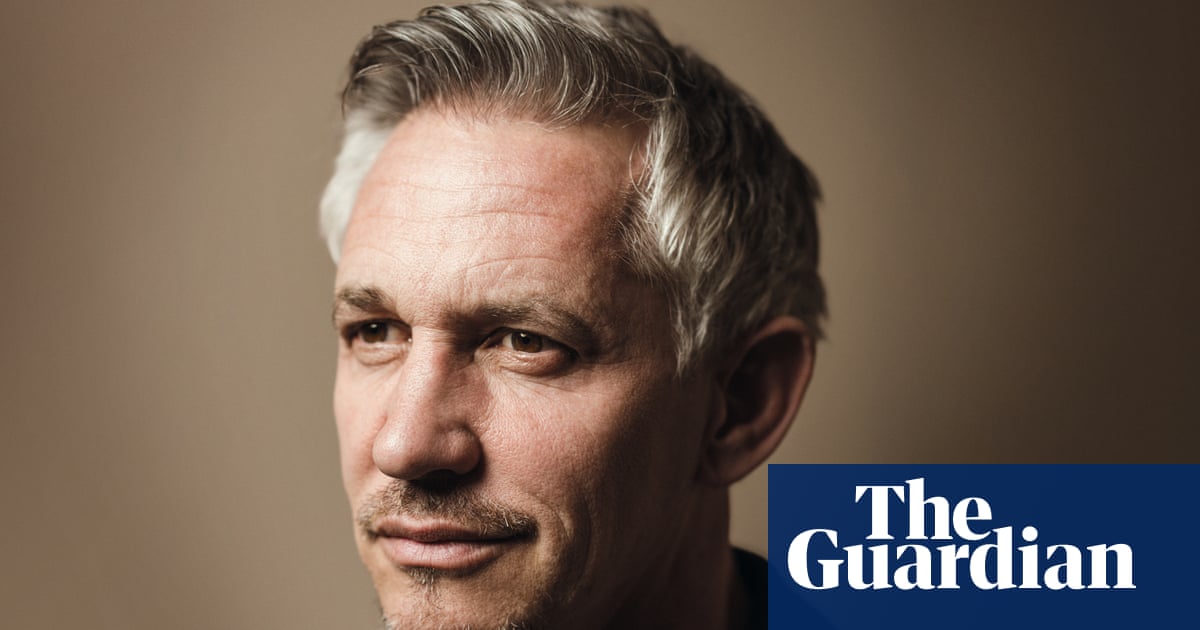

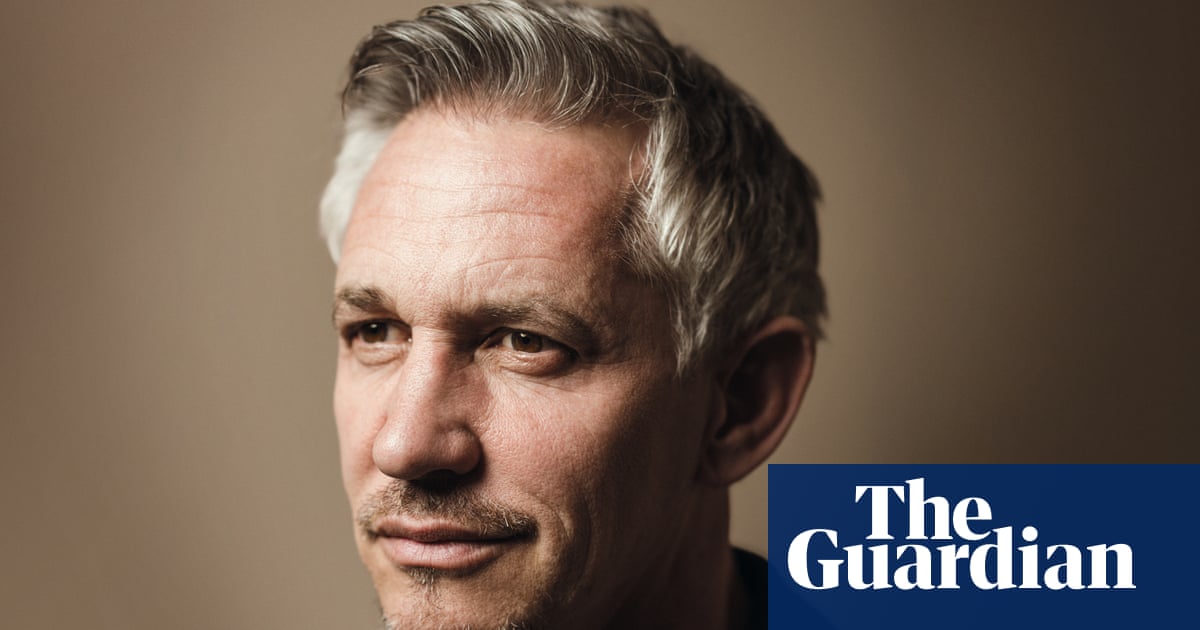

Gary Lineker has asked me to meet him at his house in Barnes at 2.30pm. It’s a miserable wet day in London, so I give myself time and arrive just before 2pm. As I turn into the narrow lane that loops round to his address, who should I see trying to squeeze past my car in a black Mini? His eyes slide towards me, then quickly back to the road. Gary Lineker! Where the hell are you going? I glance in my rear-view mirror to see his indicator blinking before he accelerates into a speedy getaway. I stop and check my phone. Sure enough, he’s crying off. “Could you do tomorrow?” he’s messaged. But I just saw you, I protest. Thirty seconds pass. He replies that he’s turning back. A couple minutes more and he’s home again, “So all good.” I pass the Mini again as I climb the porch steps and press the bell.

Lineker is in a black tracksuit and a little agitated. This is not the TV Lineker of Match of the Day, with his polish and cheeky grin. But then Lineker is entitled to have a scatty home version like the rest of us. He offers excuses – his plans changed; he got the wrong day; he was popping to the shops. He lives in a huge-roomed Edwardian house, once packed with four thudding sons, a second wife and stepdaughter, but empty now. Even the dog is out. But there’s a fire on in the kitchen and he makes tea. He’s not usually in the car, he says. There are only 280 miles on the clock and he’s had it a year. He walks – always walks – to the village. Takes the train or the tube in town. But it’s blowy out, and he had a huge pile of dry cleaning, still sitting on the back seat. As he places the mug beside me, I realise he’s embarrassed about the car. He’s an avowed environmentalist who retweets the Green MP Caroline Lucas and on at least one occasion defended Just Stop Oil. So Gary Lineker does not want to seem hypocritical?

Because, yes, there is also a “controversial” Lineker, who gets into scuffles online and whose pronouncements nearly cost him his BBC job. This Lineker is direct and risk-taking, and vocal pretty much since he logged on in 2012. He proclaimed on Brexit, (pro-remain), on Labour (anti-Corbyn) and has fought the Conservatives on every subject from sewage to asylum legislation. When you have a platform as big as his, he reasons – he has nearly 9 million followers – “You may as well use it to try to do good.” By good, he means worthwhile; earnest. In the course of the afternoon, he covers global politics, the state of the nation, activism. At one point he’ll say – so casually, at first I think he’s joking – that humans probably won’t exist in 50 years. “If we don’t blow ourselves up, we’ll burn ourselves up.” In Lineker’s worldview there are many ways in which we are hurtling towards disaster.

Mostly, though, he’s churned up about Gaza. He seems conflicted about whether to talk about the situation, but at the same time can’t stop himself. “Everybody I talk to, every single person I know, is going, ‘What? What is happening?’ But the minute you open your mouth – well, not my mouth, but the minute I tweet a little bit – it’s so toxic. If you lean to one side or the other, the levels of attack are extraordinary. How could it be controversial to want peace? I just don’t understand it. You don’t need to be Islamophobic to condemn Hamas, or antisemitic to condemn Israel. But at the moment it’s just awful. Awful.” When talking about the numbers of children killed, he says, “I feel sick.”

Some days after this interview, Lineker deleted a retweet of the Palestinian Campaign for the Academic and Cultural Boycott of Israel (PACBI), calling for Israel to be banned from international sports events, including football. A source said he misread the post as a statement the ban had happened. The tweet and its deletion caused an eruption of such ferocious anger – from all sides – that Lineker “has received threats. But it’s not about me. I am not the victim here,” he told me yesterday.

The more visible side of Lineker’s life was always his hugely successful career in international football. His accolades include 48 goals for England and the fact that in a 17-year career – playing for, among others, Leicester City, Barcelona and Tottenham Hotspur – he was never shown a red or yellow card. Football folded neatly into football punditry, most notably BBC’s Match of the Day, which he has anchored since 1999 on a published salary of £1.35m. Two years ago, he made a sideways move in co-founding Goalhanger, the now phenomenally successful podcast company that produces, among others, The Rest Is Politics with Alastair Campbell and Rory Stewart, and The Rest Is History. He hosts The Rest Is Football with Alan Shearer and Micah Richards, and the tone is blokey in a down-the-pub way.

Today he starts by saying that the podcast business has saved him from social media hell, being sucked into the ever-screamier vortex of culture war politics. He says he’s in a recovery of sorts from Twitter (now X) and has whittled his screen time right down (although a brief glance at his timeline might have you querying that). “Before,” he says, “if I was killing time like this morning, I’d just be trawling through social media, getting irritated and depressed by world news.” Those hours scrolling have been replaced by reading – “a lot” – and jamming in his earpods to listen to “pretty much” all of the 11 podcasts he produces, in addition to a couple of competitors he won’t name because – he grins broadly – “gosh, I don’t like giving plugs”.

In 2023, Goalhanger shows were downloaded an astonishing 236m times. One assumes that wasn’t all Lineker trying to stay off Twitter. He doesn’t listen to every episode ever – “That would take my whole life” – but “I listen when I’m walking to the shops, walking the dog, commuting, cooking.” He says he’s learned a lot from the drill-down long form of podcasting: “They can go into things in depth. Most of my Twitter posts now are trailing Match of the Day or my podcasts.”

Of course, there have been relapses. In one, with the prompt, “Worth 13 minutes of anyone’s time”, Lineker retweeted an interview with the Israeli academic Raz Segal in which he calls Israel’s action in Gaza “textbook genocide”. Uproar ensued on the grounds that the incursion did not meet the strict requirements for the legal concept of the word genocide. Lineker rolls his eyes. “But it wasn’t my opinion. It was [Raz Segal’s]. I thought it was well argued and worth listening to. It’s for others to decide what they think. For me, what’s going on is completely distressing. It’s another reason why I find it difficult to look at social media. Because I can’t bear looking at little children being killed constantly.”

What upset many in the Jewish community more than his empathy with the Palestinians was that before or since those tweets he’d said nothing about the Hamas atrocities on 7 October, the hundreds of hostages or the crimes of sexual violence. He says he hasn’t lost friends, “I’m not a falling out person”, but there are “associates” he’s chosen not to spend time with because “their views are so hardcore”. Most of his Jewish friends share his views: “But I don’t see it as a Jewish thing. I see it as the Israeli government. Obviously, they’re responding to 7 October, but crikey, one atrocity does not deserve 80 atrocities. Or more.” It’s true, he concedes, that he also has Jewish friends who disagree with him, including those who “have [privately] asked me to try to support Israel on Twitter, to back what they’re doing. I had to say, ‘What?! Look, absolutely no. And nor should you.’”

Perhaps it’s inevitable that with a platform his size, people will want him to take up their cause. In 2016, he was invited to dinner with Michael Gove, so that the Tory minister could sell him Brexit. “There was me and about 12 others, a couple of them with big platforms, that Gove was trying to get on board.” Lineker says he listened, thought “gobbledegook”, and asked Gove if this wasn’t actually a campaign for the leadership. “Categorically no,” Gove told him. “‘There is not any way possible that I would even consider that.’ Two weeks later he’s running to be the fucking prime minister.” There is a small irony in the fact that when Lineker tweeted in favour of remain, many of those politicians who wanted him to back Brexit howled that he was breaching BBC impartiality guidelines.

Similarly, all hell broke loose in March when he compared the then home secretary Suella Braverman’s rhetoric on immigration to 1930s Germany. He was suspended for a possible breach of those guidelines and hauled off air. Only briefly, because colleagues, including Ian Wright, Alan Shearer and Alex Scott, refused to perform their hosting duties in solidarity. Lineker was back in the chair the following week (“5-0,” the former BBC director general Greg Dyke quipped). He says he was deliberately precise with this tweet. “I worded it very carefully; I always do. Anything that is slightly borderline political, I put a lot of thought into.” He’d squared this with the BBC “in the early days” when he first got involved with supporting refugees. “I had an agreement that I could carry on with that and climate change because for me those are humanitarian issues and they’re going to get bigger.”

So there was no contravention as far as he was concerned when in November he criticised Braverman’s description of an Armstice Day demonstration against the bombing of Gaza as “a hate march”. “Marching and calling for a ceasefire and peace so that more innocent children don’t get killed is not really the definition of a hate march,” he wrote. Last month, after Lineker signed a letter protesting against the Rwanda policy, the defence secretary, Grant Shapps, told him that he knows “almost nothing” about politics and to “stick to football commentary and TV presenting”. The Daily Mail followed up with the front-page headline “Put a sock in it, Lineker”. Lineker gleefully retweeted it.

It is his strong view that footballers were political long before, say, Marcus Rashford baited Boris Johnson over free school meals. It’s just they didn’t have social media, he says. “Loads of footballers from my day are still political – Peter Reid, Neville Southall, to name two. But where could you have said anything before Twitter? No one’s going to ask you in a post-match interview, ‘So what do you think about what’s going on in Gaza?’”

Throughout our conversation he crosses and uncrosses his arms, his legs, touches his beard, thumbs his nostril, rubs his cheek. He doesn’t suffer from anxiety, he says, doesn’t get angry – “Not that red mist anger, but I get exasperated … and upset.” What upsets him? “Social media usually. Because it’s probably not brilliant for your mental health.” He adds quickly that he’s lucky with his mental health, but as he’s got older – he is 63 – he thinks “more deeply” about things.

It’s fair to say that Lineker was not the fully formed political activist he is today when he was, say, a striker for Barcelona in 1987. He grew up surrounded by politics and his father, Barry, a trader on a market stall in Leicester, was a solid Thatcherite. While he remembers being “absolutely enthralled by elections”, he was also driven as a footballer. “Focused. Cold, a little bit. I don’t think I’d have been as emotional or empathic as I am now.” What changed him? “Just living,” he says. “Educating myself. Having children. Feeling like one wants to fight someone’s corner when they’re in trouble.” He says any time he was supportive of refugees or asylum seekers on Twitter, there would be one recurring refrain: “You wouldn’t have them in your house, though, would you?” It gave him an idea. He signed up to the Refugees at Home charity and ticked “emergency foster service”. So far two young men have stayed, one from Turkey, one from Balochistan. Gokhan and Rasheed – around the same ages as Gary’s oldest and youngest sons.

“They are really lovely guys. Amazing stories. [Gokhan] is literally a rocket scientist – he’s on a full scholarship at Bristol University. I’m not allowed to say his story, but it’s fucking mad. [Rasheed] is from Balochistan. Everyone is going missing and being killed. He came here to study law so that he could try to go back and change things. Which is a long shot.”

Next time someone had that pop – Wouldn’t have them in your house, would you? – he replied, “Well, actually … ”

Lineker was born in 1960, the elder of two boys by Barry and his wife Margaret. He describes his father as “of his generation” when it came to expressing emotion. Barry worked long hours, six days a week, and lived life, as Lineker puts it. “He was a drinker and card player, a fisherman and smoker, but he was great. My mum was more like me, probably. She was chilled. Stable, loving. I never saw her lose her temper.” When he was in his twenties, his world was ruptured by his parents’ divorce. “It wasn’t great,” he says quickly, “because it made my dad very sad. I could hear him crying himself to sleep. She left him for another man, but we don’t talk about that.”

Lineker was a bright kid, lightning flash quick in that he ran 100m in 10.56 seconds. He told Sue Lawley on Desert Island Discs in 1990 how he and his brother Wayne were so sports-mad that when they played football in the garden on winter nights, they gathered lamps from around the house and set them in the back window as makeshift floodlights. If he hadn’t been a footballer, he says, he would have been a cricketer. Does he wish he’d studied politics or history at university? “I’m interested in them now, but I wouldn’t have been at 18. I went to Oxford, though.” He pauses, then smiles: “We lost 1-0.”

Football was always good to him. He recalls the joy of Barcelona from 1986-89: two hours training in the morning, then off to the beach for a late lunch. Home by five; siesta; dinner at 10pm; out late. “What a life! You had beaches and mountains. Good food. Great climate. I remember one Christmas Day sunbathing in the garden.” I ask about the high of goal-scoring and he says, “It’s hard to describe. It’s like watching your team score a goal, but times 50 – a one-hit multisecond explosion of emotion: relief mixed with overwhelming joy.” He’s discussed this with Alan Shearer and Michael Owen. They concluded, sadly, that nothing in life compares. “I mean, there are different pleasures in life – the birth of your child, the kids doing well, success at work. But that adrenaline, that explosion of joy, it’s irreplaceable.” Owen has racehorses, he adds. He’s a successful trainer. “But even a big horse race win doesn’t come close. Nothing, nothing can replace it. You have to accept that and deal with that.”

He frowns. Seems lost in thought, and I wonder if he’s recapturing that glorious moment. It turns out he’s thinking about something else entirely. “Don’t you think it’s bizarre, sitting on a horse? Do you think in the future we’ll say, ‘We used to sit on horses, how bizarre?’ because nowadays you see people riding elephants and everyone goes, ‘What the fuck are they doing?’ So even though I don’t have a huge problem with it, I do wonder. You wouldn’t sit on a dog, would you? I know they’re smaller, but I wonder what the horse thinks. ‘Oh fuck, he’s on my back again’? People say, ‘Oh they love it. They carry on when people are not on them.’ And I think, ‘They like running around!’ I like running around. But I don’t want to piggyback Gazza all over the pitch.”

Throughout the 90s and 00s, while Lineker was goal-scoring or raising his sons, or beginning his ascent up the broadcast ladder, he was put under illegal surveillance by certain tabloids. Shadowy figures were hired to tail him, photograph his every move; reporters were rummaging through his voicemails. Did he know? “No. Although, before it became public, my agent said, ‘Don’t leave any voicemails. I’ve got wind that the press is getting into phones.’ I never left voicemails. But you could tell that some stories had been written off the back of detail left in messages for me.” He can’t say more on specifics, having long settled his claim.

What he can say is that one evening, years later, he was watching Newsnight when the presenter turned to an item on phone hacking and criminal activity by UK newspapers. Up came photographs of Prince Harry, David Beckham, and then – he sat bolt upright – one of himself. A whistleblowing private investigator, formerly hired by tabloids, related how he’d followed him for two years. Lineker was shouting at his screen, “What?!” “But he was one of the clever ones,” the investigator said, “because he knew we were on to him.” “I was going, ‘Was I fuck?’ I never had a clue. They showed video footage of me on the golf course taken through a hedge. I swear I never knew. The investigator thought I was clever because I never led them anywhere. But I wasn’t messing about. All I did was play golf and go home.”

He was married to Michelle Cockayne, the mother of his four children, George, Harry, Tobias and Angus, between 1986 and 2006. In 2009 he married Welsh actor Danielle Bux, but they separated in 2016 because she wanted more kids and he didn’t. Bux is now married to American lawyer Nate Greenwald, with whom she has a daughter, and lives in Los Angeles. She and Lineker remain “best friends”. They speak daily. Aside from Barcelona, LA is the city he most often visits. He gets on with both exes – but Bux is the one that excites the tabloids. He was papped with her in Ibiza last summer.

He sits back in his chair and reflects that in this country, “We’ve got a great press and an awful press.” He says he doesn’t know what led editors and reporters to “lose their way” like this, but he has a theory. “Trying to catch people, track people: they had that real need to destroy people’s lives. I’ve never quite understood it. Maybe it’s the same thing that happens with people with power in government: when they start out, they’re not a bad person. But they get corrupted.” The further they rise, the worse it becomes, he believes. “Look round the world – at Putin, or at what’s happening in Israel, the people at the very top. I think it may be the same in newspapers. Owners, editors, they have this power. Often it seems to turn them bad. Not all of them, obviously,” he adds, hastily. “That would be a massive generalisation. But it’s always baffled me. I’ve met a few editors over the years and they seem all right. But I don’t understand that thing about trying to catch people out.”

Elements of the press are weirdly obsessed with me. It’s like a game for them to try to destroy me

Lineker is now stridently single. He’s dated a bit, he told the Times, but is always upfront about not wanting a relationship. He loves being single, he says to me. You are master of your own time; can do whatever you want. This has included teaching himself to cook, making huge elaborate meals over lockdown, even when no one else was around to eat them (to fully experience Lineker the cooking influencer, let me direct you to his Instagram highlights).

He suspects that “elements” of the press are “weirdly, oddly obsessed with trying to do me”. Do what to you? “Trying to like, put me away. They take everything out of context. Deliberately. It’s almost like a game for them to try to destroy me in some way. It’s very odd.” I ask whether his growing podcast empire and the power that wields is in any way threatening to traditional Fleet Street? “They won’t like that,” he says.

Podcasts are changing the landscape somewhat, he adds. “The genre is still growing, but it’s a real alternative to radio because you can find specifically what you want– comedy, news, politics, history. Radio, it’s always a bit hit and miss. I’ve completely stopped listening to it.”

Goalhanger also make sporting TV documentaries, but they quickly worked out that compared with the faff of documentaries – which “might only make a tiny profit”– podcasts were quick and easy to execute. Plus they make money. (The Guardian reported that Campbell and Stewart each make more than £100,000 a month, which would suggest company revenues run into millions.) “You say, ‘What about doing a podcast with two politicians, one left of centre, one right of centre?’ ‘Let’s do it.’ ‘Who will we get?’ ‘Alastair!’ You can do it the next day; maybe a bit longer, to get the right people. We’ve learned what appeals [to listeners] is the chemistry between hosts. They feel they know and like them. Episodes with a guest never do as well.”

Two downstairs rooms are filled with podcast equipment: desks, mics, LED ring lights. He says there’s a man cave downstairs where he watches football. This never gets boring. “Genuinely, it has been the one ever-present in my life. Kids have been around for half of it, a couple of marriages and my parents both gone a few years ago. Football is the one thing that’s always there.”

He refuses to say how he’ll vote in the next election, only that he’s voted all ways in his life. He’d like whoever gets in to “restore dignity to the country” and reintroduce fundamentally British qualities, such as respectability, decency, kindness, generosity. He’d like to see the return of “hope”. But he fears the election will be fought on “clickbaity, nasty things”, like immigration. The whole thing – the awful press, the bad actors in government, divisive leaders abroad – is a reflection of culture wars everywhere, he says. Without prompting, he asks what is wrong with being woke. “I mean, what is woke? Having a conscience, having a heart, having empathy? How is that a bad thing?”

While I can see that he’s vehemently disliked by some politicians and corners of the rightwing press for being outspoken, I don’t fully get his relationship with the tabloids. I suspect he’s a pragmatist, that he has sacrificed the sort of rage felt by people like Prince Harry and Hugh Grant in the name of public relations. He is friends with Piers Morgan, editor of the Mirror during some of its grossest hacking abuses, and a regular at Morgan’s Christmas pub drinks. Lineker laughingly describes their spats on Twitter as contrived. “Battling [with] Piers Morgan: we’d be going at each other and texting at the same time saying, ‘Keep it going! This is fun!’ All these things were very tongue in cheek.”

On Match of the Day and The Rest is Football he is also “tongue in cheek”: the ribbing, the guffaws, the freshness with which he can still experience joy in the game. Somehow, he walks a tightrope between his life as a pragmatist and a controversialist. The serious side that has drive and moral certitude versus a hunger for the adrenaline explosion that comes with a goal.

It’s getting dark outside. I’m conscious his dry cleaning is still on the back seat of the Mini. He looks at his watch. “Shops are open, just. If I’m quick.” Best not to suggest the car.