In 2017, the New-York-based freelance photographer and film-maker Will Strathman received a thrilling email: the megaproducer Amy Pascal wanted to talk. Her initial message explained that he had been recommended by someone at a fashion brand for whom Strathman has previously worked. On the phone, Pascal described a TV show she planned to pitch to Netflix that would showcase rare beauty spots around the world. Would he be interested in going to Indonesia to create a storyboard for the pilot?

It was a surprising opportunity to get out of the blue. But Strathman was a talented professional and felt he could deliver what Pascal needed. He paid for a flight to Jakarta and worked tirelessly photographing locations, before spending hours each night updating Pascal on the phone. He was exhausted and strapped for cash, but Pascal assured him that he would be reimbursed for all his expenses and rewarded with a healthy day rate.

Strathman borrowed money from his parents and returned to Indonesia twice more that year, racking up bills of $54,000 (about £40,000). Then, one night in Jakarta, he received a panicked phone call. It was from his father, who told him the truth: Strathman had never spoken to Pascal.

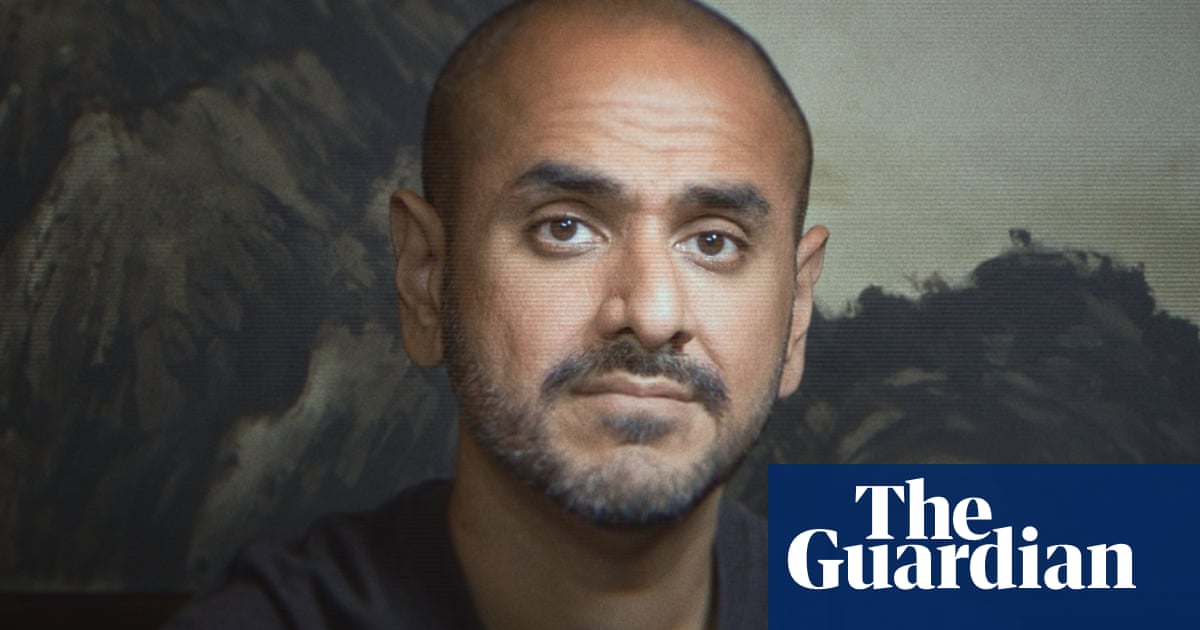

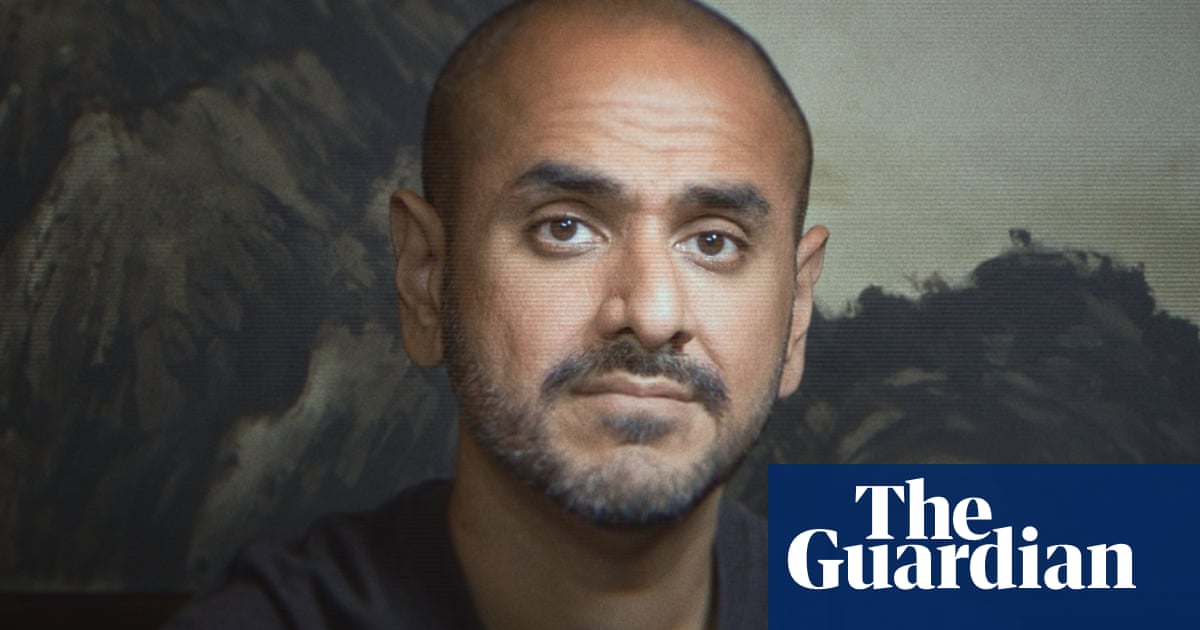

Hollywood Con Queen is a three-part series from Apple TV+ that tells the story of Hargobind “Harvey” Tahilramani, who it is alleged spent years impersonating some of Hollywood’s most powerful women, including Kathleen Kennedy, the president of Lucasfilm, Annapurna Pictures’ founder Megan Ellison and the investor and producer Wendi Deng Murdoch. He then apparently lured budding film-makers and actors to Indonesia for film projects that didn’t exist, leaving his targets devastated and thousands of pounds out of pocket.

The documentary is based on the work of the journalist Scott Johnson, who, with the help of the private investigator Nicole Kotsianas, broke the story in 2018 and wrote the 2023 book The Con Queen of Hollywood: The Hunt for an Evil Genius.

Buying expensive flights to Indonesia on account of some emails may sound outlandish, but it was a con many people in the film industry might fall for. “We had to convey how people’s involvement wasn’t so unbelievable if you understood freelancers in the film business,” says Chris Smith, the series’ director and the man behind Tiger King, Fyre and Bad Vegan. “I worked independently almost my entire life and you would get calls out of the blue giving you an opportunity. When I was 25, I had a message on my answering machine from Michael Moore asking me to shoot his new film. I was a nobody from the Midwest and he was a hero of mine. That was no different from the call these people were getting.”

According to the show, Tahilramani didn’t only offer bogus work opportunities. Things often took an unsavoury turn, with victims being led into phone sex, or being asked to perform explicit scenes down the line. “You could say that people should be more sceptical, but the way he would get people to engage was very sophisticated,” says Smith. “He would research people that his target had worked with on a job, then pretend to be an executive at that company – so, somebody who wasn’t the person they were dealing with, but would be aware of who they were and could feasibly have been recommended to them. You couldn’t necessarily factcheck the connection, but it was plausible.”

Johnson appears throughout the series, looking increasingly burdened. “The search for the Con Queen was tiring,” he says. “I kept getting all kinds of conflicting reports. It wasn’t really clear who he was.”

Things didn’t get easier once he had tracked down Tahilramani. “He has this endless energy and appetite to delve into everything and anything. That in itself became exhausting for me, for my family, for my kids,” says Johnson. “He called morning, noon and night. It wasn’t just the frequency of the calls, but also this endless barrage of sleight of hand and misdirection. The effort of trying to understand what is true and what isn’t when you are bombarded by half-truths and lies is a lot.”

Of course, some con-artist tales in fiction and nonfiction, from Netflix’s Ripley to the self-proclaimed social media “scammer” Caroline Calloway, leave the audience admiring their ingenuity and even rooting for them. “We were fascinated by how meticulous his research was and the ability of somebody to achieve that time and time again with hundreds of victims,” says Smith. “On the surface level, it’s impressive.”

But the series never warms to Tahilramani’s schemes. Many of the victims who appear on screen look traumatised. “When you see the devastation it caused for the victims, that quickly undermines any ability to root for the accomplishments of the con artist,” says Smith.

Hollywood Con Queen is careful not to afford Tahilramani, who is fighting extradition from the UK to the US, the empathy he denied his targets. Johnson frequently labels him a “psychopath”, which he says “came up in court testimony during his extradition hearing, from expert witnesses and medical experts who had evaluated him in prison and delivered their judgments about his mental state and pathologies”.

Tahilramani never stopped trying to manipulate Johnson and frequently tried to get him to sympathise with him by recounting his difficult childhood and life. Yet Johnson remained unmoved, citing Tahilramani’s “remorseless drive to punish others while expecting something very different in return”.

Still, Johnson and Smith admit that, for all his misdeeds, Tahilramani put the “art” into “con artist”. As Smith puts it: “There are just so many ingredients in this performance that were deeply malevolent and psychopathic and it’s something to behold: the sophistication, nuance, subtlety and boldness of it. It’s disturbing, but you can’t deny there was a certain artistry to it.”