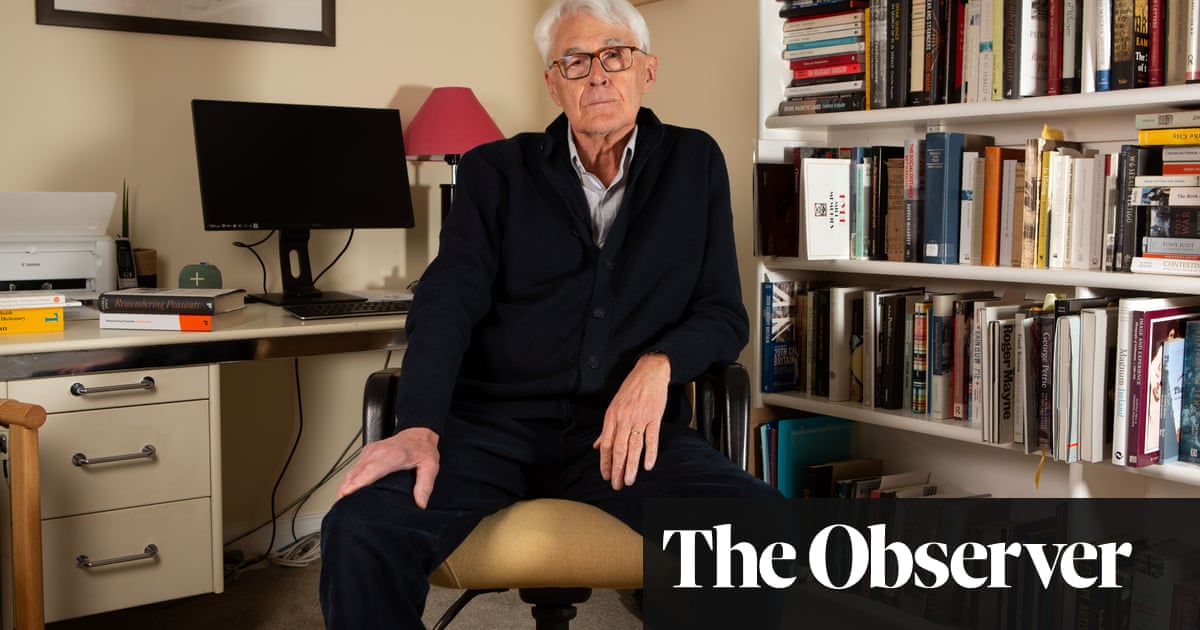

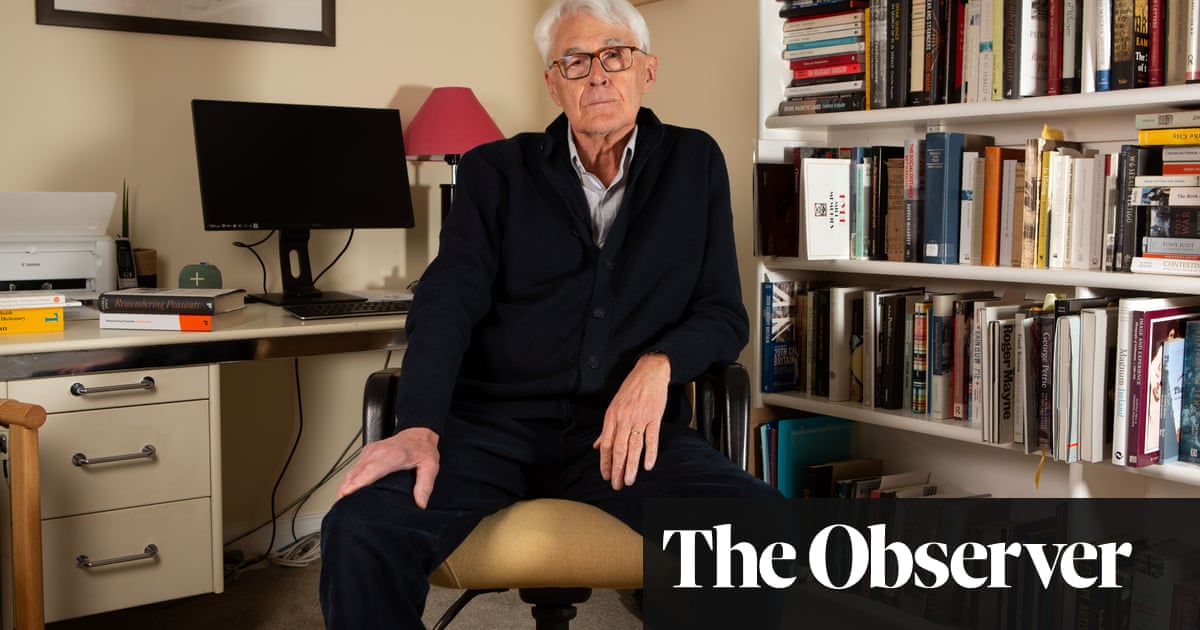

Patrick Joyce is emeritus professor of history at the University of Manchester and one of the leading social historians of his generation. The illustrious referees for his first academic job in the 1970s were Eric Hobsbawm and EP Thompson. In his 70s, Joyce has found a new non-academic audience combining memoir and history. His new book, Remembering Peasants: A Personal History of a Vanished World, follows in the footsteps of Going to My Father’s House, which looked at themes of emigration, home and war. Joyce lives in Broadbottom, a former mill village on the edge of the Peak District.

In your book, you describe the world of European peasants as one that is disappearing. In France, which you write was “once the greatest peasant country in Europe”, only about 3% of the population now work in agriculture. What made you embark on this project of remembrance and commemoration?

It came partly out of the sense of respect for one’s own – my grandparents lived this life, and my parents were born into this world before emigrating from Ireland to England. But also out of a recognition that the history of peasants is one of their silence or being silenced. People speak on their behalf; they very seldom speak on their own. These people have been misunderstood and degraded in so many historical accounts. And they’ve also been falsely glorified by 20th-century communism, fascism and nationalism as some kind of elemental force in the universe. I was an insider to the peasant world. I knew something about it.

What can we learn from their world, if we take the time to try to understand it?

There is a way of life there that is of extraordinary value to us. These are people who know they cannot bend the world to their will. People who recognise the limits of their knowledge. Peasants have an instinctive recognition that things are finite, that we cannot drive forever towards unlimited increase. They are outside the capitalist world in that way. They live within a horizon of necessity that we no longer inhabit, although the environmental crisis tells us we may have to inhabit it again. They’re survivors, as we may have to learn to be.

You also describe being struck by how, in peasant communities, there is an underlying sense of solidarity, one of people and nature both.

We often want to stand outside nature and admire it; we want to be enchanted by it. For peasants, nature is not a beautiful thing; it harbours evil, unpredictable forces. You have to show your solidarity with it – and that includes the people and animals alongside you and the system you are bound into. It’s about the creation of order in a world that is deeply subject to disorder, because of the vagaries of the seasons, famine and the social cleavages that sometimes threatened to tear peasant societies apart. This is a deeply binding order. In the book I dialogue with the spirit of Seamus Heaney on this – he talks about the origin of the word religion in the Latin, religare, meaning to bind. The natural, spiritual and divine constantly overlap in peasant culture and represent a sort of binding to the universe.

What do you make of the current farmers’ protests in Europe? Are these the successors to the old peasants, also misunderstood and condescended to?

I wouldn’t want to glorify them, because in south-east Poland, for example – where I visited last year – these are the people behind Law and Justice [the radical right nationalist party]. But then again, that was because that party gave them some respect, so the left has lessons to learn. But the modern marginalised are so often the migrants, and so often they are modern peasants – the Moroccans, Albanians and Tunisians who come to work the land in Europe and are frequently exploited. As migrants they live on the periphery. It goes through the same cycle as my parents.

Like Going to My Father’s House, the book includes very moving elements of memoir. Has combining the personal and the historical opened up new avenues for you, making your work more accessible?

I’ve spent my life as an academic, but now I seem to have a second career in my late 70s. It’s weird, but good, exhausting though as one ages. Here I am doing an interview with the august Observer! I always felt I could write, when I got into the more detailed phase of the historical work, but in writing this and Going to My Father’s House, I let certain guiding spirits take over, like WG Sebald in the latter. The influence might be at several removes but it’s there, partly in the melancholy as well.

Do you think of yourself as a melancholy writer?

The melancholic is a literary mode which may or may not involve melancholy of mind. I keep busy and am incubating a new book on the history of our sense of time and changing meanings of the past since 1945. What else but sadness can one feel when looking at the 20th century?

What was the first book you fell in love with?

I wasn’t brought up in a house with books, so it was comics mainly. There were a few books. You read the stuff of the day, what was in the public library – John Steinbeck, John O’Hara. One thing I did love as a child was the irrepressible Nigel Molesworth and Down With Skool! I relished Molesworth and the soppy Fotherington-Tomas – “Hullo clouds, hullo sky!” Molesworth was a perpetual schoolboy in rebellion. I loved that.

What are you reading now?

I’ve just finished Dermot Healy’s book A Goat Song, which I was deeply impressed by. I love that generation of Irish writers, John McGahern among them. Healy’s work is enormously ambitious. He is one of the greatest Irish novelists, though unacknowledged as such. I’m also reading Annie Ernaux’s story of her father: A Man’s Place. Annie Ernaux… there’s another way of doing the personal and the historical.

Remembering Peasants: A Personal History of a Vanished World by Patrick Joyce is published by Allen Lane (£25). To support the Guardian and Observer order your copy at guardianbookshop.com. Delivery charges may apply