Final preparations are under way at Cape Canaveral in Florida for a milestone mission to put a US lander on the moon, an achievement not seen in more than 50 years since the end of the Apollo project.

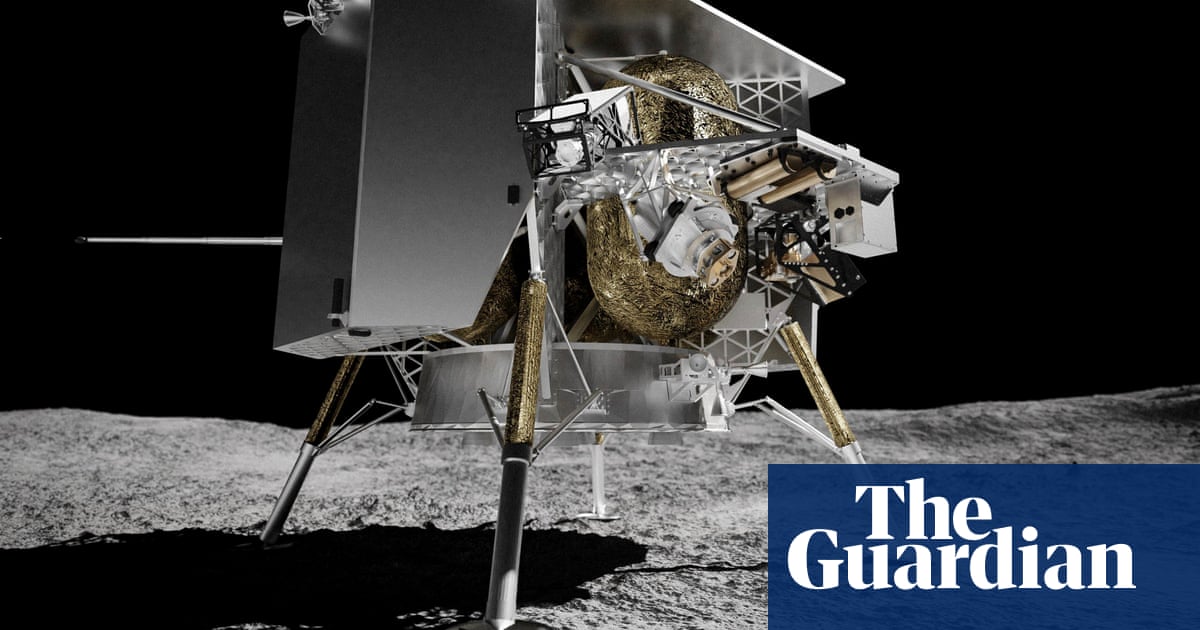

Last-minute glitches aside, Peregrine mission one, named after the fastest animal on Earth, will roar into the sky at 7.18am UK time Monday. After looping around the planet, it will head to the moon and slip into lunar orbit before an attempted landing soon after local sunrise on 23 February.

Even in the white-knuckle world of space exploration, the mission is considered risky. While Nasa has instruments aboard the robotic lander, this is a commercial operation. No private company has ever achieved a soft landing on the moon or any other celestial body.

“There’s a lot riding here,” said John Thornton, the chief executive of Astrobotic, the Pittsburgh firm leading the mission. “It’s a mix of emotions. There’s thrill and excitement, but I’m also a bit terrified because there’s a lot on the line.”

Adding to the nerves is the fact that the Vulcan rocket Peregrine sits on has never flown before, though its manufacturer, United Launch Alliance, has had a 100% mission success rate with its predecessor rockets.

Peregrine is the first mission to fly under Nasa’s commercial lunar payload services (CLPS) initiative, a new scheme in which the space agency pays private companies to deliver scientific equipment to the moon. Peregrine carries five Nasa payloads and 15 others. One, a shoebox-sized rover from Carnegie Mellon University, is set to become the first US robot to take a spin on the moon.

“This whole task is not easy,” said Chris Culbert, the CLPS programme manager at Nasa’s Johnson Space Center. “Landing on the moon is extremely difficult. We recognise that success cannot be assured.”

Not all the payloads are scientific: along for the ride is a copy of Wikipedia, a physical coin loaded with one bitcoin and DHL “moonboxes” carrying mementos ranging from novels and photographs to a small lump of Mount Everest. Also onboard, courtesy of the space memorial firms Elysium Space and Celestis, are cremated human remains and DNA, some of which belong to Gene Roddenberry, the creator of Star Trek.

The latter payloads have proved divisive. In a letter to Nasa, Buu Nygren, the president of the Navajo Nation, emphasised that the moon was sacred to many Indigenous cultures, and said depositing the material was “tantamount to desecration”. In response, Culbert stressed that Peregrine was a commercial mission and that Nasa was not in a position to tell Astrobotic what they could and could not fly.

Peregrine is bound for an ancient lava flow called Sinus Viscositatis, or the Bay of Stickiness, so named because the formations suggest the lava had an unusual consistency. If all goes well, Peregrine’s instruments will measure radiation levels, surface and subsurface water ice, the magnetic field, and the extremely tenuous layer of gas called the exosphere. The readings are expected to help minimise risks and harness the moon’s natural resources when humans return to its surface.

“It is high risk, for sure, but we knew that when we got into this game,” said Simeon Barber, a senior research fellow at the Open University and the lead UK co-investigator on the Peregrine ion-trap mass spectrometer, or PITMS instrument, a mini mass spectrometer that will sniff molecules as they bounce along the moon’s surface.

PITMS will analyse the composition of the lunar exosphere and monitor how it changes over the eight or so Earth days that the lander will operate. Researchers hope to see the effect of natural cycles, such as temperature swings from 100C to -100C, and the lander’s own activities. “We’ve asked the rover team to do a doughnut to kick up some gasses,” Barber said. “They said they’ll try.”

As a potential resource for future missions, water is a key molecule to find. PITMS may reveal how water molecules are released from the surface during daytime and trapped again at night, shedding light on the circulation of lunar water.

Peregrine is but the first in a wave of landers destined for the moon under the CLPS scheme. The next, built by the Houston-based Intuitive Machines, is due to launch in mid-February. It will take a more direct route to the moon and may even touch down before Peregrine.

While many scientists welcome the surge in commercial interest in the moon, some have called for agreements to protect sites of special interest, such as potential future bases for lunar telescopes or gravitational wave detectors. “People should think about this now,” said Prof Katherine Joy at the University of Manchester, a member of the Prospect science team, which will use a drilling and sampling instrument on a future CLPS mission to assess resources on the moon.

“We are a long way from space mining, but companies are taking those first steps to understand where would you go and what technology would you deploy. We need to think about the regulatory framework before things move too quickly.”