The worsening rivalry between the world’s two most powerful countries that has in recent years spread across the world, has now extended beyond the terrestrial, into the realms of the celestial.

As China has become deeply enmeshed in strategic competition with the US – while edging towards outright hostilities with other regional neighbours – Washington’s alarm at the pace of its advancement in space is growing ever-louder.

Beijing has made no secret over its ambitions and a spate of recent successful space missions has shown that the government’s rhetoric is backed by technological advances.

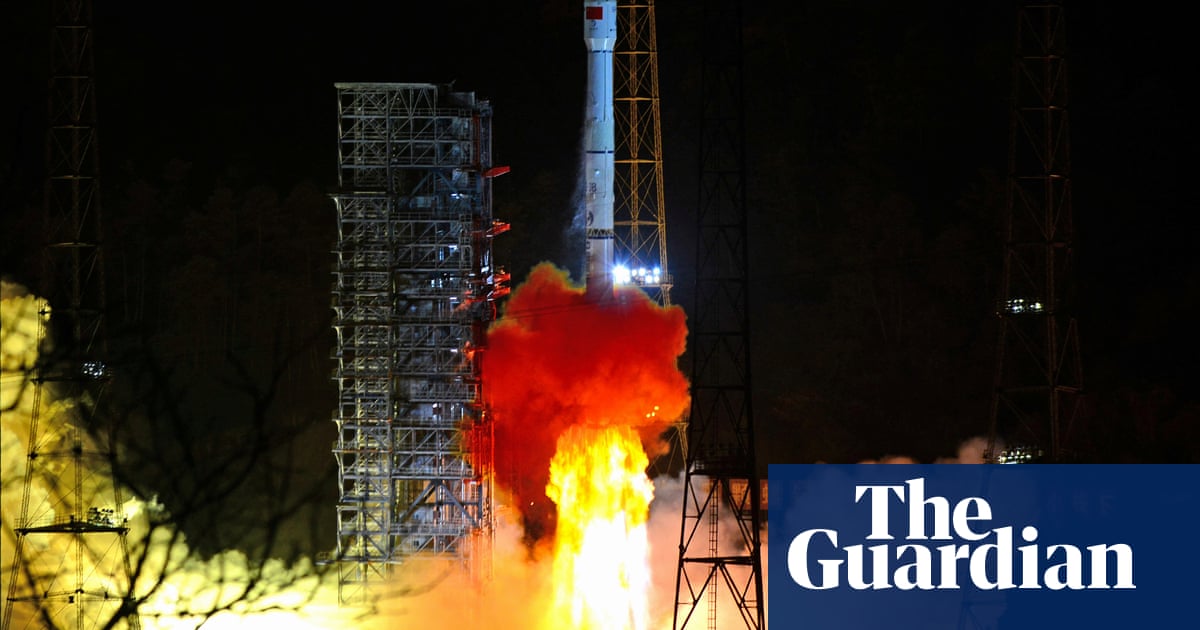

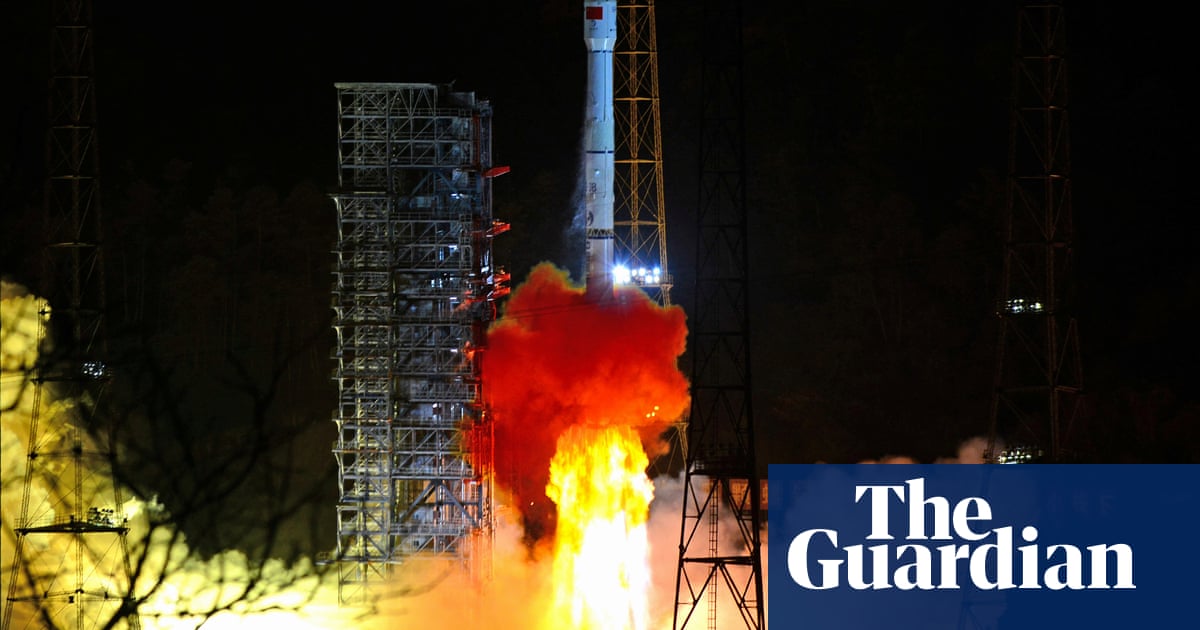

On Friday, China launched a robotic spacecraft on a round trip to the moon’s far side, in a technically demanding mission that will pave the way for an inaugural Chinese crewed landing and a base on the lunar south pole. The Chang’e-6 is aiming to bring back samples from the side of the moon that permanently faces away from Earth.

Earlier this week saw the launch of the Shenzhou-18, Beijing’s latest staffed spacecraft mission to the Tiangong space station, which was developed after China was excluded from the International Space Station.

Along with the three taikonauts, a live fish which has been dubbed “the fourth crew member”, was among the crew. The zebrafish is part of an experiment to test the viability of a large closed ecosystem, involving fish and algae, to help people live in space for long periods.

But the collection of moon samples and the viability of zebrafish are not the only focus for China’s space sector.

The pace of China’s ambitions has drawn concern from the government’s major rival, the US, over Beijing’s geopolitical intentions amid what the head of Nasa has called a new “space race”.

Last week the head of Nasa, Bill Nelson, said the US and China were “in effect, in a race” to return to the moon, and he feared that China wanted to stake territorial claims.

“We believe that a lot of their so-called civilian space program is a military program,” he told US legislators.

There are concerns over China’s development of counter-space weapons, including missiles that can target satellites, and spacecraft that can pull satellites out of orbit.

“On a geopolitical level, China’s space ambitions raise questions about how it might leverage its space capabilities to further its regional and domestic political and military interests,” says Dr Svetla Ben-Itzhak, deputy director of Johns Hopkins University’s West Space Scholars Program.

Gen Stephen Whiting of the US Space Command, told reporters last week that China’s advances were “cause for concern”, noting it had tripled the number of spy satellites in orbit over the last six years.

‘It’s the wild, wild west’

The US and China are indeed in a race, says Prof Kazuto Suzuki, of the Graduate School of Public Policy at the University of Tokyo, but it’s not to simply set feet on the moon like during the cold war. Rather, it’s to find and control resources, like water.

“It’s a race for who has better technical capabilities. China is quickly catching up. The pace of Chinese technological development is the threatening element [to the US],” he says.

Suzuki says international agreements don’t allow for national appropriation of resources on the moon, but in reality “it’s the wild, wild west”.

“Generally speaking China wants to be first so they have the right to dominate and monopolise the resources. If you have the resources in your hand then you have a huge advantage in the future of space exploration.”

The US and China are leading the development of separate space station programs for the moon. The US-led Artemis program includes plans for a “Lunar Gateway”, a station orbiting the moon as a communication and accommodation hub for astronauts, and a scientific laboratory.

The Americans however, “are not so interested in owning the moon because they’ve been there”, Suzuki says.

“They know it’s not really a habitable place, they are more interested in Mars. So for them the Lunar Gateway is sort of a gas station for the journey to Mars.” If the Artemis program can source water from the moon, it could be processed to create rocket fuel from the hydrogen and oxygen.

In contrast, China and Russia announced in 2021 joint plans to build a shared research station on the surface of the moon. The International Lunar Research Station (ILRS) would be open to any interested international parties they said. However the US would unlikely be among them given its poor relations with both China and Russia.

Suzuki says the China-Russia station “is supposed to serve like the research station in Antarctica”, which is within the rules of international space treaties. “But if it turns out to be a station to base their territorial claims, then that is against the rules.”

The US is gathering allies to ensure China doesn’t win the space race. Earlier this month, not long after China announced its intentions to land a person on the moon, US leader Joe Biden and his Japanese counterpart Fumio Kishida pledged to send a astronaut from Japan – China’s historical rival – to the moon on Nasa’s Artemis missions in 2028 and again in 2032.

But China is also gathering allies. It has partnerships or financial stakes in projects across the Middle East and Latin America, and around a dozen international members for its ILRS.

But Ben-Itzhak notes there are some overlapping memberships. Also “neither bloc has instituted exclusionary practices thus far, which is promising”.

Ben-Itzhak says the US and China are indeed engaged in a race, but the term doesn’t fully capture “the complex, nuanced dynamics currently unfolding in space, in terms of the diverse and increasing number of actors and initiatives, and no clear end goal in sight”.

“The real challenge in space is not just about reaching a specific milestone, like planting flags or collecting rocks; it is about establishing a sustainable, resilient presence in an incredibly challenging environment. This is a test against our own abilities.”