When he was a Ku Klux Klansman in South Carolina, Elwin Wilson helped carry out a vicious assault that left John Lewis with bruised ribs, cuts to his face and a deep gash on the back of his head. Half a century later, Wilson sought and received Lewis’s forgiveness. Then both men appeared on Oprah Winfrey’s TV show.

Wilson looked overwhelmed, panicked by the bright lights of the studio, where nearly 180 of Lewis’s fellow civil rights activists had gathered. But then Lewis smiled, leaned over, gently held Wilson’s hand and insisted: “He’s my brother.” There was not a dry eye in the house.

Raymond Arsenault, author of the first full-length biography of Lewis, the late congressman from Georgia, describes this act of compassion and reconciliation as a quintessential moment.

“For him, it was all about forgiveness,” Arsenault says. “That’s the central theme of his life. He believed that you couldn’t let your enemies pull you down into the ditch with them, that you had to love your enemies as much as you loved your friends and your loved ones.”

It was the secret weapon, the way to catch enemies off-guard. Bernard Lafayette, a Freedom Rider and close friend of Lewis, a key source for Arsenault, calls it moral jujitsu.

Arsenault adds: “They’re expecting you to react like a normal human being. When you don’t, when you don’t hate them, it opens up all kinds of possibilities. The case of Mr Wilson was classic. I’ve never seen anything like it in my lifetime, for sure.”

Arsenault, a history professor at the University of South Florida, St Petersburg, has written books about the Freedom Riders – civil rights activists who rode buses across the south in 1961 to challenge segregation in transportation – and two African American cultural giants: contralto Marian Anderson and tennis player Arthur Ashe.

He first met Lewis in 2000, in Lewis’s congressional office in Washington DC, a mini museum of books, photos and civil rights memorabilia.

“The first day I met him, I called him ‘Congressman Lewis’ and he said: ‘Get that out of here. I’m John. Everybody calls me John.’ It wasn’t an affectation. He meant it. He seemed to value human beings in such an equalitarian way.”

Lewis asked for Arsenault’s help tracking down Freedom Riders for a 40th anniversary reunion. It was the start of a friendship that would last until Lewis’s death, at 80 from pancreatic cancer, in 2020.

“From the very start I saw that he was an absolutely extraordinary human being,” Arsenault says. “I don’t think I’d ever met anyone quite like him – absolutely without ego, selfless. People have called him saintly and that’s probably fairly accurate.”

Arsenault was approached to write a biography by the historian David Blight, who with Henry Louis Gates Jr and Jacqueline Goldsby sits on the advisory board of the Yale University Press Black Lives series. The resulting book, John Lewis: In Search of the Beloved Community, examines a rare journey from protest leader to career politician, buffeted by the winds of Black nationalism, debates over the acceptability of violence and perennial tensions between purity and pragmatism.

Arsenault says Lewis “was certainly more complicated than I thought he would be when I started. He tried to keep his balance, but it was not easy because a lot of people wanted him to be what is sometimes called in the movement a ‘race man’ and he wasn’t a race man, even though he was proud of being African American and very connected to where he came from. He was always more of a human rights person than a civil rights person.

“If he had to choose between racial loyalty or solidarity and his deeper values about the Beloved Community [Martin Luther King Jr’s vision of a just and compassionate society], he always chose the Beloved Community and it got him in hot water. He, for example, was criticised for attacking Clarence Thomas during the [1991 supreme court nomination] hearings and of course he proved to be absolutely right on that one.

“There were other cases where if there was a good white candidate running and a Black man who wasn’t so good, he’d choose the white candidate and he didn’t apologise for it. He took a lot of heat for that. Now he’s such a beloved figure sometimes people forget that he marched to his own drummer.”

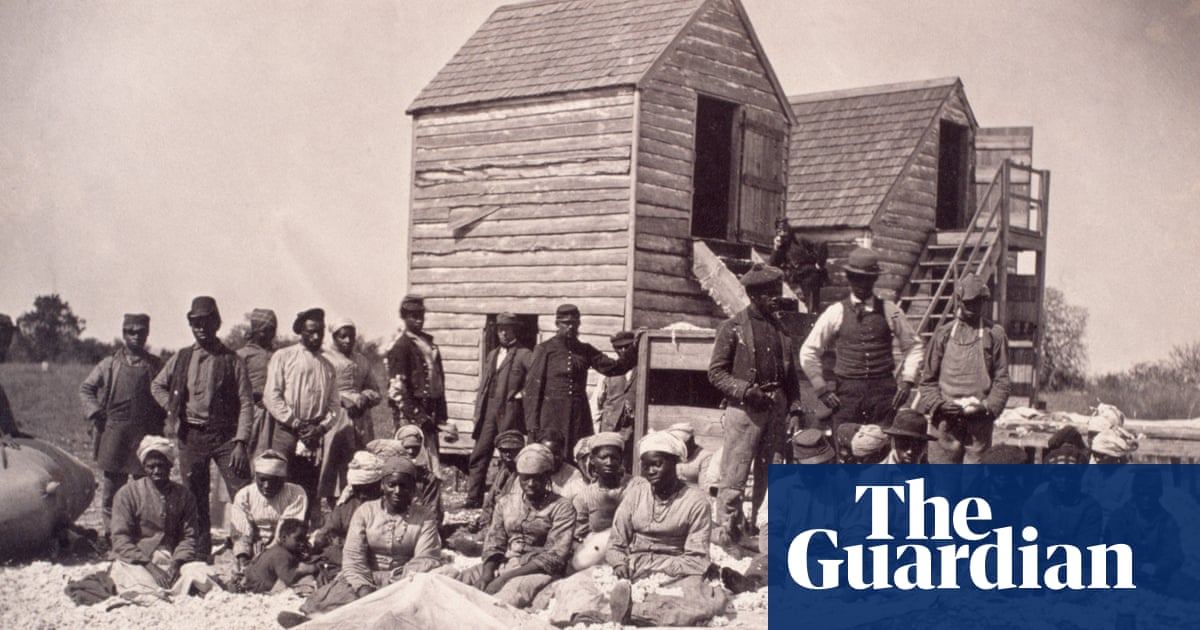

Lewis’s philosophy represented a confluence of Black Christianity and the teachings of Mahatma Gandhi, Arsenault says. “He had this broader vision. There’s not a progressive cause that you can mention that he wasn’t involved with in some way or another.

“He was a major environmentalist. There was a lot of homophobia in the Black community in those years but not even a hint [in Lewis]. He was also a philosemite: he associated Jews as being people of the Old Testament and he was so attracted to them as natural allies. Never even a moment of antisemitism or anything like that. He was totally ahead of his time in so many ways.”

‘A man of action’

Lewis was born in 1940, outside Troy in Pike county, Alabama, one of 10 children. He grew up on his family’s farm, without electricity or indoor plumbing, and attended segregated public schools in the era of Jim Crow. As a boy, he wanted to be a minister.

Arsenault says: “I have a picture of him in the book when he was 11; they actually ran something in the newspaper about this boy preacher. He had something of a speech impediment but preached to the chickens on the farm. They were like his children or his congregation, his flock, and he loved to tell those stories.

“But he was always bookish, different from his big brothers and sisters. He loved school. He loved to read. In fact his first protesting was to try to get a library card at the all-white library.”

Denied a library card, Lewis became an avid reader anyway. He was a teenager when he first heard King preach, on the radio. They met when Lewis was seeking support to become the first Black student at the segregated Troy State University.

“He was a good student and a conscientious student but he realised that he was a man of action, as he liked to say. He loved words but was always putting his body on the line. It’s a miracle he survived, frankly, more than 40 beatings, more than 40 arrests and jailings, far more than any other major figure. You could add all the others up and they wouldn’t equal the times that John was behind bars.”

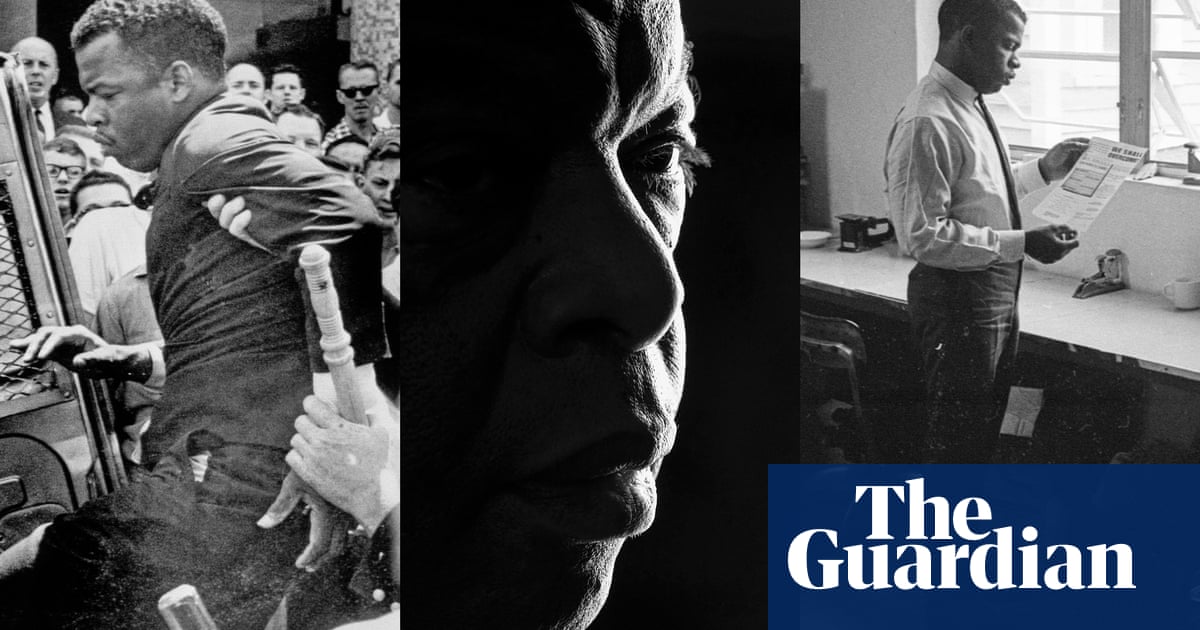

Lewis began organising sit-in demonstrations at whites-only lunch counters and volunteering as a Freedom Rider, enduring beatings and arrests. He helped found the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), becoming its chair in 1963. That year, he was among the “Big Six” organisers of the civil rights movement and the March on Washington, where at the last minute he agreed to tone down his speech. Still, Lewis made his point, with what Arsenault calls “far and away the most radical speech given that day”.

In 1965, after extensive training in non-violent protest, Lewis, still only 25, and the Rev Hosea Williams led hundreds of demonstrators on a march of more than 50 miles from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama’s capital. In Selma, police blocked their way off the Edmund Pettus Bridge. Troopers wielded truncheons, fired tear gas and charged on horseback. Walking with his hands tucked in the pockets of his tan overcoat, Lewis was knocked to the ground and beaten, suffering a fractured skull. Televised images of such state violence forced a reckoning with southern racial oppression.

Lewis returned to and crossed the bridge every year and never tired of talking about it, Arsenault says: “He wasn’t one to talk about himself so much, but he was a good storyteller and Bloody Sunday was a huge deal for him. He said later he thought he was going to die, that this was it.

“He passed through an incredible rite of passage as a non-violent activist and nothing could ever be as bad again. He’d been through the fire and so it made him tougher and more resilient. It’s origins of the legend. He was well considered as a Freedom Rider, certainly, and already had a reputation but that solidified it and extended it in a way that made him a folk hero within the movement.”

Lewis turned to politics. In 1981, he was elected to the Atlanta city council. Five years later he won a seat in Congress. He would serve 17 terms. After Democrats won the House in 2006, Lewis became senior deputy whip, widely revered as the “conscience of the Congress”. Once a young SNCC firebrand, sceptical of politics, he became a national institution and a party man – up to a point.

“That tension was always there,” Arsenault reflects. “He tried to be as practical and pragmatic as he needed to be but that wasn’t his bent.

“He was much more in it for the long haul in terms of an almost utopian attitude about the Beloved Community. He probably enjoyed it more when he was a protest leader, when he was kind of a rebel. Maybe it’s not right to say he didn’t feel comfortable in Washington, but his heart was back in Atlanta and in Pike county. As his chief of staff once said, wherever he went in the world, he took Pike county with him.”

The fire never dimmed. Even in his 70s, Lewis led a sit-in protest in the House chamber, demanding tougher gun controls. As a congressman, he was arrested five times.

“He was absolutely determined and, as he once said: ‘I’m not a showboat, I’m a tugboat.’ He loved that line. Nothing fancy. Just a person who did the hard work and was always willing to put his body on the line,” Arsenault says.

‘If he hated anyone, it was probably Trump’

Lewis endorsed Hillary Clinton in 2008 but switched to Barack Obama, who became the first Black president. Obama honoured Lewis with the presidential medal of freedom and in 2015, on the 50th anniversary of Bloody Sunday, they marched hand in hand in Selma. Lewis backed Clinton again in 2016 but was thwarted by Donald Trump.

Arsenault says: “He was thrilled by the idea of an Obama presidency and thought the world was heading in the right direction. He worked hard for Hillary in 2016 and thought for sure she was going to win, so it was just a devastating thing, as it was for a lot of us. He tried not to hate anyone and never would vocalise it but, if he hated anyone, it was probably Trump. He had contempt for him. He thought he was an awful man.

“That was something I had to deal with in writing the book, because you like to think it’s going to be an ascending arc of hopefulness and things are going to get better over time, but in John Lewis’s life, the last three years were probably the worst in many respects because he thought that American democracy itself was on the line.”

When Lewis died, Washington united in mourning – with a notable exception. Trump said: “He didn’t come to my inauguration. He didn’t come to my State of the Union speeches. And that’s OK. That’s his right. And, again, nobody has done more for Black Americans than I have.”

Arsenault says: “They were almost like antithetical figures. Lewis was the anti-Trump in every conceivable way, but when he died in July 2020 he probably thought Trump was going to win re-election. Within the limits of his physical strength, which wasn’t great at that point, he did what he could, but the pancreatic cancer was so devastating from December 2019 until he died.

“It was tough to deal with that part of the story but, in some ways, maybe it’s not all that surprising for someone whose whole life was beating the odds and going against the grain. He had suffered plenty of disappointments before that. It just made him more determined, tougher, and he was absolutely defiant of Trump.”

Lewis enjoyed positive relationships with Republicans. “He was such a saintly person that whenever there were votes about the most admired person in Congress, it was always John Lewis. Even Republicans who didn’t agree with his politics but realised he was something special as a human being, as a man.

“He had always been able to work across the aisle, probably better than most Democratic congressmen. He didn’t demonise the Republicans. It was Trumpism, this new form of politics, in some ways a throwback to the southern demagoguery of the early 20th century, this politics of persecution and thinly veiled racism. He passed without much sense that we were any closer to the Beloved Community.”

Lewis did live to see the flowering of the Black Lives Matter movement after the police murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis. He was inspired, a day before he went into hospital, to visit Black Lives Matter Plaza, near the White House.

“For him it was the most incredible outpouring of non-violent spirit in the streets that he’d ever seen, that anybody had ever seen,” Arsenault says. “That was enormously gratifying for him. He thought that in some sense his message had gotten through and people were acting on these ideals of Dr King and Gandhi.

“That was hugely important to him and to reinforcing his values and his beliefs and his hopes. I don’t think he was despondent at all because of that. If that had not happened, who knows? But he’d weathered the storms before and that’s what helped him to weather this storm, because it was it was so important to him.”

Lewis enjoyed fishing, African American quilts, sweet potato pie, listening to music and, as deathless videos testify, dancing with joy. Above all, Arsenault hopes readers of his book will be moved by Lewis’s fidelity to the promise of non-violence.

“When you think about what’s happening in Gaza and the Middle East and Ukraine right now, it’s horrible violence – and more than ever we need these lessons of the power of non-violence. [Lewis] was the epitome of it. You can’t help but come away with an admiration for what he was able to do in his lifetime, how far he travelled. He had no advantages in any way.

“The idea that he was able to have this life and career and the American people and the world would be exposed to a man like this – in some ways he is like Nelson Mandela. He didn’t spend nearly 30 years in prison, but I think of them as similar in many ways. I hope people will be inspired to think about making the kind of sacrifices that he made. He gave everybody the benefit of the doubt.”

John Lewis: In Search of the Beloved Community is published in the US by Yale University Press