Officials at Cern, home to the Large Hadron Collider near Geneva, are pressing ahead with plans for a new machine that would be at least three times bigger than the existing particle accelerator.

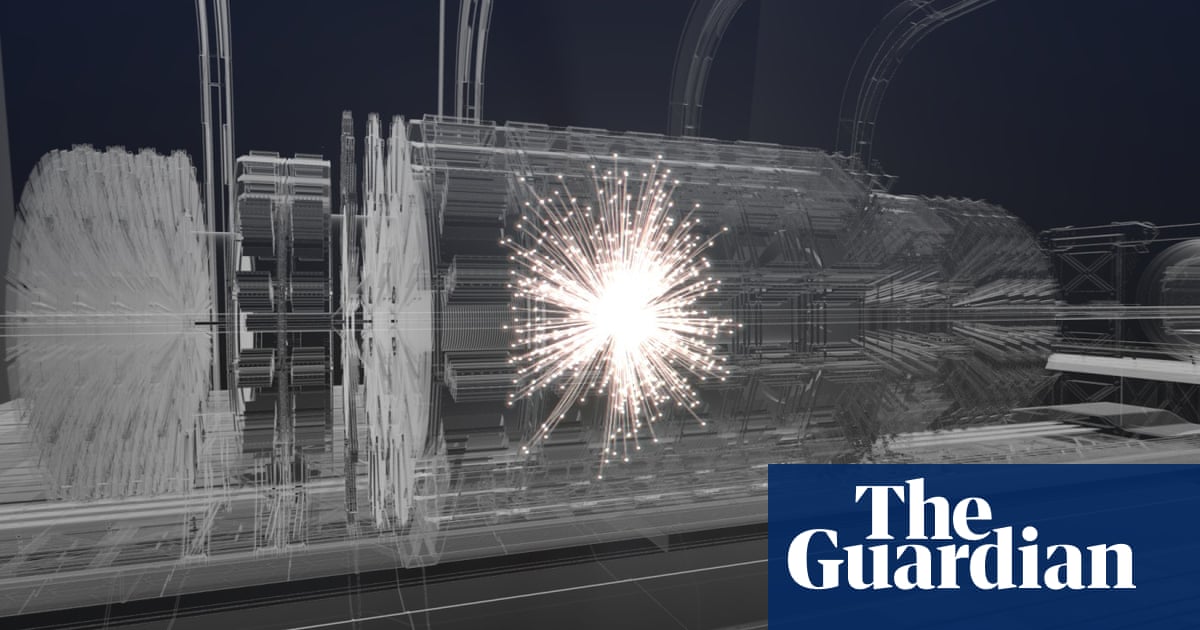

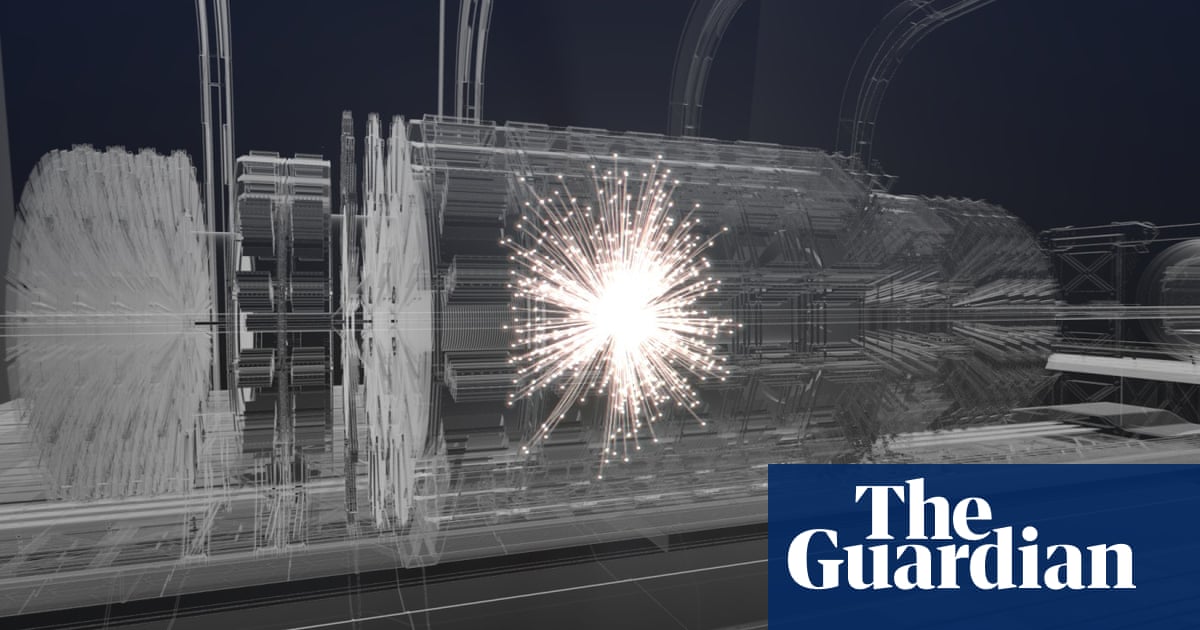

The Large Hadron Collider, built inside a 27km circular tunnel beneath the Swiss-French countryside, smashes together protons and other subatomic particles at close to the speed of light to recreate the conditions that existed fractions of a second after the big bang.

The machine, the world’s largest collider, was used in the discovery of the Higgs boson in 2012, nearly 50 years after the particle was proposed by Peter Higgs, the theoretical physicist at the University of Edinburgh, and several other researchers. The feat was honoured with the Nobel prize in physics the following year.

But since the discovery of the Higgs boson, the collider has not revealed any significant new physics that might shed light on some of the deepest mysteries of the universe, such as the nature of dark matter or dark energy, why matter dominates over antimatter, and whether reality is permeated with hidden extra dimensions.

Cern drew up plans for the next machine, the Future Circular Collider (FCC), in 2019. The €20bn (£17bn) machine would have a 91km circumference and aim to smash subatomic particles together at a maximum energy of 100 teraelectronvolts (TeV). The Large Hadron Collider achieves maximum energies of 14TeV.

The proposal has its critics, however. Sir David King, the UK’s former government chief scientific adviser, told the BBC that spending billions on the machine would be “reckless” when the world was facing such grave threats from the climate crisis.

On Friday, the Cern council discussed a midterm review of a feasibility study for the FCC. If the plans go ahead, the organisation would ask for approval in the next five years and hope to have the machine built and ready for operations in the 2040s when the LHC has completed its runs.

Prof Fabiola Gianotti, the director general of Cern, said: “If approved, the FCC would be the most powerful microscope ever built to study the laws of nature at the smallest scales and highest energies, with the goal of addressing some of the outstanding questions in today’s fundamental physics and our understanding of the universe.”

Tara Shears, a member of the LHCb experiment at the Large Hadron Collider, and professor of physics at the University of Liverpool, said: “The science case is really exciting. At the moment we’re carrying out a study to see if the machine is feasible. That should be finished in 2025, with a decision on the best way forward by 2028.

“It’s a next generation machine: bigger, faster, stronger, with the capability to reveal so much more detail about the fine details of the universe. It will reveal features of the Higgs and Higgs field that just can’t be studied at the Large Hadron Collider, and let us look for dark matter and test new physics ideas in new regimes.”

If the machine is approved it would be built in two stages. The first experiments would collide electrons and positrons while the second phase, earmarked for the 2070s, would slam protons into one another. Because of the extra radiation generated by the machine, it would need to sit twice as far underground as the Large Hadron Collider.

Dr Sabine Hossenfelder at the Munich Center for Mathematical Philosophy, said there was no evidence the FCC would reveal anything about dark matter or dark energy and was critical of the proposals.

“The truth is that the most likely thing such a machine would do is to just make better measurements of some constants in the standard model, and that’s it,” she said. “I do not think that the societal relevance is high enough to justify such a big investment.

“I fear that funding such an experiment will mean that a lot of smart people will waste their time on research that will not lead to any progress. The LHC had a good motivation. The FCC has not. Particle physicists have to accept that their time is over. This is the age of quantum physics.”

Prof Jon Butterworth, a member of the Atlas experiment at the Large Hadron Collider and a professor of physics at University College London, said the collider was a work in progress.

“This is about extending the frontier of human knowledge into the heart of matter and the fundamental forces, in part to see how fundamental they really are,” he added.