He’s back. But he never went away. Patricia Highsmith’s diabolically inspired postwar creation Tom Ripley has returned, to luxuriate in our 21st-century age of Instagram lifestyle envy, tacit class paranoia and online identity fraud. He has triumphantly resurfaced in Steven Zaillian’s sumptuous and instantly addictive new eight-episode adaptation of Highsmith’s novel The Talented Mr Ripley for Netflix, starring the incomparable Andrew Scott as the charmer, aesthete and serial killer. It’s a seven-star luxury hotel of a TV show in arthouse black-and-white, which my colleague Lucy Mangan has hailed as quite possibly definitive.

It’s set in the early 60s, but has a queasy resonance for 2024. At an unhurried tempo, Scott’s Ripley is shown surmounting his early unease and likable callow vulnerability, attaining a hypnotic and insidious poise, his irises seeming to merge blackly with his pupils. He even to me seems to sway slightly, like a cobra in the presence of a hamster. Ripley is seen at first in flophouse poverty in New York running petty scams with stolen cheques; he is then approached via a private detective by troubled wealthy plutocrat Herbert Greenleaf (played by Kenneth Lonergan), because Ripley once had a passing acquaintance with this man’s wastrel son Dickie Greenleaf, played by Johnny Flynn. Greenleaf Sr offers Ripley large sums of money to travel to Italy, where Dickie is lounging about with his girlfriend Marge (Dakota Fanning), and persuade Dickie to come home. Instead, Ripley befriends Dickie, deploying his gift for mimicry and flattery, a parasitic conquest that leads to obsession and murder.

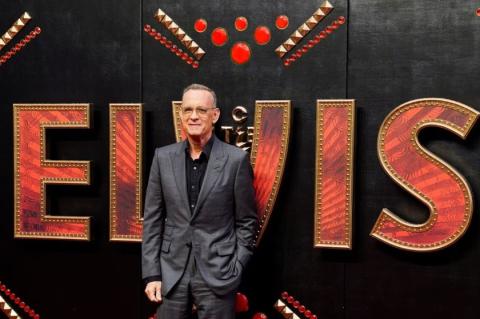

Scott gives a much more downbeat, more realist account of the antihero, or pro-villain Ripley, a contrast to the readably wicked Moriarty that appeared opposite Benedict Cumberbatch’s Sherlock. In Anthony Minghella’s 2000 movie version, Matt Damon played Ripley with a nerdier, needier and more beta-male vibe which at first amuses Jude Law’s Dickie Greenleaf. Scott’s Ripley is closer to Alain Delon’s portrayal in René Clément’s 1960 version Purple Noon, in that Scott’s Ripley cultivates a blankness, an unsettling gift for inscrutable reserve: the sociopath’s resting face. And yet Zaillian’s adaptation gives us much more of Ripley’s essential loneliness and miserable vulnerability. He doesn’t, it seems to me, show us the more worldly and more extravagantly malign figure of Highsmith’s later novel Ripley’s Game, incarnated by Dennis Hopper in Wim Wenders’ 1977 film The American Friend and by John Malkovich in Liliane Cavani’s Ripley’s Game from 2002.

Why is Ripley so fascinating? Partly because there is something so timelessly disturbing about his modus operandi: the perversion of friendship. We might think that to befriend someone, or to be befriended, is a universal good. Aren’t strangers, after all, just friends we haven’t met yet? And yet you can never really know what is happening inside someone else’s head; not even your best friend or lover or spouse, especially someone you met in later life. Who knows what ulterior motives exist in friendship, what gratification of vested interests, or how friendship can for years coexist with rivalry and even dislike? “Frenemy” is word that dates back to Ripley’s birth but has become common currency in recent times.

Ripley’s relationship with Dickie has a long pedigree; it’s the relationship of Mr Hyde with Dr Jekyll, or Dorian Gray with Lord Henry Wotton, or Dirk Bogarde’s creepy valet with James Fox’s indolent man-about-town in Joseph Losey’s movie The Servant. And there is no need of any overtly contemporary interpretation to find that queer dimension: Emerald Fennell’s divisive psycho-thriller satire Saltburn was about an oikish upstart at Oxford conceiving an obsessive love for a beautiful young male aristocrat and being deliriously but secretly overexcited to be invited to this young exquisite’s stately home for the summer.

This kid starts out as Evelyn Waugh’s Charles Ryder but he winds up as Highsmith’s Ripley. This was the allusion that triggered so many of the film’s detractors: the neglected and overlooked class element of Ripley-ism. Ripley speaks to the ruling class distaste for counter-jumpers and presumptuous parvenus. But his existence infuriates those who resent the ironic implication that pleading on behalf of the poor is just the politics of envy. These people aren’t poor, is the perceived sneery insinuation … they’re just pretending, and worse still, they’re like Ripley, part of the vast and spongiform middle class who can code-switch to posh or street when they want. They’re malign and invasive, they want to take the rich people’s cake and eat it.

Paradoxically, Ripley is an adventurer for the new digital age. Each time I revisit Ripley, I’m struck by how we need that original setting because his criminal impostures wouldn’t really work in an era of smartphones and Google searches. And yet he’s a narcissist fit for the new world of social media. Posting and boasting, taking carefully edited and filtered pictures of our wonderful lives and lovely holidays with witty descriptions and humblebrags, compulsively advertising our specialness. I can well imagine a version of Ripley in which he is always on Instagram, stalking Dickie’s feed, posting his own delusional version in New York, using sock-puppet Instagram and X personae to pursue his creepy scam side-hustles – and finally catching up with Dickie in Italy, killing him and taking over his account with new geolocated pictures to create the illusion that he’s still alive.

Felicity Morris’s documentary The Tinder Swindler was about a conman who uses dating sites to siphon money out of his date-victims; it’s about the chilling nexus between sociopathy, greed, emotional manipulation and the opportunities offered by social media for imposture. Tom Ripley is the ancestor of it all. Scott’s seductive performance as the Napoleon of emotional crime delivers all of it and more. If only it wasn’t quite so enjoyable.