If you were a young person living in London in the early 1970s and you were looking for a bargain, the word of Nicholas Saunders was something close to holy scripture. Whatever you sought, Saunders had the answer. If you wanted to start an anarchist squat or self-publish a Trotskyist pamphlet, you consulted Nicholas Saunders. If you wanted to know how much a gram of cocaine should cost, or where to get free legal advice if you were arrested, you consulted Nicholas Saunders. If you just wanted to find out how to unblock a drain without calling a plumber, which supermarkets were cheaper for which goods, or how to fly all the way to India on a ticket to Frankfurt, you consulted Nicholas Saunders.

A tall young man with a wild beard that gave him the look of a shaman, Saunders was obsessed with documenting how the new global counterculture was changing the ancient city around him. In 1970, at the age of 32, he self-published his findings in a slim but dense guidebook called Alternative London. The book was testament to Saunders’ belief that information should be made available to all, and that this information should be rigorously tested. For the section on abortions, Saunders had a friend phone up each provider in the city, in the process uncovering a London-wide scam of clinics that marketed themselves as “cheap” but in reality were charging over double the non-profit rate. By 1974, Alternative London and its subsequent revised editions had sold close to 200,000 copies and become an underground bible.

Like many people who grow up around wealth, Saunders was attuned to how money flowed, and he loved circumventing official systems in order to find bargains for himself. “He didn’t want to spend any more money than he had to,” Anja Saunders, his partner during his final years, told me. “He was always looking to make something efficient.” In 1974, using £7,000 he had inherited from his recently deceased great aunt, he bought a former banana warehouse overlooking a triangular shard of courtyard in Covent Garden, which was going cheap owing to the looming redevelopment of its wholesale fruit and vegetable market. Two years later, Saunders started selling dry foods from the warehouse, enabling the type of people who had read Alternative London to stock up on rice, nuts and muesli for their communes. It was a success, and with the profits, Saunders added a bakery, a mill and a coffee roastery, all of which shared the same courtyard.

By the autumn of 1977, the coffee house was thriving and Saunders needed new premises. Anita Le Roy, a customer at the warehouse, recalls Saunders coming to the furniture shop where she worked with a proposition: “Want to start a business?” At 28, she knew nothing about coffee sourcing and less about business, but she was exacting about taste. She agreed – on the condition that she choose the coffee. In 1978, Saunders found a property nearby that could fit a roaster in the basement. He and Le Roy filled out the interior with wooden cubicles that looked like confessional booths, in imitation of the old Jacobean London coffee houses. They named the business after the street it was on: Monmouth Coffee.

Saunders was always looking for the next thing, and if it didn’t already exist, he would make it himself. In the winter of 1978, back in London after a holiday in Greece, he found himself craving proper Greek yoghurt: dense and creamy with a lactic tang and golden skin. This was a time when supermarkets mainly sold yoghurts with added sugar and flavouring, while unadulterated yoghurt – a pallid, joyless thing – was sold in health shops run by puritanical hippies. In search of his perfect yoghurt, Saunders scoured libraries for recipes, consulted a man called “Nick the Greek” who supplied all of London’s Greek restaurants, forced friends to bring back souring yoghurt on the plane and even went to the island of Paros to grill farmers. Everyone told him the same thing: it’s not possible.

Most people would have given up, but Saunders was not most people. “Anyone can do it,” he was fond of saying to sceptics. “It’s really quite simple.” The next year, he decided to start a dairy. He enlisted the help of a friend at the bakery, who, in turn, recruited Randolph Hodgson, a young man with a cherubic face and mop of blond hair who had just completed a food science course. Saunders, who was suspicious of insider knowledge, bluntly told Hodgson his degree was useless. Still, Saunders saw in him a pleasing willingness to try new things and he tasked Hodgson with the yoghurt project.

When the dairy opened in July 1979, it did indeed sell its own yoghurt. Unfortunately, it tasted disgusting. It wasn’t until a few weeks later that staff realised the vile taste had been caused by the newly varnished incubation cupboards. After a few months, the dairy found its feet selling ice-cream and homemade soft cheeses. Eventually, even the yoghurt began to taste good. As with Monmouth Coffee, the new business was given a name with a nod to its location: Neal’s Yard Dairy.

Almost 50 years later, the dairy and coffee house Saunders helped conjure out of nothing have been almost inconceivably influential. There is strong evidence to suggest that the first commercially made flat white served in the UK was made with Monmouth beans, while if you walk into a cheese shop in the UK today, there’s a good chance the monger will proudly say they worked at “The Dairy”, without having to qualify which one. They are not only “the yardsticks by which other cheese shops and coffee emporiums are judged”, according to the writer Matthew Fort, but have also been responsible for the success of artisanal food producers across the country who have revived – in some cases, reinvented – British food traditions. While the 60s counterculture helped export British music, films and theatre to the world, today we also export our chefs, produce and restaurant culture. In 2021 alone, Neal’s Yard Dairy sold €1m of British cheese to France.

Yet Saunders himself remains relatively unknown. When he died in 1998, he received few obituaries, and since then his fame has receded further. Even now, it’s hard to pin down exactly who Saunders was, not least because he was so many things at once: a hippy, a capitalist, a pioneer, a property developer, a drugs advocate, a social inventor, a greengrocer, a visionary. Yet a consistent philosophy guided everything he did: he believed, above all, that information should be wrested from gatekeepers and made free for people to use. “He didn’t just make information available, but made you feel like anyone has the capacity to go and do it,” Hodgson recalls. “He lit a fire inside people.” With this philosophy, Saunders’ dairy and coffee house have not just been influential in their own field; together they have been the two transformational businesses in the modern British food culture.

From the vantage point of the 21st century, it’s difficult to fully comprehend how dire British cuisine once was. “We are notoriously the worst and most wasteful cooks in Europe,” a British food journal of 1870 begins. It would get much worse before it got any better. The twin ruptures of the Industrial Revolution and rationing during both world wars, which didn’t fully end until 1954, meant that knowledge of traditional food production ceased being handed down. At its low ebb, British cuisine was characterised by the hangovers of wartime austerity: sandwiches lubricated with mayonnaise made from water, flour and powdered egg; waterlogged cabbage; hotels serving French food that resembled la grande cuisine as much an episode of ’Allo ’Allo! does a Jean Renoir film. Even worse was the decline of British produce. Shops sold chalky, greying bread made with adulterated flour; tasteless, factory-produced cheese; and increasingly bland varieties of fruit and vegetables made homogenous for the supermarkets.

There are two well-worn narratives that explain how British food recovered. The first places the revolution in the 1950s with a small cadre of upper-middle class writers inspired by Europe and its peasant cooking, who asserted that good taste could be found in simple, unadorned cooking that relied on good ingredients. Postwar Britain under rationing was not an easy place to recreate this food. Garlic, so crucial to Elizabeth David’s 1950 debut Book of Mediterranean Food, was a rarity (the following year, it became the first luxury ever chosen on Desert Island Discs). David admitted that “the production of high quality foods in this country is so small … that only a negligible minority of people ever set eyes on [them].” The result was that peasant food became a desirable aesthetic for the upper-middle classes, difficult to maintain and available to just a few devotees.

The second narrative about the rebirth of British food converges on late-80s London, and the creation of the Modern British culinary movement in restaurants. In this version, a small cadre of upper-middle class chefs looked again towards France and the simplicity of Italian peasant cooking to transform British food. The techniques were European, but these chefs could call their new cuisine “Modern British” because the produce was British: sturdy Scottish and Cumbrian meat, native and regional cultivars of vegetables, farmhouse cheese made from cows fed on English pastures. (Today, when an ambitious restaurant opens in Britain, it will usually list the British food producers that supply it.)

These narratives are compelling, but they aren’t the whole story. Many other events occurred in Britain to improve its food: the arrival of immigrants from former colonies after the dissolution of empire; the stewardship of its institutions – caffs and fish and chip shops, particularly – by Europeans; the explosion in materials such as Formica that modernised cafes and espresso bars; the creation of the European Economic Community; the leaps in industrial techniques that improved its vernacular foods: biscuits, crisps, ice-creams.

But what the two dominant narratives miss most of all is what happened between the 1950s and the late 80s – namely the story of how British produce improved to reach the level those writers craved and those restaurants needed: how British farmhouse traditions were revived, how wholefoods and the organic movement shifted consumers’ diets and shopping habits, how the world-class produce being made by a tiny number of rural farmers found an audience in affluent city-dwellers. This revolution has many strands, but to explain it fully you have to look to another small cadre of upper-middle class members of the late-60s counterculture.

And at the centre of this scene was Nicholas Saunders.

Nicholas Carr-Saunders was born in 1938 into a wealthy family who lived at a 16th-century mansion, Water Eaton Manor, on the outskirts of Oxford. As a child, if Nicholas had a question that his father, Sir Alexander Carr-Saunders, the director of the London School of Economics, could not immediately answer, Alexander would retreat to his study. A few days later, he would present the young Nicholas with a thorough answer. The idea that the information you need could always be made available was a lesson that never left Saunders.

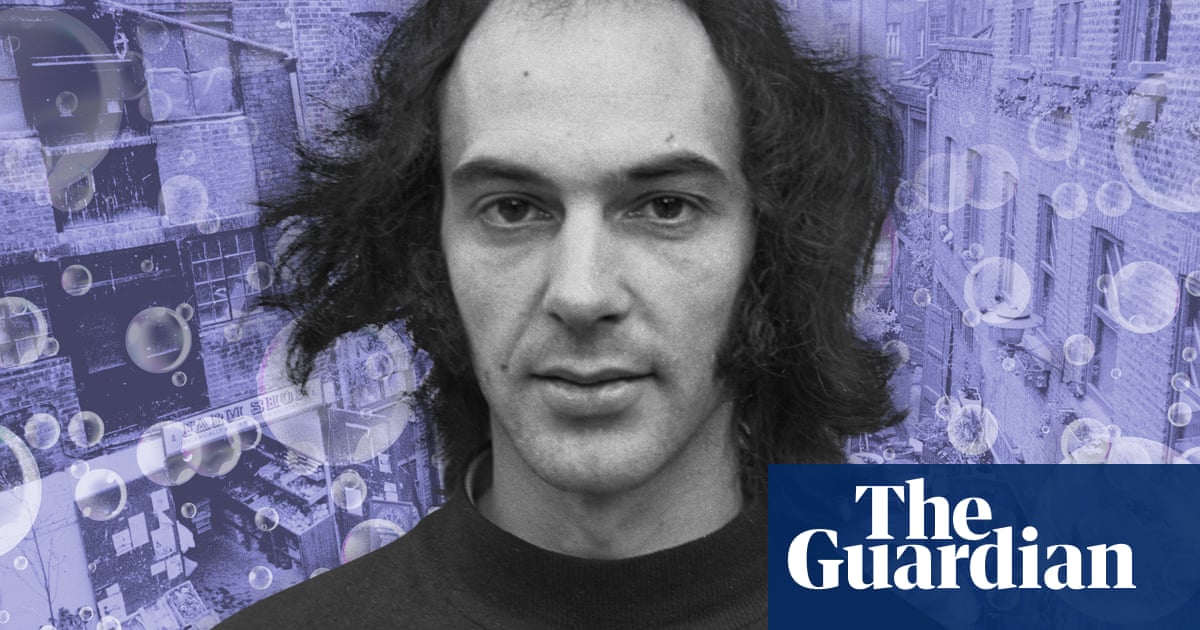

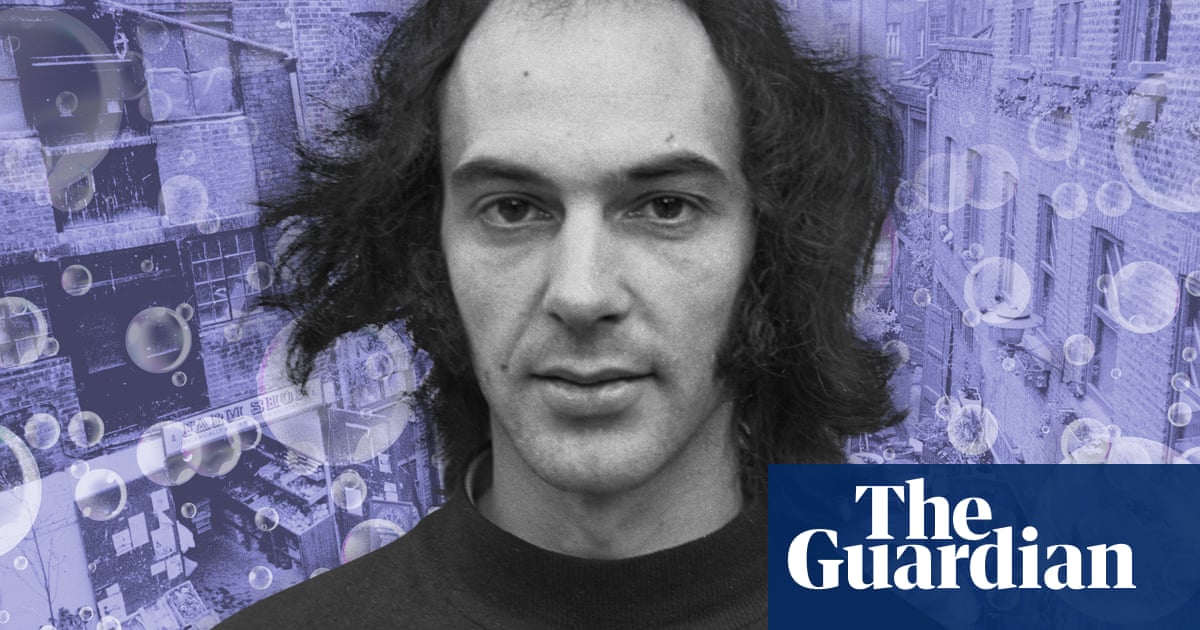

Nicholas moved to London in the early 1960s, just as the city was hoovering up a generation of hippies who had abandoned the pursuit of success and found inspiration in the mantra of the American author Timothy Leary: “Turn on, tune in and drop out.” It was a cultural shift that suited Saunders, who had dropped the “Carr” from his surname early – too posh, he decided – and whose relationship to authority was always antagonistic. (At Ampleforth, the Catholic public school he attended, he once stole ammunition and created a bomb, attempting and failing to blow up the chapel.) Saunders initially studied engineering, loving nothing more than to dismantle and reassemble things just to see how they worked, but he cut short his degree to live in the “alternative society” – a term he claimed to have coined – which was primarily made up of people like himself who could afford to drop out. In 1969, he took up residence at 65 Edith Grove – near Chelsea’s World’s End Estate, the centre of London’s counterculture – where he engineered an egg-shaped papier-mache cave at its centre. Passersby could always spot the house thanks to a contraption that blew bubbles out on to the street.

The Cave, as the flat became known, was not a hippy squat; Saunders owned the property and he didn’t let people forget it. But it soon attracted like-minded people interested in alternative ways of thinking. One of them was a puckish man called Nicholas Albery who worked for BIT, an underground information service that had been partly funded by a £1,000 donation from Paul McCartney. It was London’s answer to free information initiatives like Stewart Brand’s San Francisco-based Whole Earth Catalog – a publication Steve Jobs famously called “Google in paperback form” – that acted as the nerve centre of the alternative society.

Albery’s work inspired Saunders to write Alternative London, the aim of which was to arm countercultural individuals with the information that might allow them to thrive. Saunders and Albery styled themselves as “social inventors” and ran a competition called The Alternative Ideas Pool to encourage people to think up ways to improve the world. One contributor proposed breaking up the UK into 40 republics; another, not content with just one bad idea, suggested both a university built on a cruise ship and a “Love House” where people “could learn how to fuck”.

By the early 1970s, the utopian ideals of the 60s were being tested out in real world experiments. Saunders was fascinated by the back-to-earthers, who had retreated from cities to live a simpler, communal life. In 1973, he started research on a new book, Alternative England and Wales, which would take him around the country visiting communes. But visiting farm after farm left Saunders disillusioned: none of the people he met had found a way to live outside mainstream society in a sustainable way.

Meanwhile, the success of his books was so huge that what was meant to be a celebration of individuality was creating a new orthodoxy, with Saunders as its spokesperson. His friend Judith Morgan, who accompanied Saunders on his farm visits, recalls how impatient Saunders was to move on to the next thing, rather than repeat previous successes. “He would always look for how to exploit the system, or show the weaknesses in the system,” she says. But the more he did this, the more it catalysed a completely new obsession. What Saunders really dreamed of was creating the kind of communal village he could not locate for his book. When a Danish girlfriend meditating with a candle inadvertently burned down his highly flammable cave, Saunders was ecstatic. “I told her that the whole flat represented the life I wanted to leave behind,” Saunders later wrote. “It was the best thing she could have done for me.”

One day in 1976, Saunders was in a minivan laden with Brazil nuts when an idea came to him. He was making one of his regular trips to Freetown Christiania in Copenhagen, which had begun, five years earlier, as a squat in a derelict military barracks in Copenhagen and had grown into a large-scale experiment at building a society without centralised leadership, police or traditional family units. Christiania reminded Saunders of the energy of 60s London. It was, he felt, truly changing how people lived. There was a “real luxury of life there,” Saunders wrote in 1976. “Fresh wholemeal rolls with butter and strong freshly ground coffee for breakfast is normal. All the food is best quality – the organic vegetables straight from farming communes. I never saw anyone drink instant coffee.”

To pay for the cost of the trips, Saunders would load his minivan with Brazil nuts, which were expensive in Denmark owing to a luxury tax, and sell them to Christiania’s general store. On that day in 1976, in a minivan with his friend, the photographer Mark Edwards, Saunders realised that London’s health food shops were charging outrageous markups for foods bought from wholesalers he was already using, and that he could undercut them if he sold them in large amounts. Saunders thought of the now-empty warehouse in central London that he had bought two years earlier. By the time he passed Stratford, a plan had come together. “I mean,” Edwards recalls Saunders spluttering, “I could set it up in Neal’s Yard!”

At the time, the British counterculture was embracing wholefoods, which Saunders defined in Alternative London as food “farmed without the usual intensive techniques, free of additives and [with] the minimum of processing”. (In other words, organic-ish.) Wholefoods sold in bulk were favoured by people living in communes, who could stock up on essentials cheaply. But if you didn’t live in a commune, you could only buy wholefoods at expensive health food shops run by hippies who, in Saunders’ words, “would make customers feel bad because they could not recognise a mung bean”. Saunders hated these shops, which he saw as inefficient, expensive and exclusionary. If wholefoods were going to reach as many people as possible, he needed to offer something different.

Six months later, after his eureka moment on the way to Denmark, Saunders opened his wholefood warehouse in Neal’s Yard. It was decked out in the cheapest, utilitarian way possible, “Christiania style” as Saunders put it, using recycled materials from demolition sites. It sold staples in bulk: nuts, tahini, honey, oils, peanut butter and, most famously, muesli. A bakery and a flour mill, using a grinder imported from Christiania, soon followed.

Yet Neal’s Yard was less striking for what it sold than what it was: a secret village right in the middle of one of the world’s most mapped cities. Around this time, Le Roy, who worked around the corner, started to notice groups of “tattooed and beautiful people with feathers in their hair” emerging from what she had previously considered a dank, rat-infested courtyard. They were the wholefood warehouse workers, many of whom, Saunders later wrote in his autobiography, were secretly raiding the costume department of the nearby Royal Ballet Company, which they could access walking across the rooftops from Neal’s Yard.

Around Saunders, who now lived and worked in Neal’s Yard, a spirit of creative anarchism flourished. Workers moved sacks of produce from the ground floor to the packing floor by throwing themselves off the building on a rope to act as a counterweight. For a time, the yard was soundtracked by the squiggly hiss of film stock being rewound, as the Monty Python team, the only other people who had premises in Neal’s Yard, finished work on The Life of Brian.

Passersby assumed it was all a posh hippy commune, and in some sense they were correct. For all its democratic impulse, many workers in the warehouse either had the title “Honourable” before their names, had been to the same public school as Saunders, or were ex-Christianites. Some resented the increase in “straight” customers that the Yard’s success was attracting. In 1977, when a Daily Telegraph article flooded the Yard with people from the home counties desperate for bargain basement coffee, Saunders temporarily shut it down. He may have distrusted the “freaks”, but Saunders also realised that if too many “straights” came then the Yard’s alternative atmosphere could not be maintained. Days later, an irritated customer came by to harangue Saunders with his thoughts on the matter: “So you stopped selling coffee because you were too successful? How British. How disgustingly British.”

Unlike many in his scene, Saunders was not a leftist. He had no time for welfarism or state ownership, which he dismissed as inefficient, yet he also rejected rampant capitalism, which he saw as fundamentally unfair. He steered an alternative path, cultivating a community of businesses rather than the more radical Christiania-style community he had once envisioned. Saunders set out 12 principles for how the businesses in Neal’s Yard should operate:

1. All food must be prepared or at least packed on the premises.

2. The ingredients must be “wholefoods” ie pure, without any additives, such as flavouring, colouring or preservatives. Highly refined ingredients must be avoided.

3. Prices must be reasonable.

4. Descriptions (both verbal and written) must be straightforward, down to earth and objective. Persuasive, enticing or glamorising descriptions must not be used.

5. The size and style of notices must be simple – not attention-seeking, enticing, image-building or making any use of advertising or merchandising techniques.

6. “Point of sale aids” must not be used.

7. Information about recipes, ingredients, quality and suppliers must be freely available.

8. The neighbours must be given consideration and cooperation.

9. All staff must be free to see the accounts and attend meetings where they can freely express their views.

10. Jobs should be rotated as far as possible, and in particular no one should be left with the unpopular jobs.

11. Outside contractors should be avoided if the work can be done by the regular staff.

12. In the event of a business growing, it should not expand or set up branches, but instead assist and encourage some of its staff to split off and start another independent business.

If he had franchised the Neal’s Yard ethos, Saunders could have become another Richard Branson, a former hippy who had so carefully studied the vices of capitalism that he had learned how to become one of its most skilful exponents. What made him different was his habit of giving away his most successful businesses. “Nick would jump in at the deep end of things, try to figure everything out about them, take what he could and move on,” Edwards, the photographer, told me. Hodgson recalls Saunders, just three months after the Dairy started, marching him over to a bank on Pall Mall to sign over the entire business to him. It was only later, when Hodgson started doing business with other people, that he understood just how unusual this decision was.

Of all of the Neal’s Yard businesses, it was Hodgson’s and Le Roy’s – the Dairy and Monmouth – that cleaved closest to Saunders’s principles. To those who worked at either, it was less a job and more a lifestyle cult: employees sometimes switched from one company to the other, or attended shared tai chi lessons before work. In 1982, Le Roy and Hodgson married, serving coffee ice-cream at their wedding reception in the yard to edibly symbolise their union.

Saunders’s followers took inspiration from his 12 principles – but they quickly started to feel that the rules could be bent and sometimes broken. During the second year of the Dairy, Hodgson realised there was a limit on how much self-produced yoghurt he could sell. (It is Neal’s Yard lore that the Monty Python cheese sketch about a cheese shop that doesn’t sell cheese is based on John Cleese attempting and failing to order some cheese at the Dairy.) Hodgson decided to diverge from Saunders’ first rule and sell good quality hard cheese that wasn’t manufactured or prepared in the yard. This made no sense to Saunders, who was mainly interested in the effect that producing food could have on a person’s self-fulfilment rather than the actual quality. “I don’t think he was driven by how it’s going to make food taste better,” Hodgson says. “It was about how it grew the individual.”

Hodgson was driven by both possibilities, and set off round the country in a van, seeking out his own freaks: farmers who were committed to making their own cheeses with traditional methods that their grandparents might recognise. Like Saunders and his back-to-earthers before him, the search was demoralising. The number of farms that made cheese themselves had declined from more than 1,000 in 1939 to just 62 by 1974. But Hodgson found them, and created a new market by connecting these producers with consumers who had an appetite for weirdness. One former employee at the Dairy recalls Hodgson phoning up a farmer demanding that he raise his prices, a move that the bargain-hunting Saunders would never have been able to understand, but made the strange methods of the cheesemakers financially viable.

By the mid-90s, the influence of the Dairy had grown to the point that any cheese it sold was globally significant solely by virtue of being stocked there. Cheese shops in the US could show they were serious by buying cheddar from Neal’s Yard. The best British restaurants could prove they cared enough about native produce by removing the French cheese course that had traditionally punctuated meals and replacing it with cheeses from the Dairy. Trevor Gulliver, who opened the era-defining restaurant St John with Fergus Henderson in 1994, told me that “there was no one else”, when it came to deciding their cheese supplier, a relationship that has continued for 30 years.

During these years, what the dairy was doing for cheese, Monmouth was doing for coffee. James Hoffmann, one of the architects of Britain’s third-wave coffee movement, remembers coming to London in the early 2000s and being struck by how out of step Monmouth was with everything else going on. “At that time, coffee in England was a joke globally,” Hoffmann recalls. Monmouth was the only place in London doing good filter coffee, even if they didn’t advertise it. It was also transparent about where its coffee was from, a continuation of Saunders’ seventh rule. “They proved a model that people will pay more for better coffee that tastes of somewhere,” Hoffmann says, pointing to the coffee wholesalers and shops who built their businesses on the success of Monmouth.

Perhaps the most transformative legacy of the Neal’s Yard businesses is what they achieved when working together. One day in 1994, Hodgson was on his way to visit the Dairy’s new yoghurt production site in Kent when he noticed an unusual space under the railway tracks at London Bridge. The area was reminiscent of Neal’s Yard in 1976: derelict and located near a wholesale vegetable market in steep decline. Hodgson needed space. In the previous 10 years, the Dairy’s rent had shot up, and he saw that there was enough space under the tracks for both the Dairy and Monmouth, plus more left over. Like Saunders 30 years earlier, Hodgson realised the space’s potential. The Spanish food specialist Brindisa was also moving in, and Hodgson calculated that if more food businesses moved in alongside them, they could open up their warehouses at the weekends and sell to the public at wholesale prices. He told the food writer Henrietta Green, author of the Food Lover’s Guide to Britain, of his plans. When she asked Hodgson for the name of the place, he told her: “Borough.” (She answered: “Where?”)

The new incarnation of Borough Market opened in 1998. Though it was only the second regular farmers market in the UK – the first was in Bath – it was an immediate success, feeding a new culture that deemed it desirable, even fashionable, to eat well. The columns of Nigel Slater and the TV shows of Jamie Oliver broadcast to the world that the best produce in the UK, maybe even Europe, could be found at Borough. The market was telling the country a story about itself that it wanted to hear, of a Britain that was reviving its cultural history. Malcolm Veigas, an assistant director with Bolton Council, once gave an interview to the BBC’s Food Programme in which he cited Borough as the lightbulb moment for councils that wanted to harness the new interest in food to rejuvenate their areas. “Market professionals up and down the country, when they heard about what was going on in the Borough, realised that the future of retail markets in the UK was going to be predicated on food.”

By 2005, the reputation of British food had transformed so much that American food magazine Gourmet dedicated an entire issue to London, calling it “the world’s best place to eat”. In her introduction to the issue, editor Ruth Reichl named four places in the first paragraph: St John, Neal’s Yard Dairy, Monmouth Coffee and Borough Market.

During the years British food culture was being reshaped by his proteges, Nicholas Saunders had sunk into a deep depression. Although he had generously given away ownership of his businesses, the fact he continued to live in Neal’s Yard meant it was impossible for him to stop meddling. “For years I watched gloomily as my ideas were discarded and buildings were bought up by developers,” he later wrote, appalled at the encroachment of what he considered to be “straight” businesses.

Still, Saunders kept creating success for others. In 1981, distracted from the yard by the birth of his son, Kristoffer, he made plans to start an apothecary selling herbal remedies. He asked a friend, Romy Fraser, to run it. The business opened that same year as Neal’s Yard Remedies. With a turnover of £36m in 2022, it has become an international skincare empire and the most successful of all the Neal’s Yards businesses, instantly identifiable by its blue-tinted bottles (which Saunders, predictably, vehemently disliked for being flashy).

The 80s were a rough decade for Saunders, who was living alone and took little delight in the quality of produce his former businesses sold, preferring to eat Marks & Spencer’s ready meals. As ever, he continued to come up with new business ideas. In 1988, Saunders opened the world’s first “computer launderette” – a proto-cyber cafe – and launched a desktop publishing house where you could use computers to publish your own work. It was not a success. Most of the other quixotic schemes that he had around this time were never realised, except one, a restaurant called The World Food Cafe, which served vegetarian food from around the world (inspired by Saunders’ love of restaurant crawls where he would eat starters in one restaurant, mains in another and dessert at a third).

Friends attribute the happiness Saunders suddenly found in the 1990s to two events. First, he fell in love with a woman named Anja Dashwood, with whom he collaborated and lived, in the flat above Neal’s Yard, for the rest of his life. The second was his discovery of MDMA. Finding that it relieved his depression, Saunders began researching the drug in his typically obsessive way. His commitment to understanding MDMA would find him turning up to drum’n’bass raves, nervously looming over a baffled crowd of people a third of his age, who eventually adopted him as their own. “I experienced a feeling of belonging to the group, a kind of uplifting religious experience of unity that I have only felt once before, when I was part of a community [Christiania] that was threatened with closure,” he later wrote. Saunders combined all his research, including a thorough scientific analysis of every single street pill he came across, into a book published in 1993 called E For Ecstasy. Saunders’ website ecstasy.org would become as canonical to the 90s counterculture as Alternative London had been for the 70s; his acolytes called him the new Timothy Leary.

Then, a week after he turned 60, in February 1998, Saunders was dead. He had travelled to South Africa to research a new book on the use of psychoactive plants, and somewhere near the town of Kroonstad, the car he was being driven in skidded off the road. His funeral took place in a patch of forest in Surrey that he had bought in the 90s. It was perhaps the first time everyone from his many lives were in the same space: Saunders the hippy, Saunders the businessman and Saunders the guru. The abiding memory of everyone who attended is of the forest streaming with bubbles.

The businesses Saunders started – with the exception of the Dairy and Monmouth Coffee – have mirrored the fate of the counterculture itself. Some sold out and became big, others faded into obsolescence. Neal’s Yard Remedies is now owned by the Kindersley family (of Dorling Kindersley), while the wholefoods warehouse later became a branch of the multinational health food chain Holland & Barrett. The promise of freely available, high-quality information embodied by Alternative London seemed to have arrived in its ideal form with the early days of the internet, but is now fading, as a tiny number of infinitely rich tech companies dominate the space. Neal’s Yard, like Christiania, is a simulacrum of its former self, a restaurantified tourist trap, with only one business left that produces food, the S