Think of a man viewing images or footage of child sexual abuse online, and what comes to mind? I’d bet that for most of us this horrible thought experiment conjures up a Jimmy Savile-style monster sitting in front of the computer screen. But new research from the Lucy Faithfull Foundation, a child sexual abuse prevention charity, highlights how this paradigm does not by itself account for the scale of online offending. Cling to it too hard and it could hamper our ability to prevent the abuse of children.

Because child sexual abuse is such a horrific and unthinkable crime, we tend to “other” the men who do it. They won’t be men in our families, workplaces and communities, but evil individuals in other people’s lives. This is comforting for us adults, but the complacency it engenders puts children at risk. It turns child sexual abuse into something that happens to other people’s children, not those you love, and if it were happening, of course you’d know because you would be able to spot it.

The figures tell something different: child sexual abuse is depressingly common, with at least 15% of girls and 5% of boys experiencing it before the age of 16, and abuse within the family is one of the more common types reported to police. The sad truth is that many of us will unwittingly know men who have sexually abused children.

Another misperception is that child sexual abuse is driven primarily by the perverted sexual attraction some men feel towards pre-pubescent children. That accounts for some offending, but it is far from the whole story: child sexual abuse, like other sex crimes, can be more about risk, power and control; and it is also very much a crime of opportunity. If there is more opportunity to offend, more child sexual abuse will happen.

There is perhaps no place that offers greater opportunities to engage with child sexual abuse than the internet, whether through viewing images of child sexual abuse, or creating them by grooming and exploiting children online. This type of offending is growing: in 2022, the police arrested 850 people a month for online sexual offending. These figures are the tip of the iceberg. The National Crime Agency estimates that up to 850,000 people pose a sexual threat to children online and offline.

The Lucy Faithfull Foundation (which receives charitable funding from the Indigo Trust, of which I am a trustee) runs various interventions, including a helpline, for men who have offended or who are at risk of offending, as part of its work to prevent child sexual abuse. It published a paper last week, based on its clinical work, that highlights that most people accessing the helpline reported problematic use of legal pornography

Viewing pornography does not mean someone will necessarily escalate to illegal sexual images but, for the men the foundation worked with, “adult pornography often serves as a gateway to viewing sexual images of children”.

The theory about how one leads to the other is thought to be because some people become desensitised in their response to pornographic stimulus. Porn has never been more easily available: it is the subject of one in four internet searches, and the four largest pornography sites received a combined 11bn visits a month in 2020.

Porn platforms make more profit the more they keep individuals engaged. Exploitation and abuse of women is rife in the industry – both in the production side and also in the way it depicts sex. There is a vast amount of violent and coercive content that features women reacting positively or neutrally towards aggression.

Some people report needing to consume increasingly novel – and in some cases, extreme – forms of pornography in order to get the same “hit” as from when they first started watching porn. The online world makes that entirely possible. So some men who have ended up viewing sexual images of children may not have originally been sexually attracted to children, according to the Lucy Faithfull Foundation.

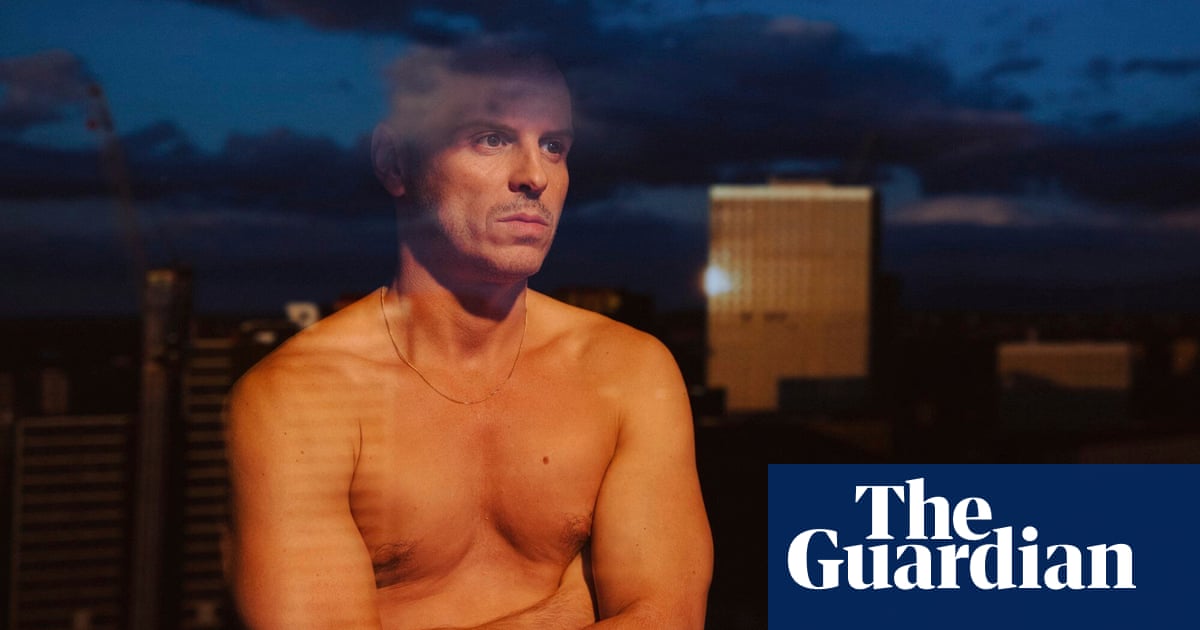

Another charity, the Centre of Expertise on Child Sexual Abuse, highlights that the most striking feature of men who view but do not produce sexual images of children is their “ordinariness” compared with those convicted of contact child sexual abuse.

This makes for uncomfortable reading because it challenges our preconceptions about the men who view child sexual abuse online.

But it is so important in understanding how to prevent online abuse. There is more to be done by relentlessly targeting and taking down illegal online content, but also intervening and disrupting men at risk of veering towards viewing child sexual abuse imagery could help stop the appalling abuse of children involved in production and sharing of this content. The Lucy Faithfull Foundation piloted a chatbot on PornHub that popped up if someone tried to search for unlawful content involving children. It directed them to support services to stop their behaviour and during the 18 months it was in operation the number of searches fell.

Rightly, there has been a broader debate about the impacts of porn in light of evidence suggesting that exposure to violent pornography is associated with attitudes supporting violence towards women in men, and that early exposure to pornography is linked to harmful sexual behaviours in children and young people, including sexual abuse perpetrated by young people towards their peers.

There is still a huge amount we don’t know but, as with other potentially harmful behaviour, it is likely to be riskier for some individuals than others.

The emerging evidence that, for some men, an unhealthy relationship with pornography may be the first step to engaging with online imagery of child sexual abuse is a reminder that the conversation about porn cannot stop at how to safeguard children and young people, as critical as that is. We also need a better understanding of the long-term harm pornography can have on adults, and how they might be able to protect themselves.

Sonia Sodha is an Observer columnist