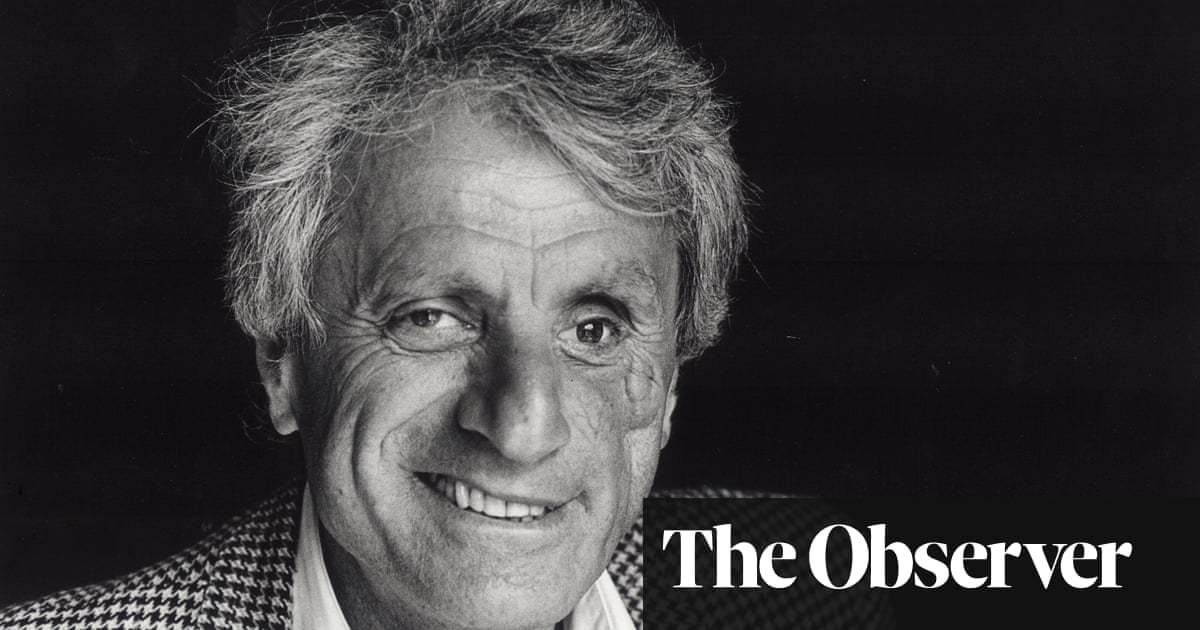

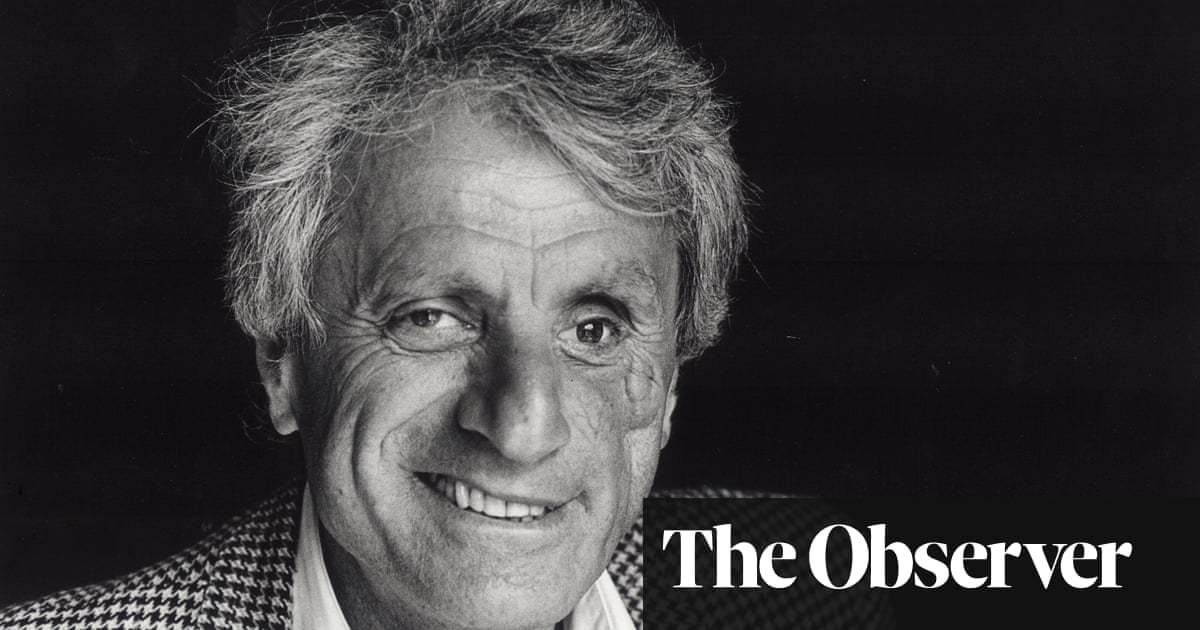

He was the high priest of 20th-century modernity, a founding father of electronic music, a pioneer of multi-faceted talent. Where others feared to tread Iannis Xenakis stepped, breaking the boundaries of sound, employing mathematical formulae – game theory included – to compose what had never been heard before.

No musician – or architect, for he was that too – was as steeped in the classics nor as avant garde nor as quintessentially Greek.

And yet it has taken more than 20 years since his death in Paris, the place to which he fled after narrowly surviving a British tank shell in the clashes that preceded Greece’s brutal civil war, for Xenakis to be properly feted in the country of his origin.

“Few cultural figures were as important in the second half of the century,” said Katerina Gregos, the artistic director of the National Museum of Contemporary Art in Athens (EMST). “Xenakis was not just a polymath, a visionary, a true cosmopolitan, he was a mathematician, civil engineer, architect, author, music theorist, composer and draftsman, a Renaissance man from the future.”

Gregos, one of Europe’s most established curators before she assumed the helm of the flagship museum, has long wanted Greece to pay tribute to an artist who decades earlier had been admitted into France’s Academy of Fine Arts and decorated with the French Legion of Honour. Xenakis, who for years was an apprentice under the French modernist architect, Le Corbusier, was credited with designing the Philips Pavilion, constructed in 1958 for the Brussels expo and inspired by one of his first iconic compositions “Metastaseis”.

“It had been a dream,” she told the Observer. “Elsewhere he had been celebrated far and wide, here fitting tribute had never been paid. It was a glaring omission of the Greek state towards someone of such enormous stature.”

The fruit of the endeavour has resulted in his oeuvre being exhibited as never before. “What we have done in collaboration with the Musée de la Musique – Philharmonie de Paris and the Centre for Contemporary Research of the Athens Conservatoire (CMRC) is finally host the first major comprehensive presentation of his work,” Gregos explained. “There had been shows and concerts here and there, but this is the first time he has been acknowledged on an institutional level in Greece.”

The re-embrace has seen record numbers flock to EMST, a concrete edifice on a busy boulevard beneath the Acropolis, with hundreds daily visiting the exhibition dedicated to Xenakis’ troubled relationship with Greece, drawn from the archives of the CMRC which the composer co-founded. “Finally a museum is doing what should have been done so long ago,” smiled Eleni Katsarou, 34, an electronic music producer marvelling at the UPIC, a makeshift “computerised musical composition” system devised by the artist to translate images into notes. “He was such a force, so ahead of his time, unique. It’s mind-blowing to think he predicted how we’d produce music, how composers would one day be computer programmers synthesising sound.”

The extraordinary time it has taken for Greece to allow Xenakis back into the fold is, say aficionados, all the more incredible given his influence internationally. The Romanian-born Greek inspired the likes of Lou Reed, Ryuichi Sakamoto, the Japanese avant gardist, and Frank Zappa with his groundbreaking techniques and innovative use of mathematics still felt as much in the world of conservatory-trained composers as experimental electronic music.

“You find him in some of the most unexpected corners of electronic music,” said Colin Hacklander, one half of the Berlin-based sound artist duo, Labour. “His ability to harness the random, the chaotic, the unpredictable into formalised composition has been greatly inspiring for us and I think for all advent gardists.”

Hacklander, like other admirers, believes Xenakis’ experience of conflict resonates in the “complex noise” of works that often burst with sound. “You can hear the mass movement of people, the bursts of gunfire in the music,” the American composer said. “It was a totally unorthodox approach. He was an outsider to the musical establishment, constantly questioning himself.”

The stuff of heroic novels, Xenakis’ life story mirrors the turbulent path of modern Greek history and partly explains why in his native land he was left unacknowledged for so long. A privileged education on the Argo-Saronic island of Spetses, in a boarding school whose alumni included the late King Constantine, was followed by events that would mark him for ever: Nazi occupation and the bloodshed that preceded the outbreak of civil war.

After signing up with the resistance and losing his left eye in the violence that erupted in Athens in 1944, he was forced into hiding before fleeing abroad – a decision that filled the composer with guilt and lingering nostalgia. Music was the creative force through which, he would later say, he could “do something important to regain the right to live”. As divisions in Greece intensified – a schism between left and right still evident today – all his radicalism and free spirit went into it.

“He was part of a generation of politically persecuted intellectuals who exemplified this political dichotomy in society,” Gregos said. “Avant garde artists who had left to go abroad were not acknowledged. The fact that Xenakis was a former communist, sentenced to death by a military tribunal in absentia, didn’t help.”

When he did return – after being pardoned following the collapse of military rule – it was to not only to savour what he had missed but to stage the “Mycenae polytope”, a light and sound spectacle of such magnitude it involved the army, a children’s choir, professional performers, shepherds and hundreds of sheep. The performance, held on a single night in September 1978, in the rolling hills outside Mycenae is viewed as a precursor of multimedia installations now a regular feature in the art world. “For far too long the avant garde legacy of the Greek diaspora has been marginalised,” sighed Gregos. “It’s our mission to highlight it.”