At 10.30am on Monday 23 February 1874, the prize objects taken by British troops from the royal palace in Kumasi were put up for auction in the palaver hall of Cape Castle, on the Gold Coast. “The long centre table was covered as thickly as it could bear with jewellery and gold,” reported the Daily Telegraph. “On a side table stood the king’s plate. Against a broad screen hung swords and cartouche belts of leopard skin, and canes of huge silver heads, and calabashes bound in gold and silver, and embossed brass pans.”

Alongside the burning of the old Summer Palace in Beijing in 1860 and the Battle of Maqdala in Ethiopia in 1868, the sacking of Kumasi, during the third Anglo-Asante war, stands as one of the most infamous episodes in the history of British colonial plunder.

This week, on the 150th anniversary of the attack on the Asante, an important moment of acknowledgment and reflection is taking place as the Victoria and Albert Museum and the British Museum work in partnership with Manhyia Palace Museum, Kumasi, to return to Ghana some of this looted material.

While a long-term loan and not a full, legal repatriation of these wondrous examples of west African goldsmithing, this renewable cultural partnership offers a new paradigm for a broader sharing of contested colonial heritage, while existing laws preventing restitution remain in place. It might allow us to move beyond the limits of the Parthenon sculptures debate and think about a more equitable future for looted collections in so-called encyclopaedic, European museums.

What first attracted the British to the Asante empire – covering much of modern-day Ghana, Benin, Togo and Ivory Coast – was control of the extensive array of fortresses that dotted the Atlantic seaboard from where the Portuguese, Dutch, Danish, Swedish and then English dispatched enslaved Africans through the doors of no return to Caribbean and American plantations. After the 1807 abolition of the transatlantic slave trade, the empire’s focus turned to gold reserves and coastal trading routes. The Asante refused to succumb to the British protectorate and cede commercial rights.

In response, the British army launched a “punitive expedition” to exact reprisals against the Asante king (Asantehene) led by Major General Garnet Wolseley – the Kurtz of 19th-century British colonial violence, having seen action at Lucknow, the Summer Palace, the Zulu Wars and Khartoum. After burning towns and defeating Asante troops, the 42nd (Royal Highland) Regiment of Foot paved the way to enter Kumasi on 3 February. There Wolseley forced upon the Asante a grossly unequal treaty and exponential indemnity payments, and then appointed prize agents to gather the most valuable material from the palace to be sold at auction, with profits distributed among the troops.

Since Achilles was awarded the young girl Briseis as his slave after the sacking of Lyrnessus, and Agamemnon then enraged him by stealing her as loot, as chronicled in the Iliad, the fruits of battle have been a constant component of warfare across cultures and countries. Indeed, the very word “loot” is of Bengali origin. And as the British-Ghanaian philosopher Kwame Anthony Appiah has noted, the Epic of Sundiata, the most celebrated work of African oral literature – dating to the 13th century and telling of the establishment of the Mali empire – is also a story of war spoils.

The British perfected and codified the practice during the heyday of imperial expansion and, as curator Patrick Watt writes: “The organised taking of property by the British state was viewed by soldiers as legitimate practice at the end of [the] conflict.” This was very different, you see, from simply stealing. Captain Henry Brackenbury found that during the brief occupation of Kumasi “the troops refrained, with the most admirable self-control, from spoliation or plunder”. The court regalia, ceremonial swords, gold and silver looted from the royal palace were regarded as acquired entirely legitimately – according to the norms of war – by the War Office.

As the soldiers returned to Britain, the spoils began to make their way into auction houses and, in April 1874, the jeweller Garrard & Co took showrooms in London’s Haymarket to put on display “the collection of curiosities from the Gold Coast”. The expert skill of the Asante goldsmiths in hand-casting, rather than hammering the gold, astonished the London trade. “The English jewellers are not above owning that they may take some hints in casting from the Ashante workmen,” the Globe patronisingly reported, “some of whose designs are clever enough to baffle their conjectures as to how they were executed”.

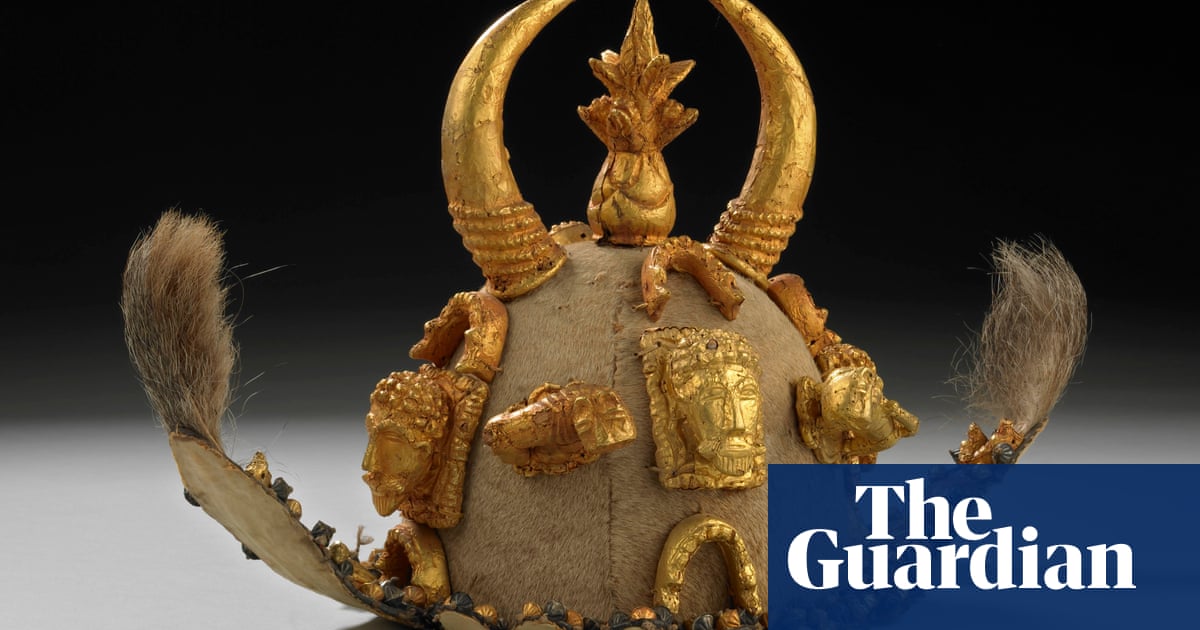

It was this artistry and craftsmanship which led the South Kensington Museum (as the V&A used to be called) to acquire 13 pieces of Asante court regalia from the Garrard auction, and display them as exemplars of the royal goldsmiths’ expert technique and an inspiration for British designers. So into the collection came a stunning, pure gold peace-pipe (Abua); three cast gold soul-washers’ badges; seven sections of sheet-gold ornament; a silver straining spoon; and a pair of silver anklets. Other material, including “two complete masks of gold”, were acquired by the British Museum, the Wallace Collection, and the royal household.

Gold regalia of enormous cultural, historical and spiritual significance to the Asante people, objects which were invested with the spirits of former kings and decorated with a complex visual lexicon, were put on display either as interesting examples of skilled metalwork or as spoils of imperial prowess. The Asante loot proved a star item at the 1886 Colonial and Indian Exhibition and, again, in the Gold Coast pavilion at the 1924 British Empire Exhibition at Wembley. Toymakers spied a commercial opportunity, producing thousands of small, gold-painted cast stools branded with the words “Ashanti stool, Wembley 1924”.

After Ghana’s independence in 1957, and the “winds of change” sweeping post-colonial Africa, the settled status of the Kumasi collection came under renewed scrutiny. The 1969 Pan-African Cultural Manifesto made a compelling case for repatriation: “The preservation of culture prevented the African peoples from becoming peoples without a soul and without a history … For this reason, Africa takes such care and attaches such value to the recovery of its cultural heritage, to the defence of its personality, and to the flourishing of new branches of its culture.” In 1974, on the centenary of the Kumasi sacking, the Asantehene made a formal request for the return of the gold regalia.

But, as has been well-documented, both the British Museum and the V&A are prevented by statute from returning items in their collection unless for highly specified reasons. These rulings do not apply to Nazi-era loot stolen from Jewish families, leading many African commentators to question why parliamentarians changed the law for those objects and not others.

Now, after 50 years of stalemate, thanks to the creative leadership of the Asantehene, Otumfuo Nana Osei Tutu II, we have the breakthrough which allows the regalia to return to Kumasi. Quite understandably, the government of Ghana has not ceded its official restitution requests, but this cultural partnership will see an important display of this sumptuous goldwork, reuniting collections so long divided, and allow for new scholarship, interpretation and conservation. This is not about reparative justice for the colonial past, but knowledge sharing and collaboration far beyond transactional loans.

In time, we hope to fill the gap left by the golden peace pipes and soul-washers’ badges with a new commission by a contemporary maker, honouring the incredible expertise – and contemporary design relevance – of Asantehene goldsmithing. Because alongside the colonial history and spiritual immanence, this also remains a story of aesthetics, craftsmanship and making.

It is also a continuing conversation about cultural exchange between Ghana and Britain. For the royal collections which the British troops ransacked in 1874 included books in many languages, European clocks and silver plates, Moorish handicraft and Persian carpets. “Yes, some of this was war booty,” writes Appiah of the Asante riches, “but what’s striking is that the Asantehene was evidently impressed by what he’d heard about the British Museum, and set out to create a notably cosmopolitan collection.” The looted royal holdings were, in fact, partly based around an Enlightenment ideal of British museums – which themselves are now, finally, seeking to return some of those very items in a new spirit of partnership and cultural exchange.

Legacy of plunder

Benin bronzes In 1897, the British sent a ‘punitive expedition’ of 1200 troops to Benin City to depose the Oba by force and take over the Edo Kingdom. British troops occupied and ransacked the royal palace, looting between 3000 and 5000 objects of immense cultural value from the palace compounds and other sites. Benin bronzes can be found across multiple UK museums, regimental museums and private collections.

Old Summer Palace, Beijing Also known as Yuanmingyuan, this amazing complex was looted and burnt down by French and British troops in 1860 during the Second Opium War. In 2006 Unesco estimated that about 1.6 million Chinese relics were in the possession of 47 museums worldwide.

Maqdala, Ethiopia An expeditionary campaign led by Sir Robert Napier against Tewodros II in 1868 led to the plundering of the Abyssinian Emperor’s fortress, partly overseen by curators. The UK Government acquired the spoils and distributed them to the V&A, British Museum and others, despite chancellor of the exchequer William Gladstone urging their return as soon as possible.

Recent Returns from UK Museums

National Museum Scotland has returned the House of Ni’isjoohl Memorial Pole to the Nisga’a people of Nass Valley, British Columbia

Royal Albert Memorial Museum and Art Gallery, Exeter has returned sacred regalia (including a buckskin shirt, pair of leggings, a knife with feather bundle, two beaded bags and a horsewhip) to the Siksika Nation in Canada

Manchester Museum has returned 174 cultural heritage items (including a group of dolls made from shells) to the Aboriginal Anindilyakwa community of Australia’s Northern Territory