We watch old movies. We read old novels. So why shouldn’t we occasionally see old plays? That clearly is the belief of director Tricia Thorns and producer Graham Cowley whose Two’s Company has brought us, over the past 20 years, neglected work by Ernest Hemingway, James Saunders and NC Hunter among many others. This month they will be reviving, at London’s Arcola theatre, Don’t Destroy Me by Michael Hastings which created headlines when first seen in 1956 but which has since fallen into oblivion.

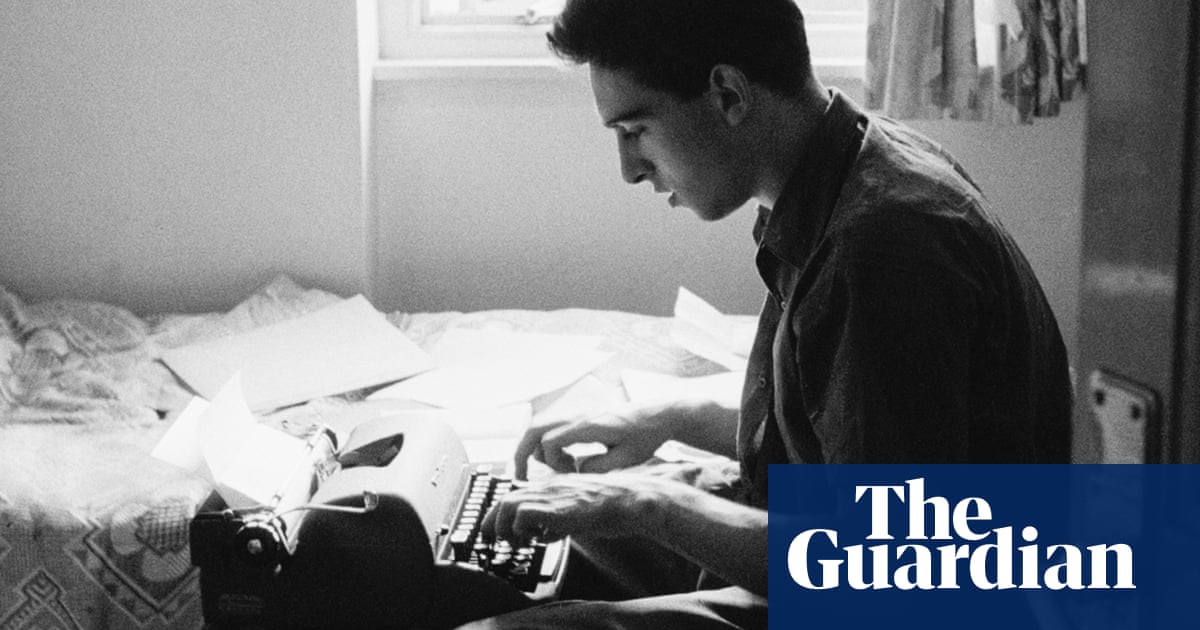

The main reason for the feeding frenzy in 1956 was that Hastings was only 18 and that his play opened a few months after Look Back in Anger had sparked the so-called Royal Court revolution. All the youth of England, if you believed the popular press, was on fire and Don’t Destroy Me was emphatically a young man’s play. It dealt with the travails of a Jewish teenager, Sammy, who after the death of his mother had been sent to live with an aunt in Croydon but who now found himself reunited with his drunken dad in a Brixton tenement. A lack of communication between the generations loomed large but the play’s energy sprang from its vivid portrait of a rackety community: best of all was a scene where a rabbi came to call, at Sammy’s behest, and was fed and fawned over before being finally expelled.

First staged at a fringe venue, the play was seen by George Devine who instantly commissioned Hastings to write a play for the Royal Court. The result was Yes, and After which was given a Sunday night showing in 1957 directed by John Dexter with a cast that included Heather Sears, Robert Stephens and Alan Bates: it would be good to see the Court resurrecting the idea of lavishly cast “productions without decor”. The play itself was a fascinating study of the trauma suffered by a policeman’s daughter allegedly raped by a now-vanished lodger. After that you might have expected Hastings to become a regular Royal Courtier but it was eight years before he wrote another play. In the interim he travelled extensively but, while writing novels and poetry, became the missing man of British theatre.

He did eventually return, writing factual dramas about Lee Harvey Oswald and Saint Just, a Wesker-style work-play, The Cutting of the Cloth, based on his time as a tailor’s apprentice, and exuberant works on racial themes including Gloo-Joo and Carnival War a Go Hot. He also wrote prolifically for television as well as biographies of Rupert Brooke and the explorer Sir Richard Burton. As Michael Coveney wrote in his 2011 obituary, Hastings was “unclassifiable” but two things strike me about him: he had the voracious enthusiasm of the autodidact and, in his work for the theatre, was always intrigued by loners, misfits and outsiders.

You see this in his most famous play, Tom and Viv, which caused ructions when first produced in 1984. There was much huffing and puffing at Hastings’ presumption in daring to write a play about the ill-fated marriage of TS Eliot and Vivienne Haigh-Wood. Whatever the truth of the accusation that Eliot connived at having his wife certified insane, the play left two deep impressions. One was that The Waste Land, far from being a work of studied impersonality, reflected the poet’s own inner turmoil and that there was much truth in the upper-class Viv’s remark to Tom that “I married you to escape my family: you married me, it seems, to embrace everything they stood for.”

But Hastings’ best play was The Emperor (1987) which he jointly directed and adapted with Jonathan Miller from a book by Ryszard Kapuscinski about the Ethiopian ruler Haile Selassie. This united Hastings’ preoccupation with Africa and his fascination with loneliness. On the one hand, the play offered a plausible portrait of the medievalism of Haile Selassie’s court but it also purveyed the eternal solitude of power with the sleepless emperor wondering how he could lead a revolution against his own authority. However hard it is to categorise him as a writer, the battles of Hastings were always internal and to do with our own contradictions.