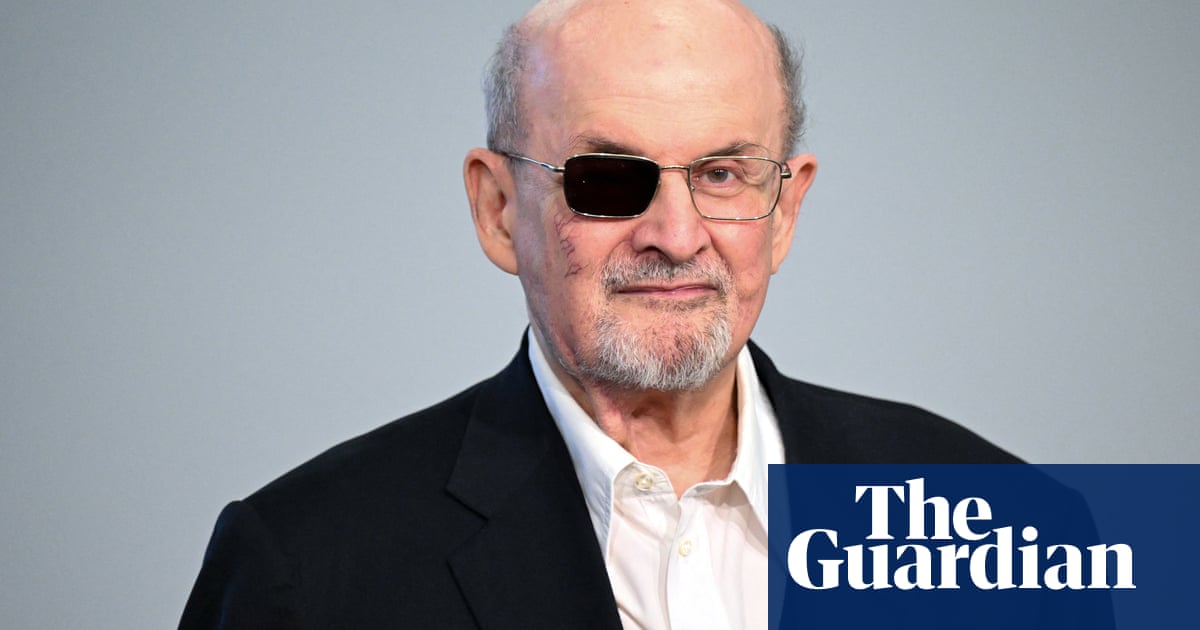

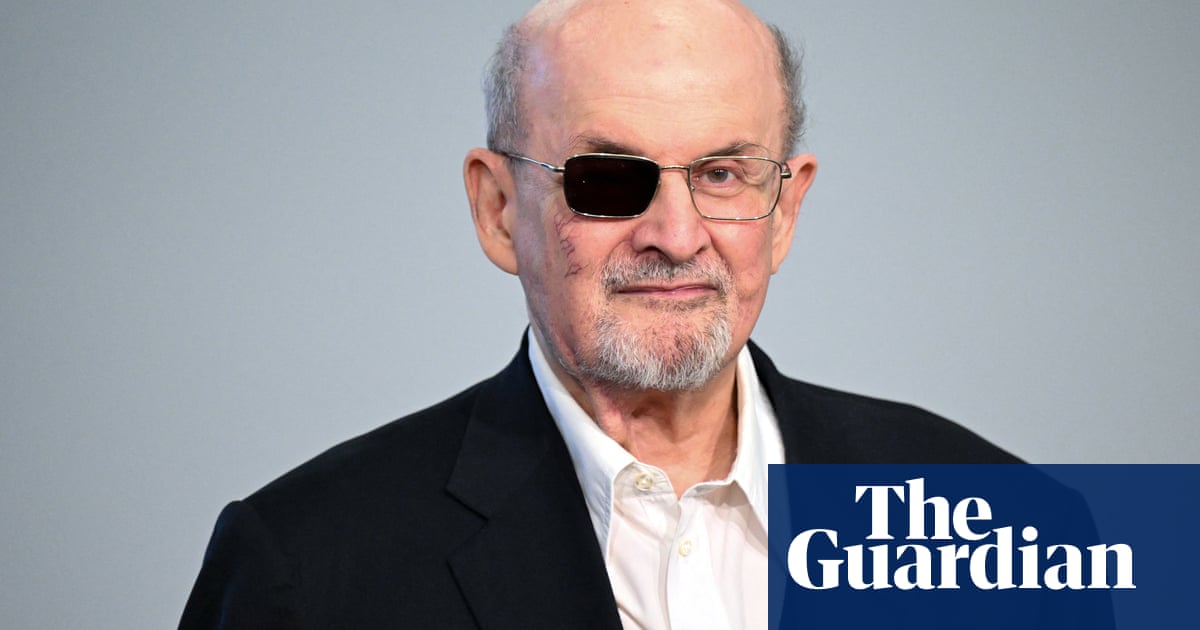

Acouple of nights before he was almost killed by a stranger with a knife, Salman Rushdie dreamed about being attacked by a Roman gladiator with a spear. He’d had similar dreams ever since Ayatollah Khomeini’s fatwa following publication of The Satanic Verses, back in 1989, imagining “my assassin rising up in some public forum or other and coming for me”. When on the morning of 12 August 2022, in Chautauqua in upstate New York, on stage to talk about (of all things) the importance of keeping writers safe from harm, he saw a figure in black rushing towards him, his first thought was “So it’s you. Here you are”, and his second, more bemused, was “Really? It’s been so long. Why now, after all these years?”

In his 2012 memoir Joseph Anton, Rushdie expressed his post-fatwa disorientation by writing of his experiences in the third person, as if the trauma were happening to someone else. Here, as he says, it’s an I-story (and also, since he lost his right one, an eye-story): “When somebody wounds you 15 times that definitely feels very first person.” Joseph Anton (the Christian names of his literary heroes Conrad and Chekhov) was the codename he adopted in hiding to avoid using his own name. Here it’s his attacker’s name he avoids using – he refers to Hadi Matar as “the A”, short for Assailant or would-be Assassin. Or, for Ass: like the Islamist terrorists who have attacked and even murdered people associated with Rushdie, Matar’s knowledge of The Satanic Verses was negligible – he said that he’d read just a couple of pages. After being charged with attempted murder and assault, Matar pled not guilty. Bail was denied, and trial will be held in due course.

When he charged on stage with his knife, some in the auditorium thought it must be a stunt about writer safety, not a real attack. But over the next 27 seconds, before being overpowered by courageous members of the audience (among them the host Henry Reese), he stabbed Rushdie 15 times, in his eye, neck, hand and chest. As he lay on the floor, watching blood pool around him, Rushdie thought he was dying. Among those who saved him (and the book is dedicated to the men and women who did) was a retired firefighter, who pressed a thumb against his neck to stop the flow of blood.

Rushdie doesn’t remember feeling angry with “the A”. But the happiness he’d felt the night before, standing in the summer moonlight, with a new novel finished and proofread, had been destroyed. Worse, he’d been dragged into the past by a man “seeking to carry out a death order from three decades ago” – as if his 16 books since The Satanic Verses counted for nothing; as if that “plain old novel” had reverted to being a theological hot potato. He wonders why he froze when the A lunged at him. He might have run away or fought back. But how does a 75-year-old, in shock, fight a 24-year-old with a knife?

To identify his wounds a crowd of helpers, including two doctors, cut his clothes apart (“Oh. I thought, my nice Ralph Lauren suit”). He was hauled on to a stretcher then airlifted by helicopter to an extreme-trauma ward in the neighbouring state, Pennsylvania. Even before the eight hours of surgery his vision was blurry. And afterwards, on heavy painkillers, he had visions of buildings made of alphabets. When he came round, he was on a ventilator (“like having an armadillo’s tail pushed down your throat”) and parts of his body were stapled together; mercifully, he couldn’t see the “bulging boiled-egg eye” hanging from his face.

Supportive statements came from presidents Biden and Macron, “grudging platitudes” from Boris Johnson, and nothing at all from India. Most heartening were the messages of love from friends: live, live he urged himself. His sister and sons flew over from London. Above all, there was his wife “Eliza”, the poet and novelist Rachel Eliza Griffiths, whom he’d met in a goofy, blood-strewn moment five years before when, dazed by her beauty and following her out on to a balcony, he smashed his face into a sliding glass door (“She literally knocked me out”). They’d been together ever since, married for the previous 11 months and living more privately than he was used to, until this.

The doctors weren’t hopeful. Eliza had been warned he wasn’t going to make it. But by his bedside, she took charge, staying with him 24/7 and recording his recovery on a phone and camera. Within 10 days – his hand in a splint, his damaged liver regenerating, fluid drained from his lung – he was walking with a walking frame. Doctors were amazed. It was a kind of magic realism, a miraculous return from hades.

Transferred to a rehab centre in Manhattan, he hoped for a steady recovery. But there were setbacks: dizziness, low blood pressure, a urinary tract infection, terrible nightmares. The police officers outside his door laughed raucously through the night and there was bandage-changing at 5am. Then came the shock of seeing himself in a mirror for the first time – “this wild-haired one-eyed demi stranger”. He felt bed-enslaved and stir-crazy – until a bound galley of his novel Victory City arrived and lifted his spirits with its closing sentence: “Words are the only victors.”

There were more challenges to come: seven months working with a hand therapist; the unstitching of his right eyelid; a prosthesis fitted in his mouth to make eating less uncomfortable. He doesn’t claim to be brave and gives short shrift to the idea that what doesn’t kill you makes you stronger. Still, it was brave of him to return, a year on, to the amphitheatre where he was attacked, and to feel “lightness. A circle had been closed.” Thanks to love, luck and surgical skill, he’d been given a second chance.

This is “a book I’d much rather not have needed to write,” he says, composed with “one eye and one and a half hands”. But he uses it to “own” what happened, and as a love song to Eliza. As well as documenting his ordeal, it ranges widely, from thoughts about other writers who were victims of knife crime (Samuel Beckett, Naguib Mahfouz: “What was this, a club?”), to memories of childhood and his abusive, alcoholic father, to reflections on violence and on the deaths and illnesses of friends.

There’s also a chapter in which he conducts four imaginary interviews with his attacker, who has described Rushdie as “disingenuous”. Does every disingenuous person deserve to die, Rushdie asks him. The replies are surly: “You don’t know me, you’ll never know me,” the A says. But we learn about his nocturnal gaming, his angry “Incel” loneliness, and a life-changing trip to Lebanon.

“We are other,” runs the epigraph from Beckett, “no longer what we were before the calamity of yesterday.” But Rushdie’s triumph is not to be other: despite his terrible injuries and the threat he still lives under, he remains incorrigibly himself, as passionate as ever about art and free speech as “the essence of our humanity”. At one point he quotes Martin Amis: “When you publish a book, you either get away with it, or you don’t.” He has more than got away with this one. It’s scary but heartwarming, a story of hatred defeated by love. There’s even room for a few jokes. Before the stabbing he was horribly overweight; after hospital and rehab, he finds he has lost 55 pounds, though it’s “not a diet plan to be recommended”.

Knife: Meditations After an Attempted Murder by Salman Rushdie is published by Jonathan Cape. To support the Guardian and Observer order your copy at guardianbookshop.com. Delivery charges may apply.