The 2024 US presidential election begins in earnest in Iowa on Monday, as Republicans in the midwestern state stage their caucuses, events through which their preferred nominee is selected. The process is hallowed but arcane. Here’s an attempt to explain.

What is a caucus?

Merriam-Webster, “America’s Most Trusted Dictionary”, defines a caucus thus: “A closed meeting of a group of persons belonging to the same political party or faction usually to select candidates or to decide on policy.”

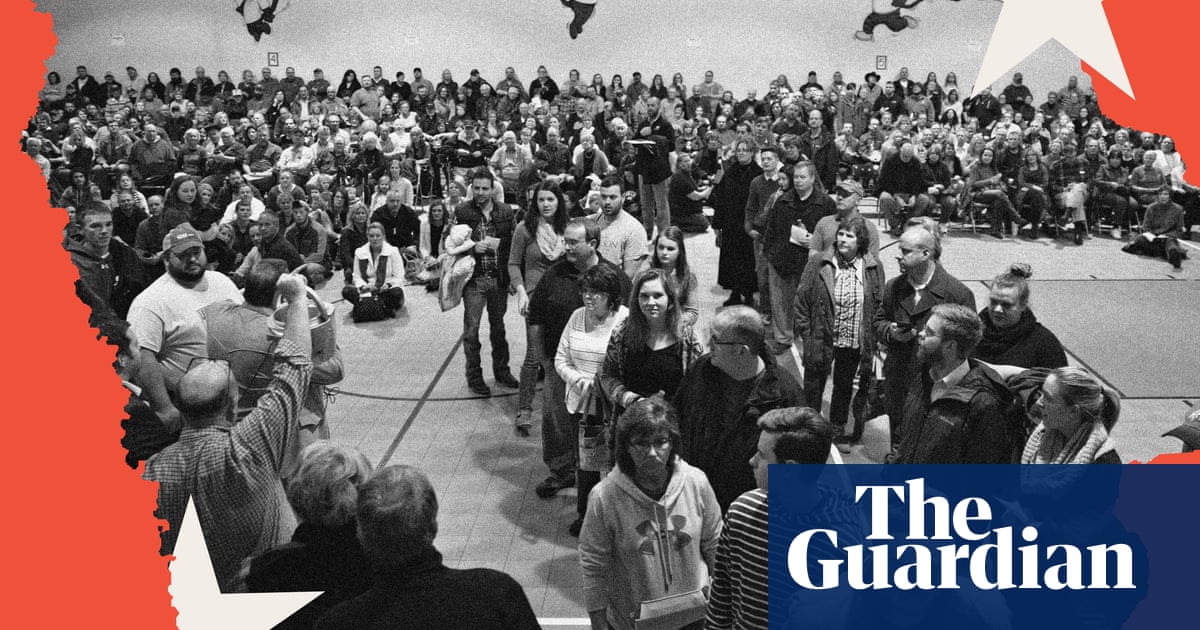

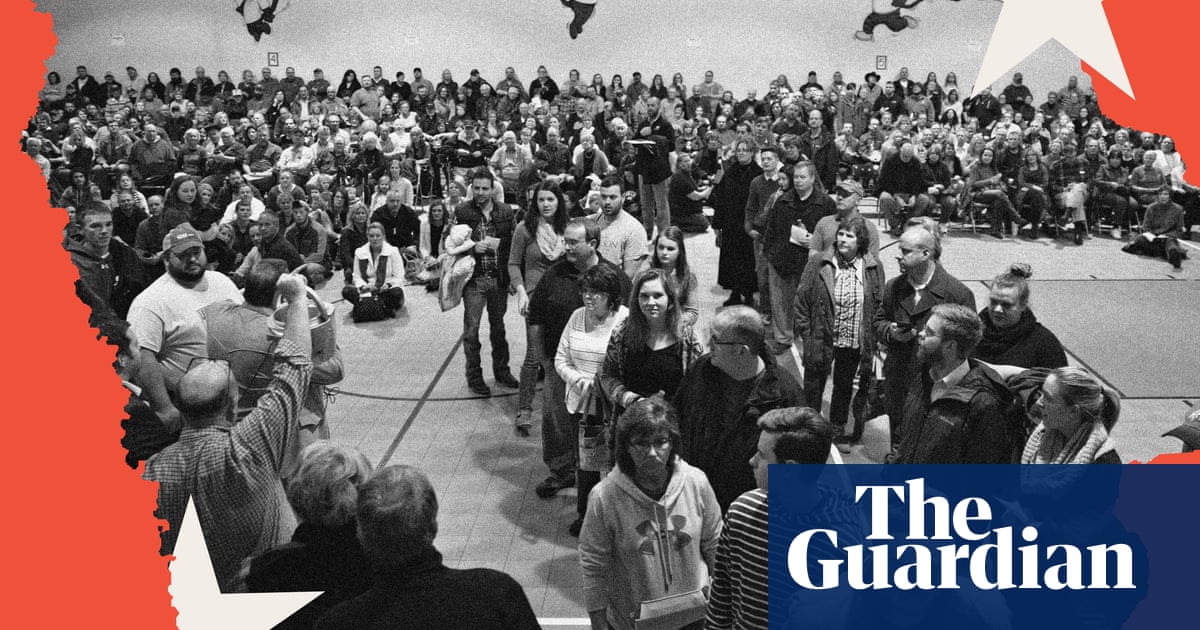

David Yepsen, a doyen of Iowa political journalism, boils it down: “A caucus – it’s a neighbourhood meeting.”

And as Tom Beaumont of the Associated Press explains, more than 1,600 such meetings will take place on Monday, “one for every precinct in the state”.

Either which way, it’s not a primary, the straight-vote contest held by most states, starting in New Hampshire next week.

How does a caucus work?

In Iowa, Republican and Democratic caucuses work differently. Now, after chaos and confusion in 2020, Democrats have made changes: they will meet on caucus day and conduct political business, but their choice for president will be made by mail and announced later.

Republicans are going ahead as usual. That means participants (registered Republicans only) will gather in each precinct at 7pm local time (8pm ET) on Monday evening, there to conduct party business, hear speakers and vote.

Here’s Beaumont again: “People sit together, some people stand up and speak on behalf of the candidates, and when that process is finished, people vote … on a secret ballot” – which is usually a simple blank slip of paper on which the voter writes the name of their chosen contender.

In terms of the presidential race, most votes “wins” Iowa. In practice, delegates to a state convention are awarded on a proportionate basis, so everyone “wins” – in a way.

Why does Iowa get to go first?

As the New York Times puts it: “Iowa got its spot by historical accident.”

Responding to a previous political fiasco, the protest-racked Chicago convention of 1968, Democrats wanted to give voters more of a say than party insiders in picking a nominee. In 1972, Iowa Democrats happened to schedule the first such contest. Four years later, Iowa Republicans did the same, while Jimmy Carter came from nowhere to win the Democratic caucus, the nomination and the keys to the White House.

“The power of going first thus clearly demonstrated,” the Times said, “the Iowa legislature passed a law requiring the state to continue scheduling its caucuses before any others.”

Is Iowa the right state to vote first?

Iowa’s first-in-the-nation status has long been questioned, given that it – like New Hampshire – is predominantly rural and white in a country trending ever more urban and demographically mixed.

On the flip side, Yepsen offers a historical nugget that points to a place in the tapestry of US life – “caucus is thought to be a Native American term, Algonquin for meeting of tribal leaders” – and even Iowa is changing: white children, for example, are now in a clear minority in Des Moines public schools.

If they were running a traditional caucus, the lack of diversity would be an issue for Democrats. But they aren’t, because of the fiasco last time and because of concerns about diversity. They now kick off with South Carolina, where Black voters saved Joe Biden in 2020.

For the Republicans, the question of whiteness is less of an (internal) problem. Heavily influenced by evangelical Christians, the GOP’s Iowa caucuses offer a reasonable indicator of the temperature inside the party. Eight years ago, the last time the GOP caucuses were competitive, Texas senator Ted Cruz courted evangelicals and won. This year, a key endorsement of Ron DeSantis notwithstanding, Donald Trump seems to have the evangelical vote sewn up.

Do Iowa winners go on to be nominees – or presidents?

Not always. Among the Democrats, the last winner of a competitive Iowa caucus was Pete Buttigieg, then the little-known mayor of South Bend, Indiana. He ended up endorsing Biden, his reward a cabinet post. Before that, in 2008, Barack Obama beat Hillary Clinton narrowly in Iowa and went on to the White House. In 2004, John Kerry beat John Edwards and won the nomination but lost the general election. In 2000, Al Gore won Iowa and the nomination but also lost to George W Bush.

Of late, fewer Republicans have won Iowa and the nomination. In 2016, Cruz lost the nomination to Trump. In 2012, Rick Santorum won Iowa but lost the nomination to Mitt Romney. In 2008, Mike Huckabee beat Romney but John McCain, fourth in Iowa, became the nominee. In 2000, Bush – a rare candidate with appeal both to evangelicals and moderates – was a clear winner on his way to the White House.

So losers in Iowa can win the race elsewhere?

Very much so. As Beaumont of the AP explains, for Iowa Republicans this year, “Donald Trump remains the dominant frontrunner [and] the race is essentially for second place. Nikki Haley is in the race for second place in Iowa. Should Haley beat Ron DeSantis, that would almost certainly signal the end of the DeSantis campaign and provide a lift to Haley, who is stronger than any other [non-Trump] candidate in New Hampshire.”