Afew years ago, I walked into a large central London bookstore to find a book I’d written, planning to sign a few copies before its imminent publication (as authors are often encouraged to do). The book was about money – as both title and jacket copy made abundantly clear – and yet the bookseller I approached to ask where I might find copies informed me he’d placed them in… race studies. When I challenged him on that categorisation, he grew defensive, while one of his colleagues standing nearby visibly cringed. Over time, I grew to see the encounter as so on the nose as to render it absurd, almost comical – a perfect allegory for how the book industry views Black writers and yet so ludicrous that I considered it anomalous. Imagine my surprise then, when reading Percival Everett’s novel Erasure a few months ago, only to find that exact scenario playing out beat for beat.

Everett is as prolific as his work is uncategorisable, the author of more than 30 books, including 2022’s Booker-shortlisted The Trees. His previous novels have included allegorical zombie horror and a sort of spy caper, while his forthcoming novel, James, is a retelling of the Adventures of Huckleberry Finn through the eyes of enslaved Jim. Now Erasure, published in 2001 and widely regarded as one of his finest novels, has been adapted for the screen by journalist turned screenwriter Cord Jefferson. The result is American Fiction, a biting satire that takes aim at the publishing and media industry’s endless appetite for stereotypically “Black” narratives – or as one character bluntly states: “white publishers fiending Black trauma porn”.

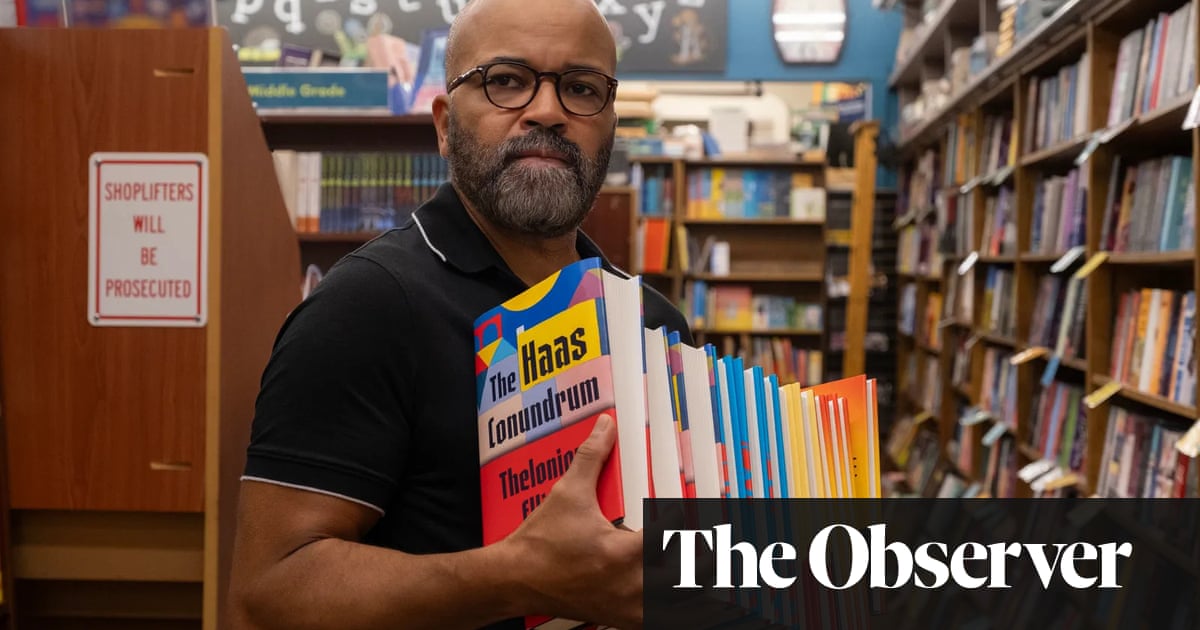

It follows novelist Thelonious “Monk” Ellison (played superbly by a grouchy but lovable Jeffrey Wright), who, frustrated by the publishing world’s elevation of stereotypical “hood lit” tropes over his own rather more high-minded literary efforts, decides in a Puckish moment of mischief to write a novel crammed with as many stereotypically “ghetto” tropes as possible. It is intended as parody, a middle finger to an industry that maddens him – but to his dismay, the ostensibly progressive white publishing world takes the novel at face value and he winds up with an astronomically large book advance. That Monk submitted the novel under a pseudonym only further complicates matters, and he is soon trapped between disgust at the publishing industry, at himself, and by the fact that he desperately needs the cash.

“One of the ways that white America chooses to receive work by Black artists is by focusing on the race of the creator,” Everett says when we speak about the reception his work often receives. “I would say that my addressing of race really has very little to do with that bogus category of race and more to do with the fact that I’m American – there is not a serious American novel that does not deal with race, and when race is not an issue in an American novel, that’s about race.” He describes the absence of Black people in the TV show Friends – set in one of the world’s most cosmopolitan cities – as “a commentary on how America would like to see itself”.

And though American Fiction looks set to be one of 2024’s buzziest movies, Erasure – experimental, deeply literary, often bleak – doesn’t immediately seem the most obvious material for screen adaptation, given current Hollywood appetites for big-budget IP blockbusters and easily franchise-able reboots. For Jefferson, however, the number of parallels between Erasure and his own experiences was compelling enough to prompt his first attempt at a feature-length screenplay. “Have you ever read a book that felt like it was written specifically for you?” he asks. “That’s how it felt when I read [Erasure].”

He is referring to Erasure’s professional themes, but also to its layered exploration of complicated family dynamics: sibling tensions, ailing parents, alienating father figures. “There was so much that related to my personal life that it just started to feel eerie after a while.” In fact, when Jefferson first began writing for TV nearly a decade ago, he felt the need to lay firm ground rules with his newly acquired reps, telling them: “If you only send me out for ‘Black’ shows, I will fire you. Because I’m sure that’s not how you treat your white clients – I’m sure you don’t just send [them] to things that fit their racial profile.” Having started his career as a journalist, he had grown tired of constantly being asked to cover what he referred to, in a viral 2014 essay, as “the racism beat”, and wanted to avoid a similar fate within television.

It’s interesting that American Fiction’s version of Monk’s parody novel opts to stay faithful to the style of literature originally satirised by Erasure, given publishing appetites for that sort of hood lit (1996’s Push by Sapphire is a clear reference here) have largely waned in the 20-odd years since Everett’s novel was published. Still, given the literary establishment has moved on to equally restrictive modes of engagement with Black writers, frequently pressuring them to foreground their identities or racial trauma, that anachronism doesn’t particularly undercut the film’s message.

And American Fiction otherwise manages to capture the myriad anxieties and minor indignities of the writer’s life with hilarious accuracy: a misspelled name tag at a sparsely attended literary festival panel feels all too familiar; I recognise, too, Monk’s resentment towards the smug and (of course) undeserving anointed few who’ve chosen to “play the game”. In his case, that is the pandering Sintara Golden (played by Rae), who veers between slyly obsequious and cynically self-aware, and whose runaway bestseller We’s Lives in da Ghetto provides the template for Monk’s own ghetto fanfic.

In adapting Everett’s darkly funny text, Jefferson opts to amp up the comedy, and he informs the audience at a screening I attend that he wants them to laugh, specifically giving permission to the white people in the audience to laugh at his treatment of race. Why was that so important to him? “I remember going to see Amistad [Steven Spielberg’s 1997 historical drama of enslaved people] in the theatre with my family in Tucson, Arizona.” This is where Jefferson grew up, by his telling in an area with very few other Black or biracial people. “The theatre was nearly empty. And I enjoyed the movie, I thought it was good, but we left and I thought… ‘Are we the people who need to see this movie?’”

In his own movie, comedy is employed as a Trojan horse, allowing Jefferson to make serious points about race and how our culture metabolises it while avoiding being a scold. It’s a smart approach, one that lets American Fiction sidestep the white fatigue with race discourse I sensed creeping in almost immediately after the histrionic self-flagellation of 2020. Jefferson cites other race satires, including Robert Townsend’s Hollywood Shuffle and Spike Lee’s Bamboozled, as “spiritual predecessors” to his own. “I wanted this movie to feel welcoming. This is a conversation that I wanted a lot of people to participate in.”

But does that impulse mean American Fiction risks becoming the very thing it is satirising – that is, stories about Black people angled towards the white gaze and which portray the Black experience solely in relation to white people? Especially since 2020, a tendency I’ve observed within my own home turf of publishing and journalism is that the type of Black-authored work (the largely white) industry gatekeepers favour frequently puts racism – and therefore white people – at or close to its centre, even if only as obstacles to Black self-realisation.

Jefferson, too, seems conscious of this potential hazard, well aware that the white-saviour narratives long championed by Hollywood – enslaved people movies, or civil rights biopics – also often conversely provide absolution for white audiences, who can set themselves against the flagrant racism of, say, a Ku Klux Klan member burning a cross on a lawn, eliding the many subtler ways they themselves enact racism on a daily basis. As Monk’s literary agent observes early on: “White people think they want the truth but they don’t. They just want to feel absolved.”

“That was something I wanted to avoid,” Jefferson notes. “I didn’t want to make a movie ostensibly saying: ‘This is a movie about Black people’ and yet it centres whiteness in a very real way and shunts the Black characters to the side. It’s something that I thought about a lot.” Consequently, American Fiction is rich with irony and remains drolly self-aware throughout; at one point Monk drily remarks to the white editor who has acquired his book: “I’m sure white people on the Hamptons will delight in it.” It feels like a pointed commentary on how the movie of which he is unwittingly the star will itself be received, the snake-eating-its-tail nature of creating work that critiques white people in a post-George Floyd landscape.

American Fiction avoids that pitfall by broadening its scope far beyond the consequences of white liberal anxieties. Though much of the discourse around the film – much like the initial trailer released – has focused largely on its treatment of race, audiences may be surprised to find large parts of the film are a poignant study of a family in crisis, making clear that racism is not the defining pillar of Black identity. I imagine it has been strategically marketed thus, in the knowledge that white moviegoers may not be interested in a film they suspect is about something as quotidian as ordinary Black people experiencing quiet family drama – if indeed such a film would ever even be greenlit.

Monk’s relative privilege also allows for subtle commentary on intra-community class dynamics: a middle-class college professor, he is, alas, an incorrigible snob, and the depiction of low-income Black America he dreams up, one of “deadbeat dads, rappers, crack”, verges on the grotesque. It’s never clear how much of that is his own view and how much is him reflecting the culture’s prejudices back at it as part of his literary prank. Jefferson is clear, though, that this is not his own stance, pointing out that his film is not intended as criticism of the sort of Black art that Monk himself despises, so much as an effort to challenge its predominance.

“The first thing that Jeffrey [Wright] said when we met,” he says, “was: ‘I want to make sure that you don’t want to make some sort of respectability politics, “talented tenth”, Bill Cosby “pull up your pants” movie.’ It just made it even clearer that he was thinking about this film in the same way I was and that he was the exact person for Monk.” It’s a sentiment Everett echoes when discussing Erasure: “My contention was never that that kind of work is not art. My problem was that was the only thing available and it was viewed as representational of the African American experience, reducing it to one thing.”

With five Oscar nominations under its belt, along with a Bafta nomination for adapted screenplay and two Golden Globe nominations, it doesn’t feel like hyperbole to suggest that American Fiction feels like an instant modern classic. Outside of awards ceremonies, it seems destined to foster lively debate: already a handful of conservative commentators have claimed it as a victory for “anti-woke” narratives, though to me it seems much more closely aligned with conversations my distinctly “woke” peers and I have been having for years.

Even still, I’m left turning over a series of uncomfortable, complex questions long after the credits have rolled. Where does one draw the line between authenticity and pandering? Do I need to temper my disdain for Black authors who choose to “play the game”? How weird should I feel about how hard white people in that cinema were laughing? Each question invites two more and I land on a different answer most times. I suspect that’s exactly the film’s intention.

Otegha Uwagba’s most recent book is We Need to Talk About Money (Fourth Estate)