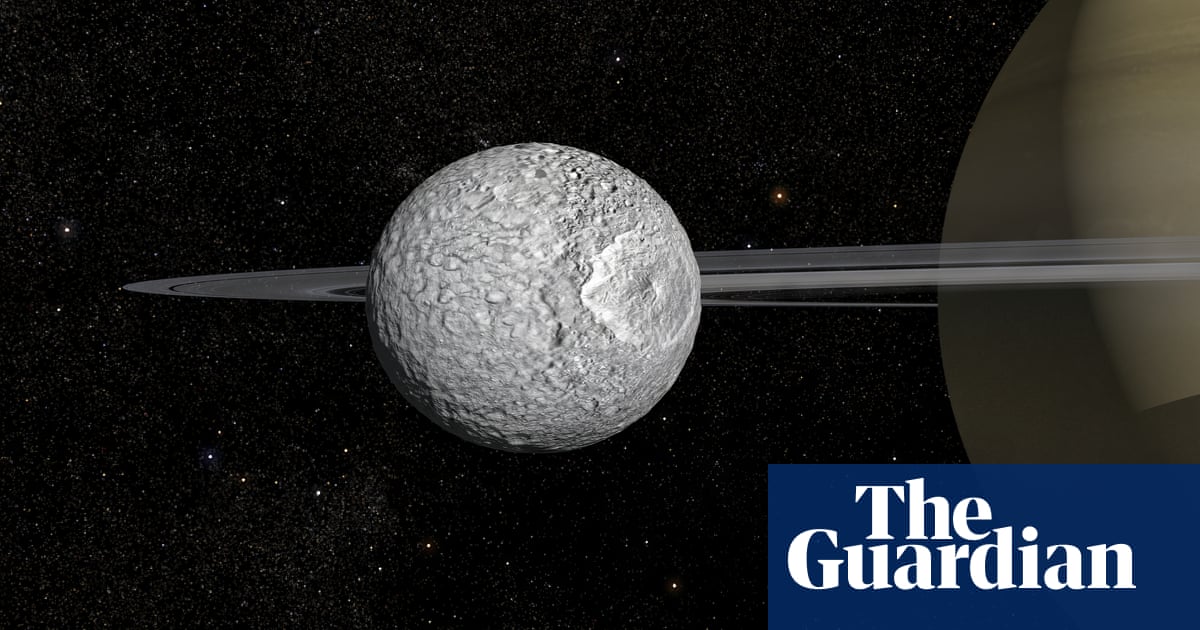

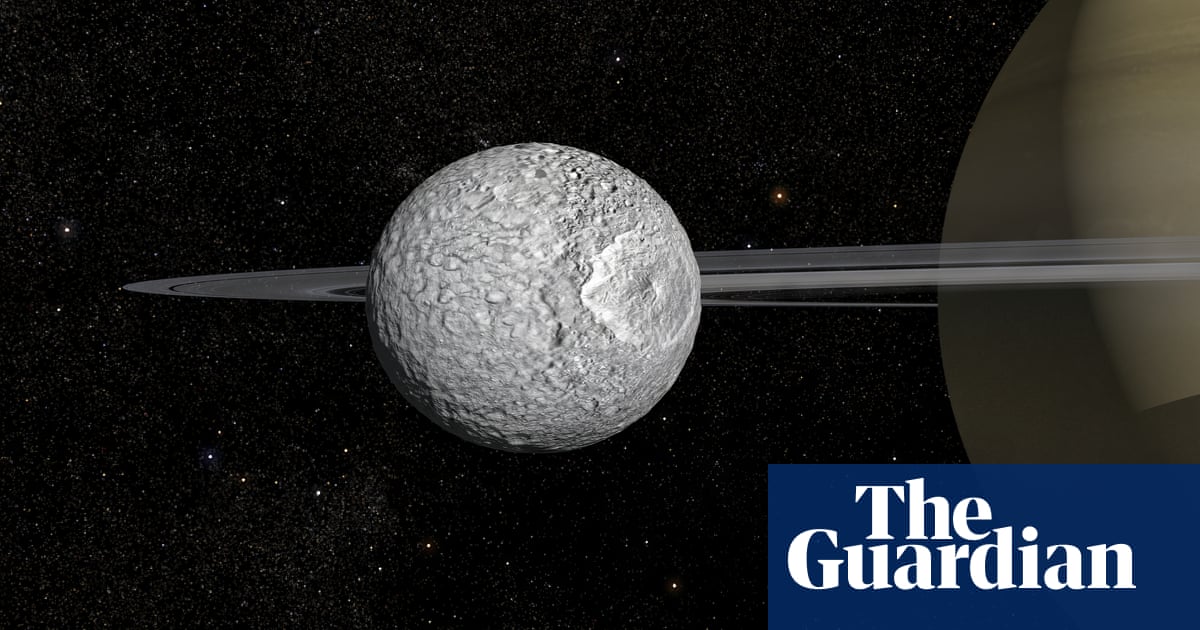

A moon of Saturn that resembles the Death Star from Star Wars because of a massive impact crater on its surface has a hidden ocean buried miles beneath its battered crust, researchers say.

The unexpected discovery means Mimas, an ice ball 250 miles wide, becomes the latest member of an exclusive club, joining Saturn’s Titan and Enceladus and Jupiter’s Europa and Ganymede as moons known to harbour subterranean oceans.

“It’s quite a surprise,” said Valéry Lainey, an astronomer at the Observatoire de Paris in France. “If you look at the surface of Mimas, there’s nothing that betrays a subsurface ocean. It’s the most unlikely candidate by far.”

Peculiarities in Mimas’s orbit had led astronomers to entertain two possibilities: either it contained an elongated core shrouded in ice, or an internal ocean that allowed its outer shell to shift independently of the core.

By analysing thousands of images from Nasa’s Cassini mission to Saturn, Lainey and his colleagues reconstructed the precise spin and orbital motion of Mimas as it looped around the gas giant. Their calculations showed Mimas must possess a hidden subsurface ocean to move the way it does.

“There is no way to explain both the spin of Mimas and the orbit with a rigid interior,” Lainey said. “You definitely need to have global ocean on which the icy shelf can slip.”

Their calculations suggest an ocean 45 miles deep lurks beneath Mimas’s 15-mile-thick icy shell, with temperatures near the sea floor reaching tens of degrees celsius. The ocean would account for more than half of Mimas’s volume. Details are published in Nature.

By astronomical standards, Mimas’s ocean appears to be relatively young, forming in the past 25m years when powerful tidal forces exerted by Saturn deformed Mimas’s core, warming it like a massaged squash ball. The heated core then melted overlying ice, creating an ocean inside the Saturnian moon. The surface remains heavily battered, with one giant impact producing the Herschel crater, named after the astronomer William Herschel who first identified Mimas in 1789.

The discovery of global oceans in moons around Saturn and Jupiter has prompted a flurry of interest from space agencies eager to explore their potential for harbouring life. More than 100 geysers have been spotted on Enceladus where vapour blasts through surface fractures. If life ever evolved on the tiny moon, the plumes could propel extraterrestrial microbes out into space where they could be detected by visiting missions.

Lainey said that since Mimas contained water in contact with warm rock, he would not rule out the existence of life there. But if the hidden ocean is only tens of millions of years old, life may not have had a chance to emerge. “Whether it’s too young, nobody knows,” he said. “I would say: why not?”

David Rothery, a professor of planetary geosciences at the Open University, said that even if Mimas did harbour a subsurface ocean, there were easier places to search for life beyond Earth. “There’s no indication of a connection between the internal ocean, where life could survive, and the surface or space where traces of life could be detected and sampled, such as we have done in the plumes of Enceladus, and hope to do on the surface or in plumes at Europa,” Rothery said. “If there were life inside Mimas, it would be hidden by more than 20km of unbroken ice.

“If the ocean has existed for only 25m years, that may not have been enough time for life to get started and established. Europa and Enceladus are much more promising candidates.”