The semester may be winding down on university campuses around the US, but the anti-Gaza war protests are not. It has been a turbulent month of protests and of administration and police crackdowns on students and faculty members demonstrating in support of the Palestinians and a ceasefire, and against Israel’s war in Gaza.

On the one hand, there have been accusations of antisemitism and, on the other, warnings of attempts to silence free speech and trample the First Amendment have become rife on campuses and on social media. Universities’ reactions to the protests have varied. Some jumped the gun and called the police on their students, while others resorted to dialogue. Politicians have inserted themselves into the battle, taking sides and turning campuses into political arenas.

After weeks of turmoil, one cannot help but assign a failing grade to all the officials handling the issue, from university leaderships and administrators to the White House and Congress.

It all started at Columbia University. Had this issue been handled well from the start at Columbia, things may have turned out differently for everybody, academics say.

Columbia was the first test. The testimony of Columbia’s President Minouche Shafik in front of Congress this month was pregnant with dread and expectation in universities across the country, especially at Columbia.

Columbia’s president took a tough stance against antisemitism but still faced harsh criticism from Republican members of Congress, who said she was not doing enough to protect Jewish students. Some called for her resignation. Shafik focused on fighting antisemitism on campus, but what upset her university’s senate, faculty and students is that she told the committee she would remove professors from their posts. This came after Rep. Elise Stefanik, the New York Republican who was the driving force behind the events that led to the ousting of the presidents at Harvard and the University of Pennsylvania earlier this year, asked about statements made by two professors who are accused of expressing support for Hamas.

The reaction to Shafik’s statements in Congress was immediate on the university campus, with students and faculty criticizing her performance, especially her revealing of information about internal investigations into professors even before they had been informed. The president doubled down, either badly advised or acting out of panic. She ordered the police to remove the demonstrators from their encampment the next day and a number of students were suspended.

Even during the Columbia protests against the Vietnam War in 1968, the university waited a week to call in the police after students occupied five buildings, including the president’s office, and one dean was held in his office for a day. This time, the protesters are mostly peaceful and have kept their encampment in the quad. The accusation of widespread antisemitism on campus was denied by the protesters, a Jewish group and the Jewish students among the demonstration, who celebrated the Passover Seder meal together on Columbia’s campus.

After the police crackdown at Columbia and the arrest of 100 people, all hell broke loose and the snowball of protests grew larger, spreading to universities across the country in solidarity with Columbia’s students. Encampments sprung up on campuses, with students calling for a ceasefire and for their universities to divest from businesses linked to Israel or that supply Israel with arms.

But university administrators called the police to stop the protests. The police’s harsh and violent arrests of students and professors at some universities, the Universities of Texas and Emory in particular, went viral on social media. Hundreds of students were suspended or arrested at dozens of universities, including the University of Southern California, Yale, New York University and the University of Texas. The violent arrest of Emory economics professor Caroline Fohlin sent shock waves through campuses and brought the debate about police brutality back to the forefront.

The White House should not view what is happening on university campuses only through the lens of the campaign.

Dr. Amal Mudallali

The Columbia University Senate criticized Shafik and said her administration had undermined academic freedom and disregarded the privacy and due process rights of students and faculty members by calling in the police. Faculty members told the press that, had the president taken the advice of her senate and handled the issue calmly with meetings and dialogue with all the stakeholders, from the administration to the faculty and the students, maybe things would have been different for Columbia and the other universities.

Politicians did not fare any better. They used the Columbia crisis to further their political agendas. Members of Congress, mostly Republicans and led by House Speaker Mike Johnson, descended on Columbia. Johnson called on Shafik to resign and suggested deploying the National Guard at the university, whose traditions, he claimed, “are being overtaken right now by radical and extreme ideologies.”

The students’ leadership should also have done a better job at preventing extreme external elements from infiltrating their camp, as the universities claim, and stopping those extremists in their ranks from making inflammatory statements, which the schools and Jewish students considered antisemitic and threatening.

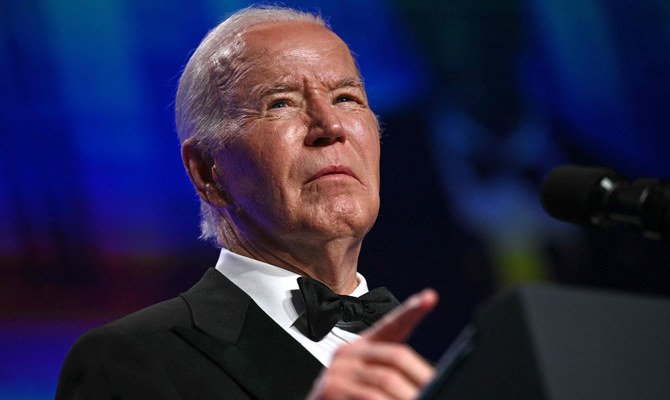

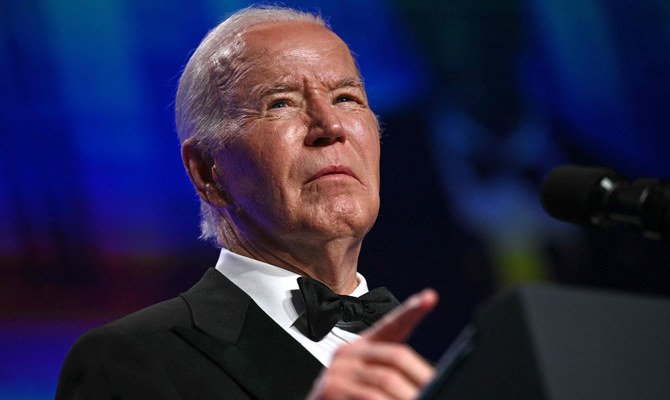

All eyes were on the White House to see how President Joe Biden would handle the issue in an election year and when the young voters’ voice will be critical if he is to win in November. The president condemned the “antisemitic protests,” as well as “those who don’t understand what’s going on with the Palestinians.”

Secretary of State Antony Blinken, while visiting China, considered the protests to be “a hallmark of American democracy.” He said: “Our citizens make known their views, their concerns, their anger, at any given time, and I think that reflects the strength of the country.”

Democrats say these words would have had more impact had the president said them from the White House, instead of a spokeswoman saying that the president “will always support and believes in free speech and nondiscrimination.” But the White House calibrates every word to make sure it does not affect Biden’s election campaign. In its drive not to hurt the president’s chances of reelection, officials are doing exactly what they set out to prevent. Through their caution, they are alienating the very people that Democrats depend on to win elections: liberals, university professors and young voters, including students.

The president could have addressed the nation about this crisis and counseled both sides to calm down, stressing the American principles of freedom of speech and assembly and encouraging dialogue, while at the same time condemning hate speech, intimidation and antisemitism.

Biden will give two commencement speeches next month. The first will be on May 19 at Morehouse College in Georgia, a crucial battleground state, where he will try to appeal to young Black voters. The second will be at the US Military Academy at West Point on May 25. This is a month from now and, by then, it might be too late for the president’s message to reach students.

However, it seems that the president’s campaign is not worried that the university protests will hurt him. Campaign officials reportedly told Politico that these young voters are “a subset of a subset of the electorate, one that’s drawn a disproportionate amount of media coverage compared to its actual political clout.” They cited a Harvard Youth Poll, which showed that just 2 percent of respondents said the “Israel/Palestine” conflict was the issue that concerned them the most.

The White House should not view what is happening on university campuses only through the lens of the campaign. America’s standing in the world as a beacon for freedom, especially the freedoms of speech and assembly, is being tarnished by the images of professors and students being violently arrested and by the prevention of protests in some universities. The sooner the Biden administration addresses this issue, the better for the country and for the president.

• Dr. Amal Mudallali is a consultant on global issues. She is a former Lebanese ambassador to the UN.