One year ago today, Rishi Sunak made five pledges that he said were a straightforward yardstick for his government’s success: “No tricks. No ambiguity. We’re either delivering for you or we’re not.” Here’s a report card on progress so far, with analysis from the Guardian’s in-house experts.

Pledge: Halve inflation from 10.7% by the end of 2023

When Sunak made his speech, inflation was already forecast to meet this target. At various points in the year, though, it looked touch and go: by October, inflation remained at 6.7%, largely because of soaring fuel costs. But it has since dropped to 3.9%. So the target has been met, barring an unlikely spike when the last 2023 figures are released in two weeks.

What did Sunak have to do with it? Not much, says Nils Pratley, the Guardian’s financial editor. “The job of fighting inflation belongs primarily to the Bank of England. International energy prices – no longer rising – also played a big role.” It’s also important to remember that a declining inflation rate means that prices are going up more slowly, not coming down. With wage growth slowing, that has not yet translated to a big dividend for voters.

This year, “expect the rate to fall even closer to the Bank’s target of 2%”, Nils adds. “Despite the central bank’s cautious warnings about the potential stickiness of inflation, financial markets currently expect Threadneedle Street to have room to cut interest rates from 5.25% to 4% during the course of 2024. That is useful for a governing party in an election year. It does not mean, however, that voters will forget the two-year squeeze on living standards.”

Verdict: Success (though not necessarily Sunak’s)

Pledge: Grow the economy

This is a modest target: 0.1% gross domestic product (GDP) growth each year would be enough to meet it, and that is not an outcome most economists would view as a success story. In the event, while final figures are not available until February, Goldman Sachs and JP Morgan both say that they expect 0.5% growth over the whole year. But GDP fell by 0.1% in the third quarter and may have done so again between October and December, which would mean the UK is in recession.

In 2024, says the economics correspondent Richard Partington, “Sunak is facing the prospect of a fairly bleak year for economic growth. The Bank of England has warned that Britain has a 50-50 chance of a recession this year, while the government’s own independent forecaster, the Office for Budget Responsibility, isn’t much more optimistic: it’s forecasting growth of just 0.7% for 2024 as a whole, less than half the average rate recorded in the years running up to the 2008 financial crisis.”

Verdict: Technical success against a low bar

Pledge: Get national debt falling

So far, and despite Rishi Sunak’s repeated claims to the contrary, this hasn’t happened. Debt stood at 88% of GDP in November, compared with 85% at the end of 2022. So how did Sunak justify his claims? Downing Street says they are based on a promise that net debt will be falling as a proportion of GDP by the final year of the five-year forecast, in 2027-28.

The senior economics commentator Aditya Chakrabortty is unimpressed, and has a helpful image to explain. “Analysis of public sector net debt can be a tad heavy for the first week of January, so let me clothe this question in something rather more seasonal,” he writes. “If someone told you they were truly, definitely going to lose a tonne of weight in a year and they’d do it all in the party month of December, you might well do a massive chinny reckon (or whatever it is the young people do to signify doubt these days). But that is pretty much how Rishi Sunak plans to meet this pledge.

“On the state’s own forecasts, debt will keep on going up until April 2028. But relax! Sunak and Jeremy Hunt will truly, definitely start getting it down then, by making spending cuts so sharp that hardly anyone believes they will happen. As a strategy, it makes your mate’s diet plan look positively plausible.”

Verdict: Failing

Pledge: Bring NHS waiting lists down

Not happening: the waiting list has gone from 7.2 million when Sunak made his speech to 7.7 million in October, the most recent figures available.

“Sunak has sought to blame ongoing industrial action for his failure to cut waiting lists,” writes the Guardian’s health editor, Andrew Gregory. “Some of the public may sympathise with that argument. However, analysis by the Health Foundation, an independent thinktank, shows that strikes by doctors had so far lengthened the waiting list by about 210,000.” Even without that 210,000, the number would still be going up.

The same analysis predicted that the number of patients on waiting lists could hit 8 million by this summer, and “the prospect of the waiting list dipping below 7.2 million before the next election looks increasingly unlikely”, Andrew says. “Expect Sunak to squirm and pivot with bold new claims of progress.

“His go-to at the moment? A focus on 18-month waits. They are down by about 90% since their peak in September 2021, which is not to be sniffed at. The prime minister knows he can’t hide from the big numbers, though. And the fact they have gone up, not down, since he promised to reduce them is all that matters.”

Verdict: Failing

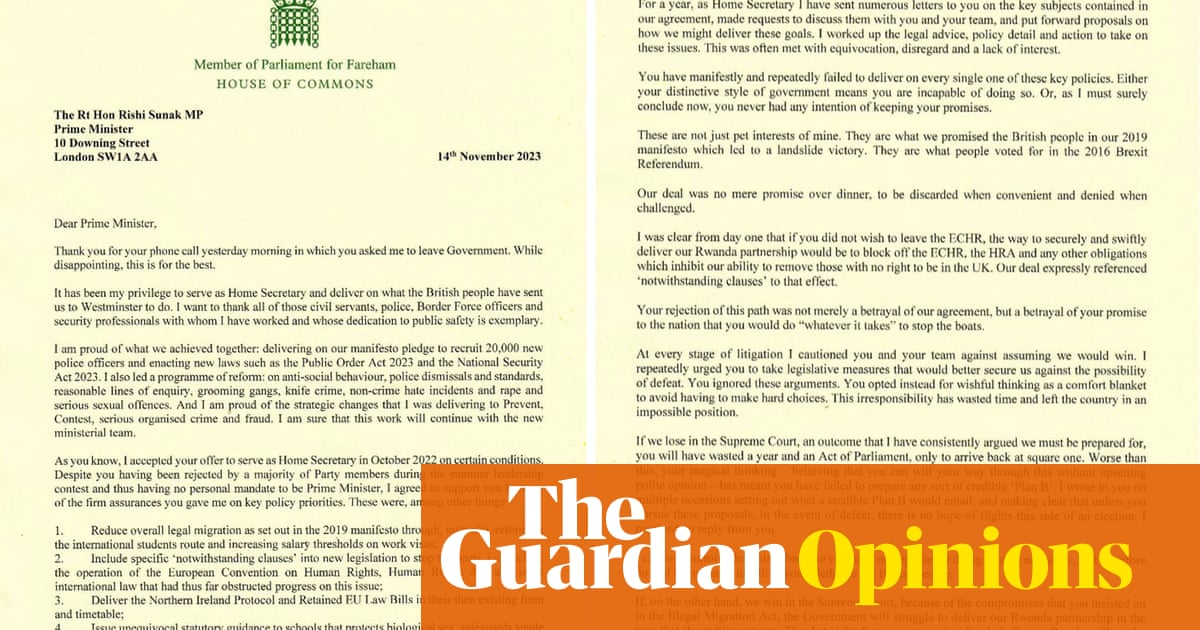

Pledge: ‘Stop the boats’

Initially, this was followed by a technical qualifier: after promising to “stop the boats”, Sunak said that he would “pass new laws to stop small boats”, a much lighter commitment. Since then, Sunak has leaned in to the simpler – and harder – version.

There is confusion over the deadline. This week, the home secretary, James Cleverly, told LBC that his “unambiguous” target was “to reduce it to zero” by the end of 2024. But then the prime minister’s spokesperson said that Sunak “would not set a deadline”.

So how’s it going? Well, the number of people crossing has fallen by 36% against the previous year, from 45,774 to 29,437, largely because of an agreement struck in December 2022 to fast-track the return of asylum seekers from Albania. But the Border Force officials’ union expects them to rise again in 2024.

“Despite Cleverly’s protestations to the contrary, the lousy weather has played a significant role in the reduction in crossings,” says Diane Taylor, who covers asylum issues for the Guardian. “On Tuesday NGOs working in the migrant camps in northern France reported them to be full of people waiting to cross the Channel.”

Fundamentally, Diane says, “the ‘stop The boats’ gimmick won’t work because government is targeting a symptom rather than tackling the cause of the problem. Safe and legal routes agreed internationally, not just by UK, will go a long way to stopping the boats – you never see Ukrainians in small boats.” But there is no sign of the government heading in that direction, even as its Rwanda removals policy continues to founder.

Verdict: Some progress, but failing overall