“They didn’t seem to understand,” writes Liz Truss on page 250 of this unstoppably self-serving reworking of Trollope’s He Knew He Was Right, “that the UK was heading towards an economic cliff and that I was seeking to conduct a handbrake turn to avoid driving off the edge.” The scene is Birmingham, 30 September 2022, just before the self-described Brian Clough of prime ministers gave her keynote address to what turned out to be a divertingly catastrophic Conservative party conference.

The then prime minister is livid about how a cabal of Cinos (pronounced “Chinos” – Conservatives in name only) and other blob-adjacent political invertebrates were trying to nobble the week-old mini-budget she devised with her chancellor of the exchequer Kwasi Kwarteng. By means of this reform, a new globally competitive post-Brexit Britain would emerge. This “unchained Britannia” would be unconstrained by planning regulations, free to frack as never before and able to explore the North Sea for oil despite the ululations of virtue-signalling eco-zealots and the rest of the anti-growth wokerati. This would be a Britain where the super-rich were less hamstrung by corporation or inheritance taxes, and in which the 45p income tax rate (what she calls here the “anti-success tax”) would be little more than a bad memory.

What Truss didn’t seem to understand, now as then, is the handbrake had long ago come off and that both she and Kwarteng, like some latter-day approximations of Thelma and Louise, were barrelling towards oblivion. At Birmingham, in the face of objections from fellow Tories and serious market jitters, Kwarteng U-turned on that tax break for the rich. Later, the pair’s whole plan for growth was junked. Why? Truss is keen to tell us it wasn’t her fault. It was the fault of the economic establishment, apparently, whose members include the Bank of England governor Andrew Bailey, her fellow Conservatives, the IMF and President Biden, not to mention the Office for Budget Responsibility whose “overegged” prognostications of the disastrous impacts hastened speculative panic. They were the reason Britannia had to be chained back up again.

Within days of Birmingham Truss had fired Kwarteng. He learned his fate not from his long-time friend but from Twitter. “We needed a new chancellor who would steady the ship,” she writes coldly. As for Truss, she knew she was doomed a week later when the man she appointed as Kwarteng’s successor, Jeremy Hunt, told the prime minster that her head was “the price the markets wanted”.

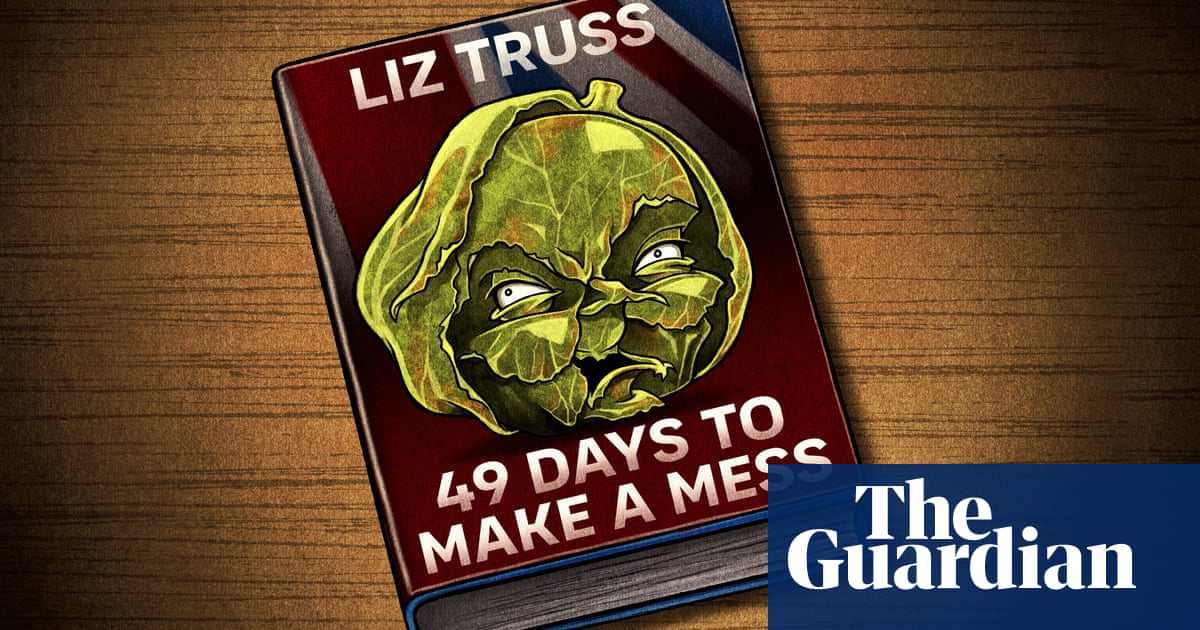

Early in the book, Truss tells us she was known in her first ministerial appointment at the education department as the human hand grenade. Which, with her typical inability to read any given room, she takes as a compliment. After 49 days at No 10, she pulled the pin and blew up her own administration. For that sacrifice, Ms Truss, we salute you.

For all that this is one of the most shamelessly unrepentant, petulant, politically and economically jejune and cliche-ridden books I’ve read, one passage did make me empathise with Truss. It came when, having decided to resign, she gets a phone call from her daughter. Standing in the middle of the school playground, she asks her not to quit. The rest of the book’s tone is typified by the risible hubris of a remark Truss makes at the end of a chapter about her battles with proponents of trans rights as Boris Johnson’s equality minister: “I am not prepared to leave the field until the battle is won.” But this is just folly masquerading as indomitability, a recipe not for victory but for being the last twit standing. In any case, throughout her decade-long career in government Truss has repeatedly done the opposite, scarpering without achieving her stated aims.

It’s a truth insufficiently acknowledged that the political memoir is the basest form of literary genre. Publishers supply fat advances to more or less disgraced politicians despite, one suspects, the gnawing sense that very few people are going to read this guff. As a form it combines score-settling with rewriting history perfectly suited to those with a psychic unwillingness to address their own culpability. In that sense, I suppose, Truss’s memoir is one of the best of its kind. Until, of course, Johnson, who blurbs his successor’s book as “this invigorating tract”, produces his doubtless similarly morally blind true confessions.

“This book is not a traditional political memoir,” she claims. But it is: it’s old school “I was right, you were wrong” in which you’ll find nary a “I’m sorry” or “My bad”. Ten Years to Save the West is at its drollest in its score-settling. Of Nick Clegg she writes: “He would rather be popular than do the right thing. He has now found a much more appropriate home in California and is working for Facebook.” She even has a dig at the Guardian’s Polly Toynbee for criticising her 2012 plans for deregulating nurseries: “As far as the progressive left was concerned, I might as well have proposed arming toddlers with handguns.”

The book’s big reveal is not so much that Truss can’t say sorry, but rather that she didn’t know what was going on at the very heart of the British economy she sought to revivify. The extent of her ignorance is astounding. I kept writing “How did you not know?” in the margins of her chapters on her premiership. How did she, having served in government for so long, not recognise the she would face bureaucratic inertia or that the Bank of England and the OBR would try to scupper her plans? How, most culpably, did she and Kwarteng not have any idea that, as she puts it, “the UK was sitting on a financial tinderbox” at the very moment the pair tried to enact their revolution?

The first and last time she met the Queen, who died two days into Truss’s premiership, Truss was offered good advice, namely: “Pace yourself.” “Maybe I should have listened,” she reflects in a rare moment of self-criticism. Perhaps she should also have listened to her husband, Hugh O’Leary. When she decided to stand for prime minister, he predicted it all would end in tears. He can’t be pleased to have been proved so comprehensively right.

Ten Years to Save the West is published by Biteback (£20). To support the Guardian and Observer, order your copy at guardianbookshop.com. Delivery charges may apply