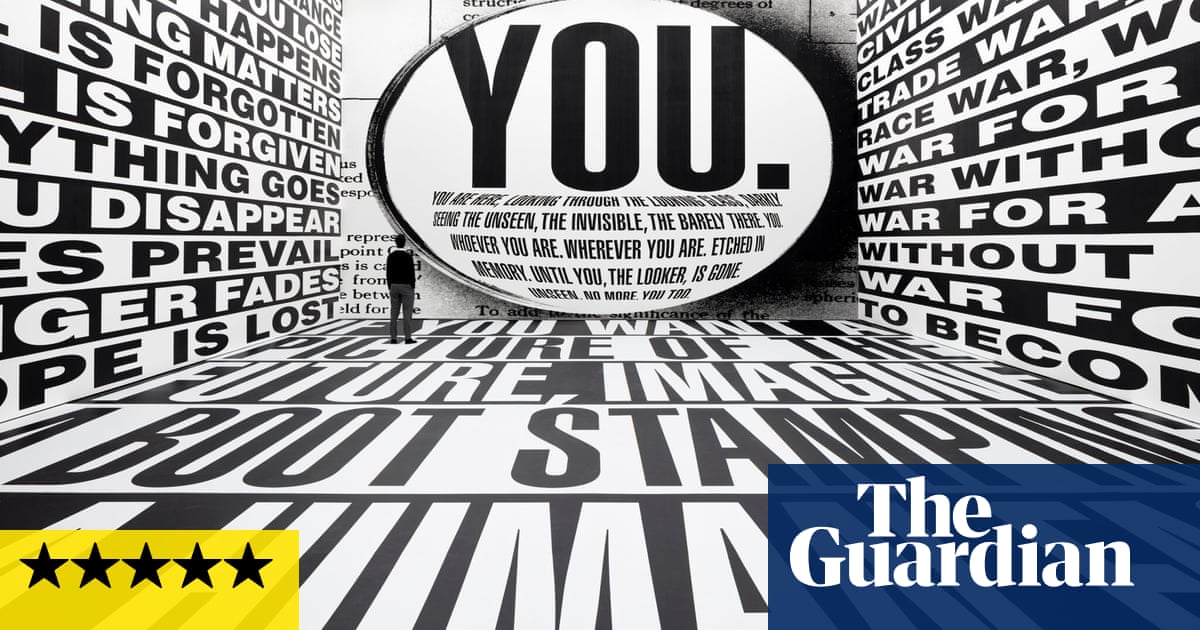

Hello? Hello? Sorry. Ker-ching! Ker-ching! Sorry again. A metronome beat is becoming a machine-gun burst of hammering and clanging, interspersed with Big Ben chimes and distant echoes from other rooms. This is Barbara Kruger’s Thinking of You. I Mean Me. I Mean You, at the Serpentine. The title is anything but an equivocation. This is a show filled with switchbacks, reversals, reworkings and visual and verbal plays, as Kruger, nearing 80, lifts us up and grinds us down, second to second, minute to minute, through room after room of a show that refuses to quieten down into a conventional retrospective.

Greeting the viewer immediately on arrival at the London gallery, this onslaught – a mix of specially recorded audio snippets and sound leakage from the installations and individual screens that fill the galleries – adds to what is already a cacophonous riot of word and image. Often the words are the images, scrolling down the walls and launching from the screens. So many words, too many to try to grasp as they roll by. They doomscroll us as we doomscroll them, taking up all the room in our already overstuffed heads. So many words, so much catching up to do. the words fill screens, cross the floors and rage around the walls.

Kruger’s stream-of-consciousness routines can feel like a speed-freak comedy act, or a mix of deranged stump-speeches, parodic university lectures, and the kind of statements artists would make if they harboured messianic dreams of world domination. Kruger came to fame in the 1980s, the child of a cut-and-paste analogue culture, but her art has a cumulative effect and increasing range. Everything in her art is and always was political. “Our people are better than your people,” reads one large panel. “More intelligent, more powerful, more beautiful, and cleaner. We are good and you are evil. God is on our side. Our shit doesn’t stink and we invented everything.”

This is Untitled (Our People are Better Than Your People), from 1994, a premonition of the Orwellian language of Trumpspeak, which she returns to in her three-screen Untitled (No Comment), from 2020. Amid the hysterical laughter accompanying pouting, out-of-focus selfies (only the lipsticked mouths stay in focus), and the Instagram pics of pussycats in toilet bowls and Lady Gaga’s manipulated visage, Kruger asks, “What do you want from me? What do you want me to want from you?”

She then goes on to quote French writer Voltaire, “Those who make you believe absurdities can make you commit atrocities”, then Austrian writer Karl Kraus: ‘The secret of the demagogue is to make himself as stupid as his audience so that they believe they’re as clever as he is.” Now here come some stupid hair plaits and designer beards, with a guy playing an accordion whose squeezebox bears the words: “Ghosted, Trolled, Ripped, Ranted, Rented, Flamed, Screwed and Owned.”

Phew. No Comment is filled with verbal riffs, sight gags, non-sequiters and stuff found on the internet. And more cats, as well as a voice that sounds like former US secretary of state Henry Kissinger. At one point the words flood three walls in a surging tide. “This is about a world in shambles,” Kruger says. Or rather the words say, if they are Kruger’s. She’s in there somewhere, along with Kraus and Voltaire and US rapper Kendrick Lamar, and an acrobatic contortionist tying herself in knots.

“I shop therefore I am.” Who said that? Was it René Descartes? Kruger’s consumerist play on the 17th-century French philosopher’s dictum first appeared in the 1980s, a time when, for most, the internet hadn’t happened yet. Since then our brains have been scrambled. In 2007, Kruger’s bold statements, white on red, black on white, filled Selfridges department stores and appeared in their winter sale advertising campaign. They were seen on TV and appeared on posters, becoming part of the background noise that accompanies our lives. But the background has now become the foreground, mediating our lives as we stare at TikTok while we wander into the traffic.

A 1989 poster made for the Women’s March on Washington, in support of legal abortion, depicted a woman’s head, half in positive, half in negative, and declared: “Your Body is a Battleground.” It became a rallying cry. Here, it is reworked on a large digital screen, the words flipping to assert that “My Coffee is a Motorboat”, then morphing into “Your Will is Bought and Sold”, and “Your Humility is Bullshit”. It goes on to a murderous conclusion.

Beginning with pre-digital paste-ups and collisions of word and image, Kruger has extended her range while staying absolutely true to herself. She has always been pithy and sardonic, sometimes obvious and sometimes opaque and abstruse, playing games with the methods and manners of mass communication and often investing phrases with calculated menace and subterfuge. There’s horror in there as well as a desire to unpick and to analyse.

When she was young she tried to be a poet and gave it up, only for a kind of poetry to sneak back in. Her recent Untitled (The Work Is About) – in which the titular phrase recurs in a litany of statements of intent, sliding up the wall like a movie’s end credits – began its life in a 1979 magazine article under the title Job Description.

The Work Is About mentions “the punishment of binaries, sex and perpetual churn … audience and the scrutiny of women, spectacle and the enveloped viewer … race and damage and brutality … privilege and the tyranny of exclusion … narrative and the gathering of incidents … dreams and the sliding of meaning … dogma and bloated pieties … money and the velocity of power”. It goes on like this for over five minutes. A stenographer could hardly keep up.

Kruger’s aphorisms lodged in the mind from the start and stayed there, along with all the other junk that already fills our heads, ready to be trotted out in the ticker tape of ready-made catchphrases, commonplaces, advertising slogans and oft-repeated punchlines that provide the junk food of everyday conversation and which pass for thought. It is as if we were speaking in slogans, delivered in Futura Bold Oblique and Helvetica Ultra Compressed. With a self-evident, sans serif finality that brooks no argument and eschews all ambiguity, Kruger’s words come at us like orders, subtle as a brick in the face. But words are tricky, and they slip and slide.

As a succession of one-liners, incontrovertible truths, lies, misdirections, fallacies and opaque pronouncements, Kruger’s work unravels then reconfigures itself as we watch and we read. Much of the time it is as if she were replacing our own inner commentaries with hers. To begin with, her art felt fun but limited – and, although she is still reworking the same territory, she’s been deepening the game all the while. There’s no end to it. Kruger’s words are timebombs, prophetic detonations that never stop.

Barbara Kruger: Thinking of You. I Mean Me. I Mean You is at the Serpentine South Gallery, London, 1 February until 17 March.