The postwar relationship between Germany and the US was broadly stable and strong until the advent of the Trump presidency. Huge uncertainty has plagued the relationship since 2017, and it has still not fully stabilized following the departure of the great disruptor, Donald Trump, from the White House in 2021.

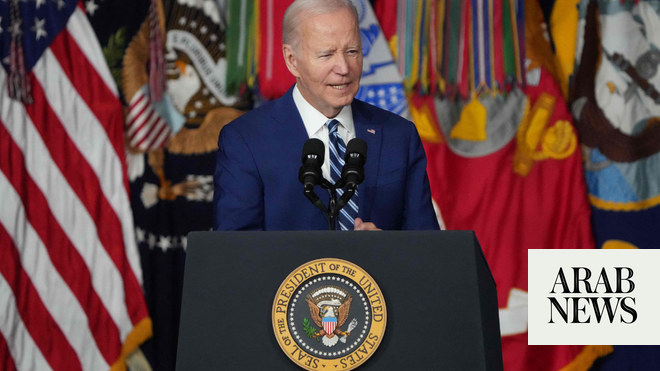

US President Joe Biden and German Chancellor Olaf Scholz are certainly much more like-minded partners than were Trump and Angela Merkel, who might have had the worst relationship, by some margin, of any of their predecessors in modern history.

This even applies if you consider the bilateral tensions that arose over the 2003 Iraq War, which resulted in a significant schism in the transatlantic alliance when Chancellor Gerhard Schroder opposed President George W. Bush’s decision to topple Saddam Hussein’s regime.

However, even Biden and Scholz have some key differences, despite their apparently similar political and personal dispositions. On this issue of Ukraine, for instance, tensions have risen since the Russian invasion over the pace and scope of Western support to Kyiv. One example of this was the disagreement between the two leaders over whether to provide tanks.

The US administration also has significant concerns about Germany’s policy on China, given that Berlin has, at least since Merkel’s time, been one of the primary advocates of Western economic engagement with Beijing. Scholz in 2022 became the first G7 leader to visit Beijing since the start of the pandemic, which was an indication of the level of importance Germany places on trade ties with China.

That long-standing German stance has come in for strong criticism, however, domestically and abroad. The perception that Scholz might be seeking to keep much of Merkel’s China policy intact has been widely condemned. The Obama-era US ambassador to NATO, Ivo Daalder, for example, warned that Germany could potentially be “headed for a collision” with the Biden team.

Yet another issue complicating bilateral ties is the US Inflation Reduction Act, a huge package of subsidies for clean tech, which poses a potentially major risk to the EU’s goal of remaining a preeminent global center for the green industrial revolution.

There is a growing sense in Europe that its edge in this “race” is imperiled. This has triggered a transatlantic row, and German Economy Minister Robert Habeck has highlighted the need for an intensified European “industrial policy that enables our companies to thrive in global competition, especially through technological leadership.”

Challenging as these differences can sometimes be, Biden and Scholz have nonetheless sought to rebuild the US-German relationship, which is very important to both countries.

For the US president, the importance of Berlin has only increased in the post-Brexit landscape. Equally, Scholz — who had little foreign policy experience before becoming chancellor, having previously served as minister of finance, and minister of labor and social affairs — quickly acknowledged the importance of the US to Germany.

For the US president, the importance of Berlin has only increased in the post-Brexit landscape.

Andrew Hammond

Building on this foundation, there will be much for the two leaders to agree upon when they meet this coming week at the White House, including the importance of Biden’s strategic goal of reuniting the Western alliance following the divisions caused by the Trump presidency.

Both leaders agree on the importance of closer cooperation on a range of challenges, including international security, promoting economic prosperity, and the threats posed by climate change.

Biden perceives the US-Germany relationship as key to this mission, because in the post-Brexit era he views Berlin as an increasingly important anchor point, perhaps alongside Paris, in the transatlantic relationship during a time of growing geopolitical flux.

There might also be some diplomatic upside from easing bilateral tensions over irritants such as the Inflation Reduction Act, to help accelerate the global clean-energy economy through secure, resilient supply chains and deeper cooperation in critical and emerging technologies.

Brussels and Washington are discussing an agreement on critical minerals that would allow companies based in Europe access to certain subsidies through the act, if they in turn provide some of the raw materials needed in the US for manufacturing processes. This would replicate a similar American deal with Japan.

At the same time, the US and EU are reportedly deep in negotiations on a so-called global arrangement on sustainable steel and aluminum. This is forestalling the reintroduction of US and EU tariffs on steel and aluminum, which were frozen by a provisional bilateral agreement in October 2021 that suspended measures introduced in 2018 when Trump imposed tariffs on European imports.

If such an ambitious agreement eventually is reached it would potentially create the political space for Washington and Brussels also to try to reach compromises on the EU’s recently introduced Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism. There is no agreement yet on how American steel companies will deal with this new policy, whereby European importers have to pay duties corresponding to the cost of emissions generated during production.

Moreover, Biden has dialed down the rhetoric, in public, on several long-standing irritants in the relationship between the US and Germany that Trump had emphasized, especially relating to trade and defense spending.

On trade, for example, Trump described Germany as “very bad” because of its significant trade surplus, with exports outweighing imports. He was also vocal in his criticism of Berlin’s failure to spend 2 percent of its gross domestic product on defense, a key NATO goal. Germany might now meet this target, as a result of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Taking all of this together, it is clear that there is potentially much more upside in the US-German partnership under Biden and Scholz, especially if new accords can be reached in areas such as critical minerals, steel and aluminum.

Yet several underlying uncertainties remain — and the relationship could yet go into diplomatic free fall if Trump wins a second term in office come November.

• Andrew Hammond is an associate at LSE IDEAS at the London School of Economics.