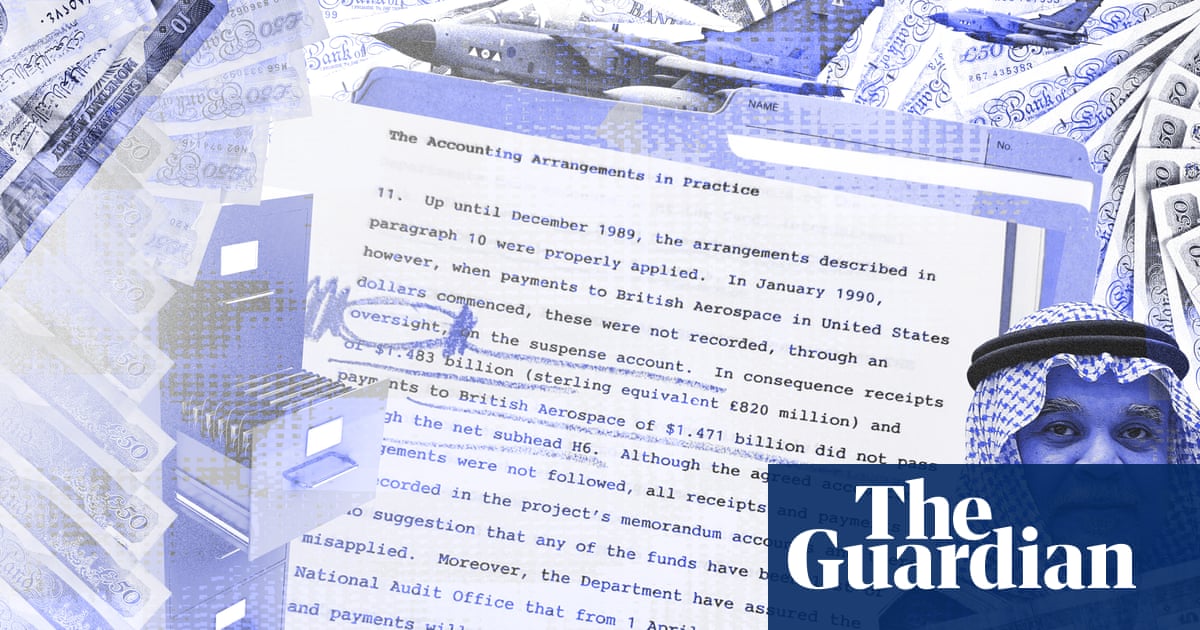

A suppressed official report on alleged corruption in a giant British-Saudi arms contract has been discovered in a public archive, ending a three-decade battle by campaigners for the controversial document to be revealed.

The report, which the Guardian is publishing on its website along with various accompanying documents, is believed to be the only inquiry by Britain’s public spending watchdog, the National Audit Office (NAO), to be so thoroughly censored, with only two MPs allowed to see its conclusions.

Its suppression, along with associated papers in 1992, has been a cause celebre for decades among anti-corruption campaigners, with Labour and Liberal Democrat MPs backing parliamentary motions on three occasions calling for it to be released amid speculation that it contained damning evidence of bribery in the notorious al-Yamamah arms deal.

The cache of papers reveals the report was in effect banned after lobbying by the Ministry of Defence’s top civil servant, who argued publication would enrage the Saudis and threaten thousands of jobs.

The former MoD permanent secretary, Sir Michael Quinlan, also appears to have lied to MPs investigating the deal, by falsely claiming that no commissions were being paid using public funds and failed to disclose his own department’s involvement in regular secret payments to a Saudi prince.

The discovery follows a Guardian investigation into longstanding MoD complicity in corruption and secret payments to high-ranking Saudis to secure defence contracts for Britain over decades. Payments to senior Saudis were allegedly paid as recently as 2017.

Secrets …

The £40bn al-Yamamah deal, initially for the supply of 120 Tornado aircraft, Hawk fighter jets and other military equipment, was agreed in 1985 by the government of Margaret Thatcher and the Saudi defence minister, Prince Bandar bin Sultan.

The UK MoD supervised the deal in a formal agreement with the Saudi government, while Britain’s biggest arms company, BAE Systems, was the main contractor.

Allegations that members of the Saudi royal family were taking bribes on the deal emerged almost immediately. In 1992, the NAO carried out an investigation into the contract.

Such investigations are normally scrutinised in public sessions by MPs on the House of Commons Public Accounts Committee (PAC). However, in this case, the MoD persuaded Robert Sheldon, the chair of the PAC at the time, to hold the session in secret and to then suppress the report.

Quinlan privately argued that thousands of British jobs would be at risk were the public allowed to read the report.

Quinlan said publication would so upset the Saudis that they would cancel future arms deals with Britain. “The whole project operates under a seal of confidentiality. There is a very great sensitivity about the project on the part of the Saudi Arabian government. Open government is alien to them,” he said.

… and lies

Only 10 copies of the report were produced. Sheldon and his deputy were the sole two MPs allowed to read it, or to question Quinlan about its contents in a secret hearing.

In the confidential meeting, they asked Quinlan about the rumours of bribes. Quinlan replied: “Yes, I can give you the assurance that there is no basis to support any suggestion that commission payments have been made using public funds”. Commission payments is often a euphemism for bribes.

Following this meeting, Sheldon told the public he had found “no evidence” of corruption or improper payments by the MoD.

However, Quinlan’s assurance was deeply misleading. It is now known that the MoD not only knew that commissions were paid to a prominent member of the Saudi royal family, Prince Bandar, but that the MoD itself was authorising them on a quarterly basis.

An MoD memo disclosed during a recent criminal trial reveals that in 1988, just four years before the NAO investigation, the MoD’s head of arms sales helped to set up the system of regular payments to Bandar, who had played a key role in negotiating the al-Yamamah arms deal with the British government.

Under the arrangement, Bandar would write every three months to the MoD requesting his allowance. The MoD would then instruct the contractor, BAE, to make the payment from the al-Yamamah funds, which had been paid through the government department.

These payments continued until at least 2007. The Guardian previously revealed that Bandar received more than £1bn through the arrangement.

Although the NAO concluded there was no corruption, it appears to have detected early evidence of funds being diverted. Part of the report observes that the MoD had occasionally paid for “items requested by Saudi Arabia” using the al-Yamamah budget.

“Such items include the purchase of a car and provision of a chauffeur – total cost £88,000 – for Saudi official use,” the report observed.

The cache of documents, including the report, were discovered by the Guardian in Sheldon’s personal archive of papers which he donated to the London School of Economics. He died in 2020.

BAE has previously said all payments were made with UK government “express approval” and were confidential. A spokesperson said: “We are committed to responsible and ethical business conduct and have a zero tolerance policy regarding corruption in all its forms.”

A spokesperson for the MoD declined to comment on whether Quinlan had lied to Sheldon and his committee.

“Payments were disbursed by the MoD on Saudi Arabian government authorisation according to the government-to-government arrangements at the time,” the spokesperson said. “Disbursed funds remained at all times the property of the Saudi Arabian government. It is conjecture to say that the payments were corrupt.”