Who scares wins. That has been the motto of many, often successful Conservative election campaigns. Fear may not be an edifying strategy for securing power, but the Tories have repeatedly demonstrated that it can be highly effective. Time and again, they have persuaded voters that Labour is just too risky to be trusted with government. The “red scare” of 1924, whipped up with the aid of the fraudulent Zinoviev letter, brought an abrupt end to the short life of the first Labour government. The “tax bombshells” dropped on Neil Kinnock in 1992 exploded his dreams of becoming prime minister. Tory claims that Ed Miliband would wobble atop a “coalition of chaos” helped to floor that Labour hopeful in 2015. The big scare has often been a winning formula for the Tories.

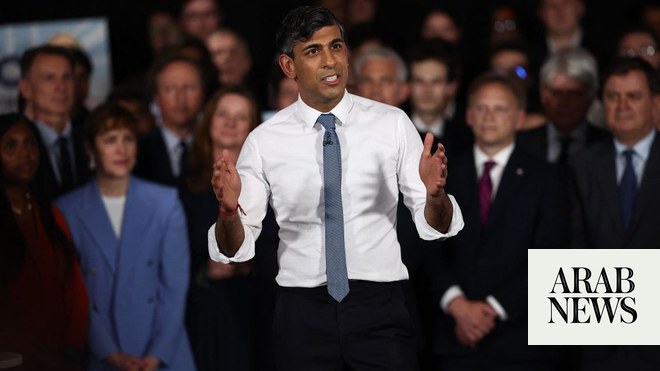

So it was pretty much inevitable that Rishi Sunak would press a quivering finger on the fear button. Not least because he is so short of any other ideas for making the general election look competitive for his party. He’s previously tried marketing himself as Mr Stability, Mr Delivery and Mr Change. None of these iterations has put a dent in Labour’s headline poll ratings. They insistently place Sir Keir Starmer’s party about 20 points ahead of the Tories. In his most recent attempt at a relaunch, an exercise he performs almost as often as he changes his undies, the Tory leader tried another costume. This time he cloaked himself in the garb of Mr Security. In what Downing Street puffed as a big speech, the prime minister tried to chill the country’s bones with the warning that Britain is entering a very dangerous period. His ostensible subject was the threat from “an axis of authoritarian states”. His electoral purpose was to try to build an argument that voters will be safer sticking with him than taking a punt on Labour.

There are at least three big obstacles for the Tories in making this approach work in the current climate. The first is that successful exploitation of the security card depends on the person playing the card being perceived as a strong personality. Voters are much more likely to see Mr Sunak as a weak and floundering character. When pollsters invite the public to compare him head-to-head with Sir Keir, the Labour leader comes out on top as the preferred candidate to be prime minister.

The next serious handicap for the Tory leader is his government’s poor credentials on security issues. It is hard to promote yourself as the only leader who can keep Britain safe when you are gifting early release to criminals because prisons are rammed to bursting while presiding over hollowed out armed forces and failing to keep your promises to control the country’s borders. Likewise, trying to paint Labour as a tax-raising menace, as Jeremy Hunt attempted to do on Friday, is a stretch when it is your party that has hiked taxes to a 70-year high. Making security a defining election issue also invites voters to consider how much responsibility for chaos and crises lies with the past 14 years of Conservative government. Brexit – who did that? Liz Truss – who owns her? Boris Johnson – who was it who inflicted that rogue prime minister on the country?

Yet another pitfall of the fear factor is that it tends to be effective only when it goes with the grain of pre-existing worries among the voters. Scare tactics need to have at least some shred of credibility. Trying to alarm the electorate about Labour didn’t work for Winston Churchill in 1945 when he alleged that Clement Attlee could only implement socialism by relying on “some kind of Gestapo”. Contemplating the solid, patriotic figure of Attlee, and knowing of his important role in the wartime coalition, voters just couldn’t visualise him in a Nazi uniform. Churchill’s unworthy attack made its author look ridiculous. Fear didn’t work for the Tories in 1997 when their “New Labour, New Danger” campaign attempted to portray Tony Blair as a devilish trickster with “Demon Eyes”. Voters had made up their minds that his reforms to his party were authentic. That Tory assault just made the assailants look cartoonishly desperate.

Rishi Sunak has previously tried marketing himself as Mr Stability, Mr Delivery and Mr Change. None of these iterations haves put a dent in Labour’s headline poll ratings

For all the effort they will put into it, the Tories are going to struggle to turn Sir Keir into a convincingly frightening bogey figure. When gathered into focus groups by pollsters, voters often have rude things to say about the Labour leader. Scary is rarely one of them. Central to his project has been de-risking perceptions of Labour. There’s a reason the Labour leader bangs away so much about his being “a changed party”. The de-risking has principally been done by spending a great deal of time trying to convince Britons that Labour can be trusted with national security, the economy and the public finances, often areas of vulnerability for the party in the past. The evidence to hand suggests he has succeeded. Unless the polls are utterly misleading, voters find the prospect of extending Conservative rule for a further half decade a much more blood-shivering thought than they do the prospect of Labour coming to power.

The determination not to offer any hostages to fortune was a strong feature of Labour’s event on Thursday when Sir Keir effectively fired the starting gun for his election campaign, even though not a vote may be cast for six months or more.

Some who made the trip to Essex to witness the slickly choreographed launch groaned that neither his speech nor the accompanying pledge card contained anything excitingly new. That is to miss the point. The purpose is to arm Labour’s candidates and activists with bite-sized, easily memorised versions of the key offers designed to indicate the direction of travel of a Labour government and link its answers to the country’s immediate challenges with its longer-term “missions” to make Britain better. The party will be tracking the degree of cut-through achieved by the card. Given how many things compete for the attention of the public, Labour’s campaign strategists will think themselves to have done well if the average person goes into the polling booth knowing three of the six “first steps” that Labour says it will take in government.

Suspicious minds have noted the absence from the card of several of the party’s larger ambitions. There’s nothing about housebuilding. Nor the “new deal for workers”. Nor the plan to take rail operators back into state ownership. Labour insiders insist that those commitments will be in the manifesto. They’re missing from the cards because it is reckoned, which is revealing in itself, that the promises to tackle people traffickers, crack down on antisocial behaviour and assist public services need to be upfront and central because they will be most critical to a successful campaign. The audacious “mission” to turn the UK into the fastest-growing economy in the G7 was left off the cards because, according to a senior member of Sir Keir’s team, “it doesn’t mean much on the doorstep”. The plan to set up a new state-owned clean energy company did make the cut “because it is incredibly popular”.

A big offer about childcare, which many expected when the pledge card was first discussed, isn’t present because it couldn’t be reconciled with Rachel Reeves’ promise-limiting fiscal disciplines. It is demonstrative of Labour’s risk-aversion that “tough spending rules” gets such a prominent place on the card and the consequences of this are felt in everything else the party feels able to say. The promised early initiative to tackle the backlog of people waiting for NHS treatment is not a large one in the context of the epic size of waiting lists. The plan to tackle teacher shortages is even more modest. The insistence that Labour will not pledge anything it can’t be sure of being able to deliver has been relentless.

This flows from a reading of the electorate that interprets the public as too cynical and mistrustful of politicians to buy into grandiose claims. The Labour leader talks in a way which suggests he thinks that what voters most crave at the moment is reassurance and predictability. At the launch, Sir Keir issued a new slogan for his party, one faithfully echoed by the shadow cabinet. “Stability is change” is Labour’s latest, faintly Orwellian, mantra.

The contrast between the Tory and Labour leaders tells us how each hope to frame the choice at the election. Scary Sunak sounds like a man trying to keep everyone awake at night. Soothing Starmer sounds like a man who wants you to be able to sleep a bit more soundly. Most people like their shut-eye.

Andrew Rawnsley is the Chief Political Commentator of the Observer