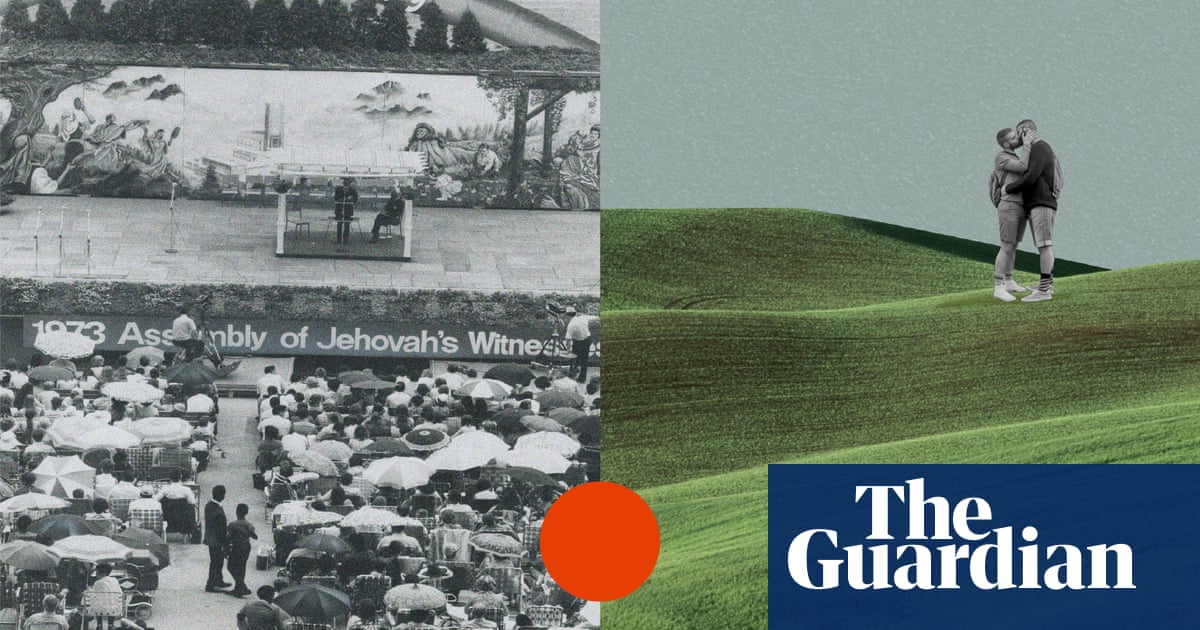

Iused to knock on people’s doors and tell them the end of the world was coming. We were born imperfect, I would say, and soon will come the day of Armageddon when we will all be tested. Be good and you could win life in Paradise. Be bad, and your reward is annihilation. No wonder people would see us coming and turn off the lights.

Stories have always been in my blood. Until a few years ago, I based my life on their outcome. Raised in the UK as a Jehovah’s Witness, I was told we were in “the time of the end”, which meant we were in the third act of Life’s story, when I would soon be rewarded with eternal life on a paradise Earth.

Every Witness child was given a copy of My Book of Bible Stories, a heavy yellow hardback. From the moment I could listen, I was taught the story of Abraham, who almost murdered his son after God commanded him as a test. The accompanying illustration of Isaac tied up on a sacrificial altar as his father looms over him with a knife was terrifying. Then there was Lot’s wife, who was turned to salt for daring to look back at the fire God was raining down on her hometown. I never questioned these stories or their morals. Why would I? They were taught to me at the same time as my ABC. They were my version of “normal”.

My entertainment was heavily vetted. Anything with ghosts or witches was banned. Christmas and birthday colouring pages were ripped out. Looking back, I struggle to think of books that would have been more shocking than the Bible. Babies’ heads dashed against rocks, entire nations murdered by an angry God, an upcoming worldwide genocide of billions … yet it is a tree with coloured lights that was deemed offensive.

I was allowed to choose my own books, but reading was a pastime that came second to religious activities. I attended a mainstream school, leaving after A-levels, but usually Witnesses attain only the most basic education, and are instead encouraged to direct all effort towards preaching. University is frowned upon. Although I was never forced into full-time preaching, there was little encouragement to take my education seriously. Books have always been the easiest way to travel.

George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four gave a label to the “doublethink” and “thoughtcrime” that I accepted as normal. When I read it in my early 20s, I had a genuine watershed moment. The way that “The Party” alters beliefs and insists followers accept these changes without dispute mirrored my community. The story of Winston, who knows the truth and yet must conform for his own survival, opened a door I had never dared to touch.

Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale opened my eyes to the danger of a patriarchy that positions itself as beneficial to women. I had recently become a mother and so the themes of suppression of women and loss of agency in the name of religion inspired a visceral reaction. I was already having doubts about my faith, and this book made them snowball.

Perhaps because my imagination was forged in such bloodthirsty fire, stories have always felt more alive and memorable than nonfiction. What could be a more devastating teacher on the subject of slavery and its subsequent trauma than Toni Morrison’s Beloved? Parts of the story left me so angry that I had to keep putting down the book to compose myself. I read it after I had stepped away from my community, but it only confirmed my doubts. How could a powerful god stand by and watch this happen and not feel compelled to intervene?

A rule I had always struggled to accept was disfellowshipping, when wrongdoers are cut off and even their family are not to have any contact. Shunning those who simply no longer want to be a member is also normal among Jehovah’s Witnesses. Classics such as Thomas Hardy’s Tess of the D’Urbervilles and John Galsworthy’s The Forsyte Saga, which feature characters cast out for allegedly going against the accepted morals of their day, helped me realise the unfairness of such a practice.

In my community, shunning was viewed as a loving action that would bring the shamed one to their senses. This is not love, I realised. It is like what a wicked stepmother in stories would do, locking up a child until they begged to be released. Anything, the child would scream, I’ll do anything if you just let me out of this dark and lonely room.

In my first novel, Another Life, written soon after I stepped away from my community in my 30s and lost many friendships, the character of Anna is cast out of her religion for the sin of no longer believing. In my second, Oh, Sister, I explore the struggles of three women within the confines of a doomsday patriarchal religion based heavily on the Witnesses. Their names – Jen, Zelda and Isobel – form a loose anagram of Jezebel, perhaps the most reviled biblical woman, who was pushed from a window to her death, trampled by horses then eaten by dogs.

In the real-life story of my former community, female characters are not allowed a voice. The elders in charge are men. They make the decisions, and the women (“sisters”) must abide by them. I was often labelled “a sister with opinions” and remained an active member until several years ago, when my doubts became too large to ignore. Despite my ability to speak up, talking about myself and being the centre of attention have never come easily. If you are taught all your life that you are not equal to any man, even the most stubborn must absorb a little of that narrative. Perhaps this is why I wrote these women, so that through their stories, I could process the strangeness of the world that was once my home.

Reviews of Oh, Sister call it “a horror story” and “a dystopian fairytale”, which has been surprising because the world in which these women live was my definition of normal. If not for the power of fiction, perhaps I would still be there now.

Oh, Sister by Jodie Chapman is out now in hardback, and in paperback on 21 March. To support the Guardian and Observer, order your copy at guardianbookshop.com. Delivery charges may apply.