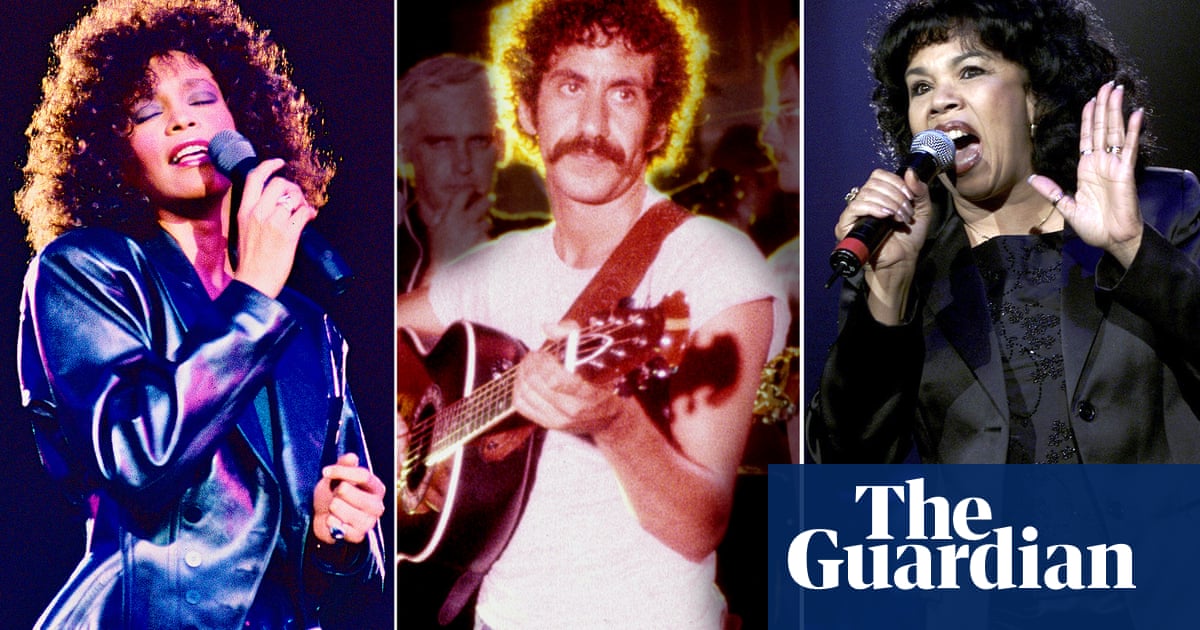

Whitney Houston – It’s Not Right But It’s Okay

I never went to J-school, but I learned everything anyone needs to know about how to be an investigative reporter from Detective Whitney Houston. In just four short minutes, this song describes our hero’s Pulitzer-level investigation into a deadbeat lover: she looks through his phone, digs through the trash, and literally finds the receipts to prove once and for all that he’s a filthy, lying cheater. That’s a bummer, of course, but in the grand tradition of divas such as Gloria Gaynor and Alicia Bridges, Houston reminds us that it’s better to hit the dancefloor than lie in bed wallowing over a pathetic man. “I’d rather be alone than unhappy” is both a celebration of self and god-tier diss. It doesn’t hurt that you can always count on hearing the Thunderpuss club remix of this song during a night out at a gay bar – a little forehead kiss from the cosmos reminding you that even during the most crushing heartbreaks, you will, in fact, end up OK. Alaina Demopoulos

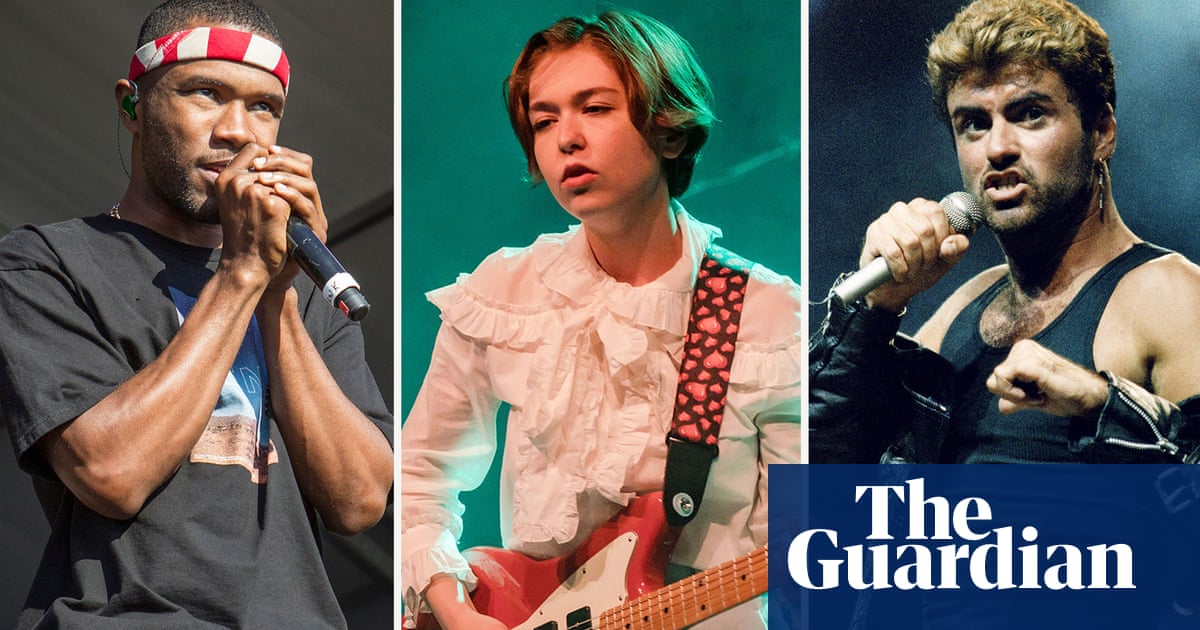

Guns N’ Roses – Estranged

In the early 1990s when they were the biggest band on the planet, Guns N’ Roses released three separate 1-hour documentaries chronicling the making of the videos for Don’t Cry, November Rain and Estranged. On the surface a behind-the-scenes look at the most expensive music videos ever produced, the decades-out-of-print trilogy has survived (barely) as an accidental American epic, inadvertently tracing a band’s arc from young and hopeful to fraught and paranoid. The lavender haze of Axl’s budding love with then girlfriend Stephanie Seymour – who features in the first two vids but is absent from the third amid their messy split – fades to black. Duff’s mounting coke bloat marks the time. The void of Izzy, a no-show for the Don’t Cry shoot who would quit the band weeks later, hangs over everything. That context of excess and melancholy enhances the impact of Estranged, a nine-and-a-half-minute ballad with no chorus that breaks all the structural conventions and represents the band’s ultimate masterpiece before the center could not hold and it all went tits up. Couched between Slash’s mournful guitar solos, Axl’s lyrics (and exceptional vocal work) nakedly account his heartbreak and anguish over the dissolution of his marriage to Erin Everly. It’s a breakup song about the unromantic terminus of grief: of the acceptance and aftermath beyond desperation. As Axl puts it on camera: “November Rain is a song about not wanting to be in a state of having to deal with unrequited love. Estranged is about acknowledging it, and being there, and having to figure out what the fuck to do.” Stars – they’re just like us! Bryan Armen Graham

Fleetwood Mac – Silver Springs

Breakup songs should elicit one of two emotions: rivers-streaming-down-your-face sobs or billowing anger. Perfect breakup songs – like Silver Springs – elicit both. With its slow build up, the song is equal parts melodrama as it is utterly devastating. You can put yourself in it and weep through lines like “I’ll say I loved you years ago / Tell myself you never loved me, now”; working your way up to the throaty roar required to properly sing: “I’ll follow you down ’til the sound of my voice will haunt you / You’ll never get away from the sound of the woman that loves you.” You can also revel in the third-party catharsis it evokes. Like any self-respecting fan of Fleetwood Mac, the saga of Lindsey Buckingham and Stevie Nicks has enthralled me for years. I’ve watched virtually every live performance of this song, always returning to the 1997 reunion show performance, later released as The Dance. There’s not yet a word powerful enough to describe what it is to see past lovers harmonize about the very big feelings that tore them apart. Jenna Amatulli

Sleater-Kinney – One More Hour

There are few things more uncomfortable than watching a couple argue in front of you, especially when neither party is willing to back down. That’s why it took me a while to warm to Sleater-Kinney’s bruised, bristling One More Hour. The 1997 song distils the real-life breakup of vocalists Corin Tucker and Carrie Brownstein into unruly post-punk. It’s drain-circling as duel, and both protagonists show up armed: Tucker, with wounded pleas and a siege of power chords and Brownstein with snide ripostes and a guitar line that nags like a stone in your shoe. There’s a present-tense, if slightly uncomfortable, urgency as the vocalists sing against each other, making it feel all the more real (and, in its resistance of a clean narrative, more than a little queer). There is no clear victor, but One More Hour coalesces beautifully as a nuanced depiction of a breakup’s deep sadness as well as its scorn. Owen Myers

Third Eye Blind – How It’s Going to Be

Were it not for Greta Gerwig’s canny Matchbox Twenty caricature or Weezer’s long tail via TikTok and Olivia Rodrigo, the hangdog stylings of 90s pop-rock would’ve long been relegated to the annals of musical oddities: too dorky, too cheesy, too many men whining. It just so happens that those qualities constitute the ideal breakup ballad – such as this perennially uncool classic from Third Eye Blind’s debut record which bottles the immediate relief of a relationship’s conclusion and the subsequent comedown with searing, self-effacing angst. A riff played on a zither rattles through the track, flickering like a sunburst through slatted blinds. Frontman Stephan Jenkins’ voice is an aberration over the chords: a weary shrug; a bratty kiss-off to a love past its expiry date. But then the cracks form. Quiescent memories awaken. The track ruptures. Jenkins howls into the void: “I wanna taste the salt of your skin!” It’s pathetic, petulant, pleading. In other words: exactly how a breakup feels. Michael Sun

Candi Staton – Too Hurt to Cry

With six marriages under her belt, Staton has more authority than most when it comes to breakups, and she put it to good use. Across her discography there’s every conceivable type of breakup pain, from pre-emptive anxiety (I’m Just a Prisoner) to intense lamentation (Darling You’re All That I Had) to post-breakup regrets (I’ll Drop Everything and Come Running) to actively encouraging others to break up while still trapped in her own doomed relationship (Young Hearts Run Free). But she’s especially good at conjuring the eye of the storm – that feeling in the immediate aftermath where you know you’re going to feel absolutely awful very soon, but right now there’s an eerie kind of clarity. He Called Me Baby is great at this, Staton audibly shaking her head in calm disbelief – but even better is Too Hurt to Cry. Her partner is off to his new missus, and Staton calmly tells him how absolutely devastated she is. The vocal acting is astonishing: starting out contemptuous of this rat, and faux-casual in her observations (“I see your clothes are packed”), the pain starts to seep in. By verse two there’s such finely layered anger and self-loathing in “I neglected myself, baby / devoted my life to you” – and oh, the down-bad way she still reflexively calls him “baby” is so painfully relatable. Then, there’s even a note of amused self-mocking exasperation to the line “I feel so bad, I could just die!” before she nearly loses it as she turns her back on him – “I don’t want to see you leave me” – and then regains her composure with a toxic mantra that lets the anger rush in again: “I’m too hurt, I’m too hurt, I’m just too hurt to cry.” It’s Oscar-worthy stuff, but these three minutes are better than any three-act film. Ben Beaumont-Thomas

Jim Croce – Operator

In music and especially in breakup songs, I tend to prefer righteous anger, bitterness or scorn. But one time at a restaurant, in the middle of some especially pitched yearning for someone, I heard Jim Croce’s Operator (That’s Not The Way It Feels) and have been attached to its sadness ever since. Perhaps it’s because the song, released a year before Croce’s tragic death at 30 in 1973, cuts through time. The narrator, whose ex abandoned him for his “best old ex-friend Ray”, addresses a telephone operator, a bygone concept to anyone under the age of 50. Yet, you know what he’s talking about – confessing your pain to an unwitting stranger, insisting that you’re fine, hoping you could just convince yourself that it wasn’t real. Trying to get better, failing. Trying to be in public, stuck in your own head. Trying to live with the ache of being left behind – a feeling that anyone who’s ever been through it knows, to quote a Taylor Swift song on the subject, all too well. Adrian Horton

Arctic Monkeys – Cornerstone

For all its lush production flourishes and major-key majesty, Cornerstone is about that least glamorous of experiences: a post-breakup bender. In the song’s lyrics, Alex Turner stumbles from one fictitious pub to another, meeting girls and asking desperately if he can refer to them by his ex’s name. Finally, he runs into his ex’s sister, who provides the track’s funny, acidic all-timer of a closer: “You can call me anything you want.” It’s a totally bizarre premise, and that’s why there are few finer breakup songs – Turner perfectly captures breakup feelings that are otherwise rarely immortalised in art: recklessness, self-pity, mild psychosis. It zeroes in on self-absorption to an almost uncomfortable degree; although the track finds Turner in crooner mode, his lyrics are pathetically needy, almost cruel. But you can’t help but root for him – who hasn’t gone out in search for a rebound and found themselves spewing word-vomit about the ex they can’t forget? Shaad D’Souza

Solomon ft Kojey Radical – Phases

Few songs bring up the sorry, slippery mess of emotions caused by a breakup quite as painfully well as Phases, a lesser-known track from last year that soon drilled its way deep into my brain (and Ice Spice’s after she sampled it months later). It’s an instantly relatable heart-tugger about the knots we try to untangle after the final door is slammed shut, grappling with that horribly jarring process of redefinition (“from lovers to haters to nothing”) and how it’s never ever an easy route through with inescapable, and uncomfortable, little triggers (“I still suppress flashbacks of you and I fucking”) making it all that much maddeningly harder. Solomon lasers in on how deeply unnatural the readjustment can feel and with a sad, haunting verse from Kojey Radical (“Sometimes I pick up the phone but put down the pics on the shelf”), shows that it’s something many of us face without ever really knowing if it was the right thing to do. Benjamin Lee