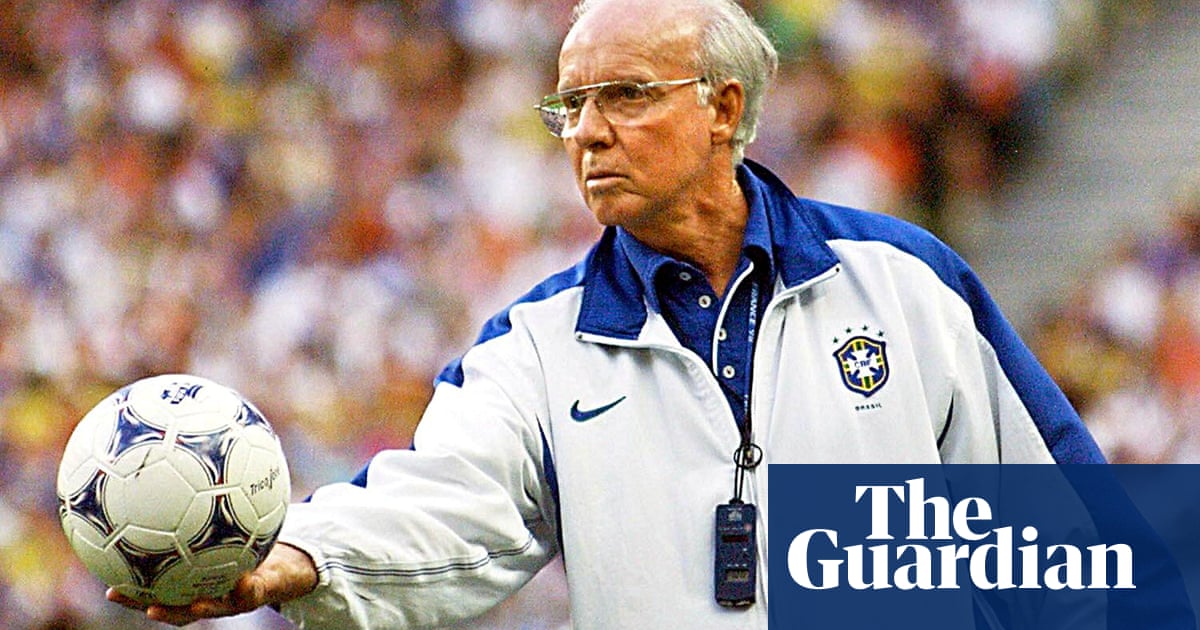

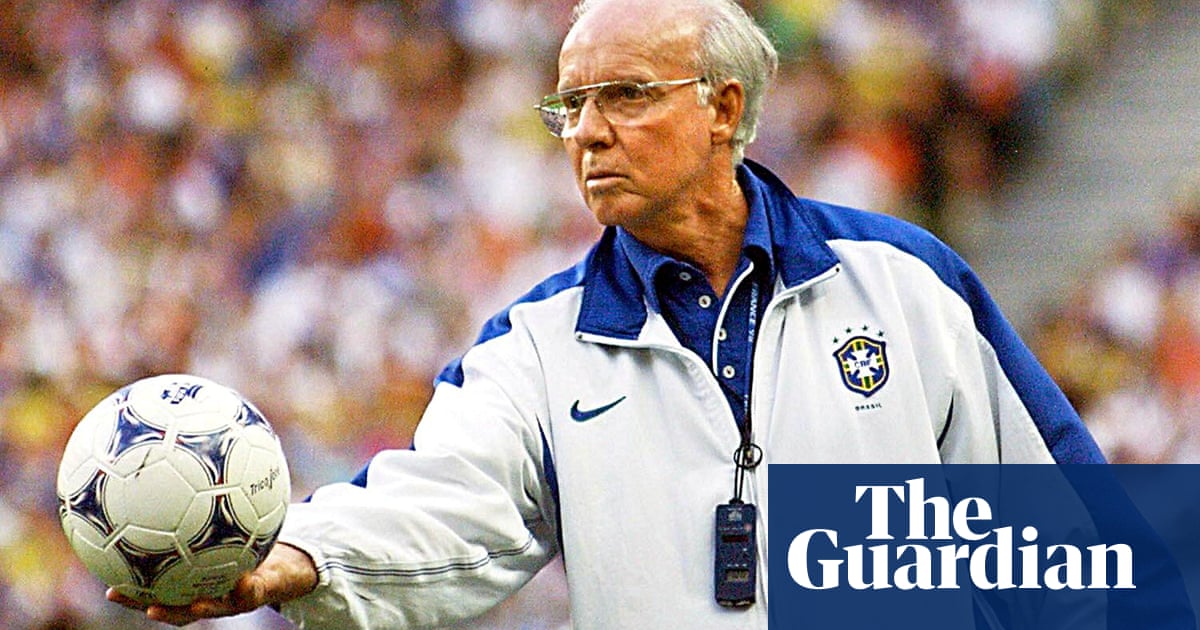

On a winter morning in 2013, I jumped out of a cab to meet my interviewee in a seaside condominium on the Avenida Lúcio Costa. In his 80s, Mário Jorge Lobo Zagallo, who was waiting in the lobby, remained football royalty. For decades, Zagallo and Brazilian football fed off each other in a wonderful, symbiotic relationship and achieved victory after victory.

Zagallo ignored my first question, but instead expanded on and dissected his achievements and conquests. He was full-on vain. Here was a man who had spent a lifetime cultivating his own place in history, a man who would tell you of his glories, and would never pass on a chance to be thanked for his own largesse. He reminded me of Dadá’s words: “Zagallo never tired of telling us: ‘Guys, I want to be part of history!’”

Perhaps he had every reason to be so self-indulgent. Much of his career was a victory parade but, above all, he was the pioneer and the architect of the Seleção’s golden epoch. As a player he provided balance, shuttling up and down on the left flank. In simple terms, Zagallo explained that the “No 10 was a symbol, it was a very difficult position to attain and so I switched to the No 11, where I created the modern left-winger. That was my thinking.” He accepted his limitations. It was Zagallo’s intelligent introspection that allowed him to reinvent himself and ultimately shape Brazil’s fortunes on the global stage.

Zagallo had all the characteristics of a great player − perfect mastery of the ball, excellent positioning, a good dribble and a fine pass. But he was intelligent and shrewd enough to understand early on that he was no match for Didi and other midfielders of great virtuosity. As Roberto Miranda put it: “He was a good player, but he didn’t enchant.”

To achieve his ultimate objective of playing for Brazil, he ditched the No 10 position and picked a role he’d master, reinvent and perfect on the left wing: the deep-lying winger (ponta recuado). It was an unheard-of adaptation of the winger position. Chico, Brazil’s left winger at the 1950 World Cup, and other contemporaries simply attacked and limited their endeavours to the opponents’ half, but Zagallo dropped back and helped out in midfield. In his interpretation, wingers had the obligation to defend. A noiseless and nerveless operator, he thrived and won the Carioca championship three times with Flamengo. He understood that Brazilian football was a place where heroes were born. At Botafogo, Zagallo became a part of the club’s first star-studded generation that included Manga, Nílton Santos, Didi, Garrincha and Amarildo.

For the national team’s left-wing slot, Zagallo overcame competition from Santos’s Pepe, with his cannonball, and São Paulo’s Canhoteiro. They were more gifted; Zagallo was more intelligent. Brazil had pioneered the back four to get extra defensive cover, but playing a system with wingers left the midfielders with acres of space to protect in a 4-2-4 formation. Zagallo’s ingenuity to drop back solved this problem. Manager Vicente Feola resisted the idea but Zagallo’s industry was instrumental to Brazil’s maiden World Cup victory, in 1958. Four years later, with Pelé injured and the left-back Nílton Santos ageing, his contribution was even more vital. Brazil won again and Zagallo’s name became a byword for success.

Zagallo loved victory parades and he was formidable at engineering them. On 18 March 1969, near Praia Vermelha, an intimate and secluded beach at the foot of Sugarloaf Mountain, the CBD’s Antonio de Passo secretly met with Zagallo. De Passo wasted little time: talks with Dino Sani had broken down; did Zagallo want to become the new head coach of Brazil? There and then, the Botafogo coach accepted.

This assignment was the ultimate step up in his short coaching career. Zagallo felt a deep connection with the Seleção. Success with the national team was essential to his self-image. He was the perfect fit for the CBD. A nationalist, Zagallo belonged to the establishment. In addition, he was calm and reserved; everything João Saldanha, the endless raconteur and hot-headed agitator, was not.

Tostão said: “He was always a very conservative person − in the sense of being closely linked to power, linked to the CBD, the yellow shirt, and Brazil. Extremely vain, but from the technical and tactical point of view he was focused.”

That evening, Zagallo met the players for the first time and did what he always does in an opening address − review his own career. Then he asked his audience “to defend and attack in unison”, a maxim cultivated by the 1954 World Cup-winning German coach, Sepp Herberger. Zagallo said: “That is modern football, with solidarity, football that is played around the world.”

The Seleção were in turmoil but Zagallo explained where he wanted to take them. He was going to bring deeper thinking to the team. His predecessor, Saldanha, took control, playing 4-2-4, and breezed through the qualifiers against generally weak opponents. The attractive style that pleased the players and restored confidence in the Seleção, however, did not impress Zagallo. It left the midfield too exposed.

“And with 4-2-4, we had never won anything,” remembered Zagallo. “We started to win in a 4-3-3 formation, in which I, Zagallo, was chosen to run back and forth. So, when Brazil was in possession, I was the attacking left-winger. When Brazil lost possession, I dropped back and became a midfielder.”

In Zagallo’s view, Brazil had been heading in the wrong direction. The team needed quick adjustments for a better balance. And thus Zagallo did what he had done at the 1958 World Cup in Sweden, at the 1962 World Cup in Chile and as a coach of Botafogo: he turned the team into a living iteration of himself. In midfield, Rivellino replaced the hapless Caju as the third man or false left-winger. The left-footed Rivellino then was playing the Zagallo role, the deep-lying winger fundamental in the coach’s 4-3-3.

Even out of possession, Rivellino and the team had a responsibility – to track back and close down the space, to cover and defend. It was a great feat of Zagallo to instil his team with such a sense of duty. After all, Brazil were fielding five players with a claim to the No 10 shirt: Pelé, Rivellino and Jairzinho, who wore the shirt number at their respective clubs Santos, Corinthians and Botafogo, and Gérson and Tostão. “At the World Cup, our Seleção must always have eight men behind the ball when the opponent is in possession,” said Zagallo. “And this is in a normal situation because when there’s a heavy onslaught I want nine or ten men or even the entire team to defend.”

Once Brazil shed the W-M system for the back four in the 1950s, Zagallo’s preference for compact football was almost a natural evolution. Increasingly, Brazil had men behind the line of the ball when out of possession. Tostão explained: “Zagallo had this idea of compact football. When we lost the ball, he wanted us to track back; when we had possession to advance as one. So, it was more or less the model of modern football, with less of today’s intensity. Tactically speaking, Brazil was also revolutionary. As a coach and strategist, Zagallo surprised me. The coach of Cruzeiro sat pitch-side during the training. He talked to journalists and we did what we wanted. Zagallo held a tactical training every day.”