What is the Peregrine lander and what was its purpose?

The Peregrine lunar lander is a robotic spacecraft designed by the US-based lunar logistics company, Astrobotic. Loaded on to a rocket, and blasted into space, it is designed to deliver payloads to the surface of the moon, or the moon’s orbit.

Its first mission, Peregrine Mission One, launched on Monday 8 January and was intended to deliver scientific equipment to the Gruithuisen Domes region of the moon. Some of these instruments are designed to take readings that could minimise risks and lay some of the groundwork for Nasa’s Artemis programme, which hopes to enable a sustained human presence on the moon.

Also on the lander are instruments and equipment from the Mexican and German space agencies, as well as universities, companies and individuals in the UK and elsewhere. These include a physical coin “loaded with one bitcoin” and a Japanese “lunar dream capsule” that contains 185,872 messages from children from around the world.

What went wrong?

Peregrine successfully lifted off on a Vulcan Centaur rocket – a new type of methane-fuelled rocket – from the Cape Canaveral space station in Florida at 2.18am ET (7.18am GMT) on Monday. Approximately 50 minutes after launch, and at an altitude of 500km (311 miles) above the Earth, the lander separated from the rocket and continued on its journey.

The first sign of trouble came about 7 hours after launch, when the spacecraft was unable to reorient its solar panels to point at the sun, so its batteries could charge. The ground-based engineering team eventually managed to turn them, only for further problems to develop.

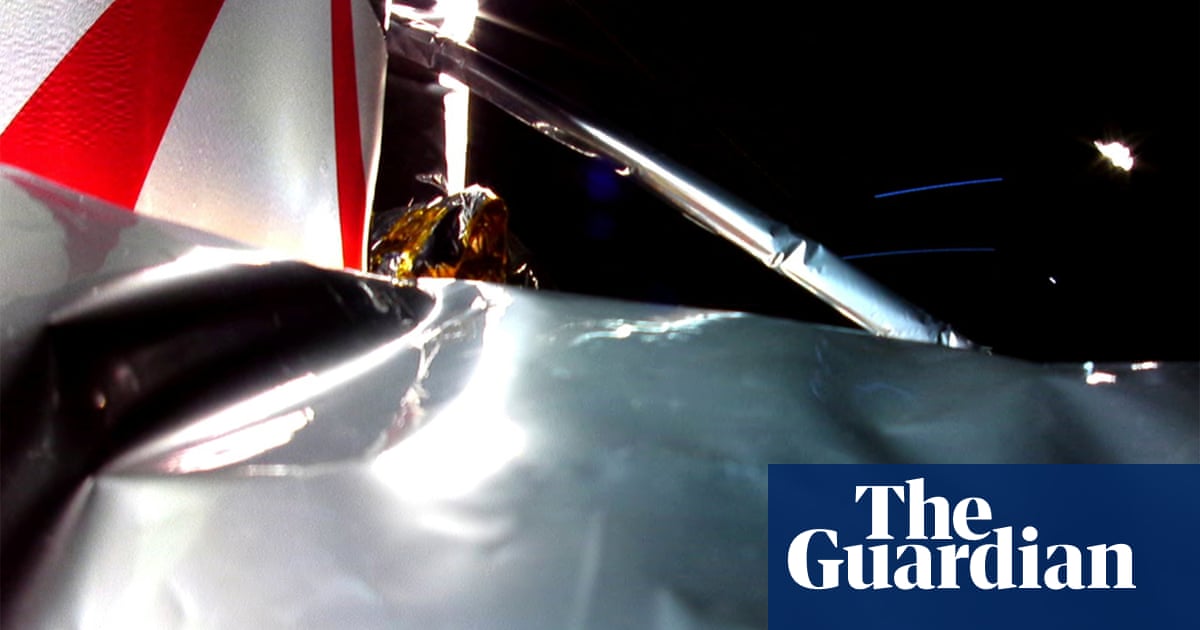

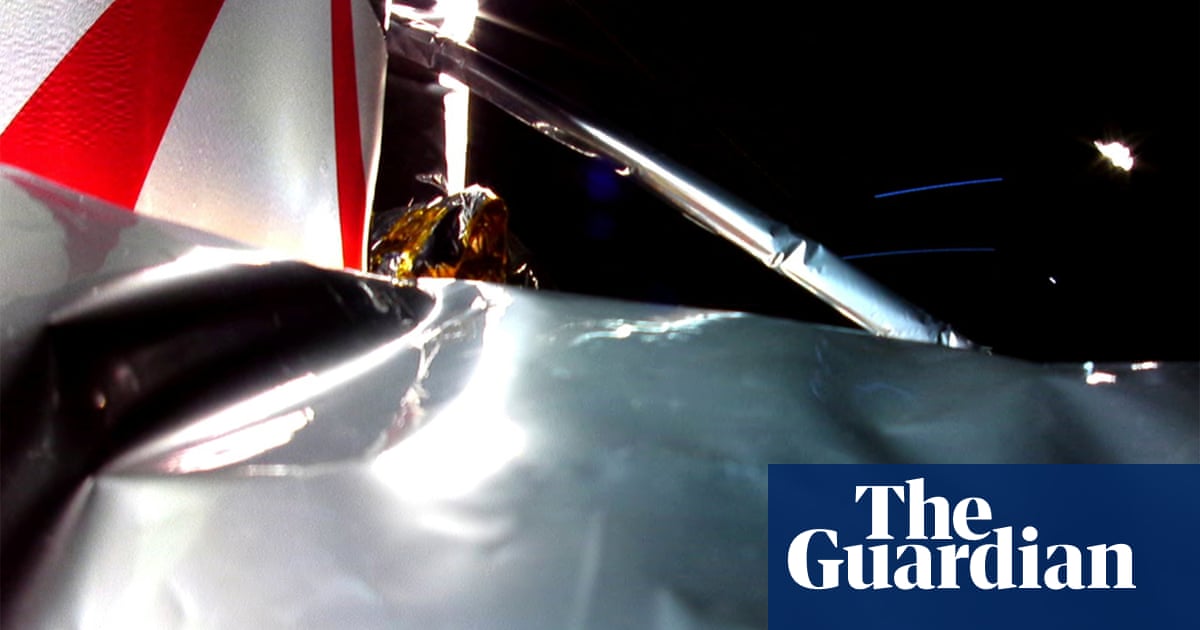

First, Astrobotic reported that it considered the root of the problem to be a failure within the vehicle’s propulsion system. Then it said this failure was causing a critical loss of propellant. “Given the situation, we have prioritised maximising the science and data we can capture,” the company said. Soon afterwards, Astrobotic shared the first image of the Peregrine lander in space, showing that its outer layers of insulation were crinkled.

On Monday evening, the company announced that the fuel leak was causing the thrusters of Peregrine’s attitude control system – designed to precisely align the lander – to “operate well beyond their expected service life cycles to keep the lander from an uncontrollable tumble”. Based on current fuel consumption, it said, the thrusters were only likely to continue operating for 40 more hours at most.

What will happen to the spacecraft now?

Peregrine was scheduled to land on the moon on 23 February, and even if it got there the 1.2-metric tonne spacecraft would need to reorient its engine to fire in controlled bursts during its descent.

Achieving this looks increasingly unlikely. In a statement posted on the social media platform X at 9.16pm ET on Monday, Astrobotic said: “At this time, the goal is to get Peregrine as close to lunar distance as we can before it loses the ability to maintain its sun-pointing position and subsequently loses power.”

Assuming the mission is abandoned, Peregrine will become another piece of debris, floating in space. It will also be a floating coffin, as among its contents are capsules containing DNA samples or portions of cremated remains from former US presidents, the science fiction writer Arthur C Clarke and others whose families have paid to land their remains on the moon.

Can anything be salvaged?

While propulsion and power system limitations may preclude a lunar landing, “the spacecraft’s robust scientific instruments and fully charged battery, combined with limited propulsion, open doors to valuable alternative goals”, said Dr Minkwan Kim at the University of Southampton. “With the exception of propulsion, all onboard systems can be rigorously tested against the harsh realities of space – extreme temperatures, intense radiation. This real environment test would provide crucial insights into system resilience and readiness for future lunar missions.”

What does this mean for future collaborative missions?

Peregrine Mission One may well become the third failed attempt by a private company to land on the moon, after the Beresheet lander and the Hakuto-R lander crashed into the lunar surface in 2019 and 2023, respectively. But many others are planned.

Nasa alone has multiple moon missions involving private spacecraft scheduled between now and 2026, and has emphasised that each mission is a high-risk, high-reward proposition. “Private-public collaborations unlock new avenues for innovation, often at a faster pace than traditional space agencies alone.

“While Peregrine’s lunar landing may not have come to pass, it’s crucial to avoid labelling it a complete failure,” said Kim. “Peregrine’s unique design and technology pushed the boundaries of what’s possible in lunar lander development, and the collaborations developed can be instrumental in driving down costs, paving the way for more frequent and sustainable lunar missions.

“Every challenge presents an opportunity to learn and refine our approach, making the next attempt even more likely to succeed.”