jackson!’. He’d won four Paralympic golds, but I managed to do him with the windmill,” Serhiy says, visibly animated by the memory.

Judo helped Serhiy cope physically and psychologically with his lack of sight. It taught him how to fall safely, a useful skill in his circumstances, and also helped to overcome a feeling of vulnerability, one of the most difficult effects of blindness.

“There was one time when me and my wife were walking and a guy was standing in our way, a big guy who had been drinking. He didn’t want to let us pass and he shoved Tamara. I went for him and he went flying on to the asphalt,” Serhiy recalls with a chuckle. The man looked up at his diminutive assailant holding a white cane and wondered what on earth had just happened.

Serhiy knew there was a theoretical chance of an operation to restore his sight, but it was not available in Ukraine. Then came the Russian invasion. He did not want to leave home, but his daughter was terrified by the air raid sirens, and the family decided to travel to Poland for a while. It was a decision that eventually led to Serhiy getting his sight back.

The cornea is a clear, dome-shaped membrane. It protects the rest of the eye, and needs to be transparent so that light rays can penetrate it and hit the retina. If the cornea loses this transparency, a person can no longer see.

In Serhiy’s case, the heat and chemicals in the explosion had caused massive inflammation, with a thick layer of blood vessels forming on his cornea. “When I first examined his eyes, I saw a pair of heavy curtains,” says Prof Edward Wylęgała, in a telephone interview from Katowice.

Wylęgała, the head of the ophthalmology clinic at the Medical University of Silesia, immediately felt that Serhiy would benefit from an implant of the Boston artificial cornea. Developed in the 1960s by Claes Dohlman, an ophthalmologist at Harvard Medical School, the Boston cornea was approved by the FDA in the US in 1992 and provides an alternative for patients not amenable to standard cornea transplants.

Dohlman, now 102, has refused to sell his idea for commercial purposes, and the teaching hospital of Harvard Medical School remains the sole manufacturer of the Boston cornea. In 2010, after years of persuasion, Wylęgała convinced Dohlman to donate five of the devices to his hospital, and with his team he performed the first surgeries in Poland, all successful. Now, about 100 operations a year are done in Poland using the Boston cornea.

More than 12 million people globally are in need of a corneal transplant, according to a 2015 survey. Most will not receive one. “I can only imagine how many potential candidates for this kind of surgery we would have in countries like India or China,” says Wylęgała.

Before the operation, Serhiy had a feeling that he remembered well from his judo days – the stomach-churning nerves, the anticipation, the agony of the wait. Wylęgała came to the room and gave him a hug; the nurses stroked his hair and joked around to calm him down.

The operation involved the prosthetic cornea and donor tissue taken from the eye of a recently deceased person. Wylęgała compares the preparatory work to putting together tiny Lego blocks under a microscope. “It’s crucial to have a gentle hand because our operating field measures about one square centimetre,” he says. “The eyeball … weighs only 7 grams. But that’s all it takes to see the world.”

After the operation was completed, Wylęgała had trouble sleeping, and he rushed to the hospital early the next morning to see how the patient was doing. Even for someone with a long career of restoring people’s sight, being in the room when Serhiy saw his wife for the first time was a special moment.

“Whenever someone asks me about this case, it’s not the surgery that comes to my mind but this very moment,” he says.

Serhiy is still a little lost for words to describe what those first moments of sight were like. Perhaps there simply aren’t adequate words to describe such a moment. “I just kept thinking: has the miracle really happened?” he says.

Since the operation, everything has acquired a new visual dimension. In May, Serhiy and Tamara travelled back to Zhytomyr for a few days, to visit his ageing mother, his son and his younger brother, who is fighting in the Ukrainian army. The visit coincided with Russian missile attacks on the city, making it a bittersweet return. But there was a chance to see many old friends. “In my head, I had imagined them how they looked in childhood, but of course they look nothing like that now. I don’t think I would have recognised any of them on the street,” he says.

The other person he struggles to recognise is himself. When he looks in the mirror, he sees the storied face of a 56-year-old man looking back at him. The last time he looked, it was a 19-year-old.

He’s also going back over old memories and adding visuals. Watching videos of his old judo bouts is a favourite pastime. He can now make his way around Poznań alone, without help. So far, he and Tamara seem to be coping well with the dramatic change in their dynamic. “Life is easier for me now,” she concedes.

This Christmas Eve, the family will again sit down with their Polish host Marta in Poznań. Serhiy hopes that soon he will receive a second operation, to restore sight in his left eye as well. In the meantime, he is still finding new things to be amazed by. He recently took a short trip to Sopot, on Poland’s Baltic Sea coast, and was overwhelmed by the sight of the sea. He had swum in the ocean in Brazil and Australia, but without seeing the water. And the mundane discoveries can sometimes be just as inspiring as the sublime ones. “Before, a soup was a soup for me. Borscht was borscht. And now I’m looking and I can see this tiny carrot is swimming in it! Everything feels so different,” he says.

Some mornings, he wakes with a start, wondering if he has imagined the whole thing. He quickly raises his right hand, where he has a large birthmark that his daughter likes to rub for good luck. When he looks at the birthmark, he relaxes. He can still see. “It’s still a surprise for me every day,” he says.