Willie Mays was the epitome of what came to be known as a ‘five-tool player’

He was exceptional at hitting for average, hitting for power, fielding, throwing and baserunning

For the latest updates, follow us @ArabNewsSport

Mays was the epitome of what came to be known as a “five-tool player” — meaning he was exceptional at hitting for average, hitting for power, fielding, throwing and baserunning

His snag of a fly ball in the 1954 World Series, sprinting with his back toward home plate some 460 feet away, is known simply as The Catch

Mays was ranked second on The Sporting News’ 1998 list of the 100 Greatest Baseball Players — behind Babe Ruth and ahead of Ty Cobb

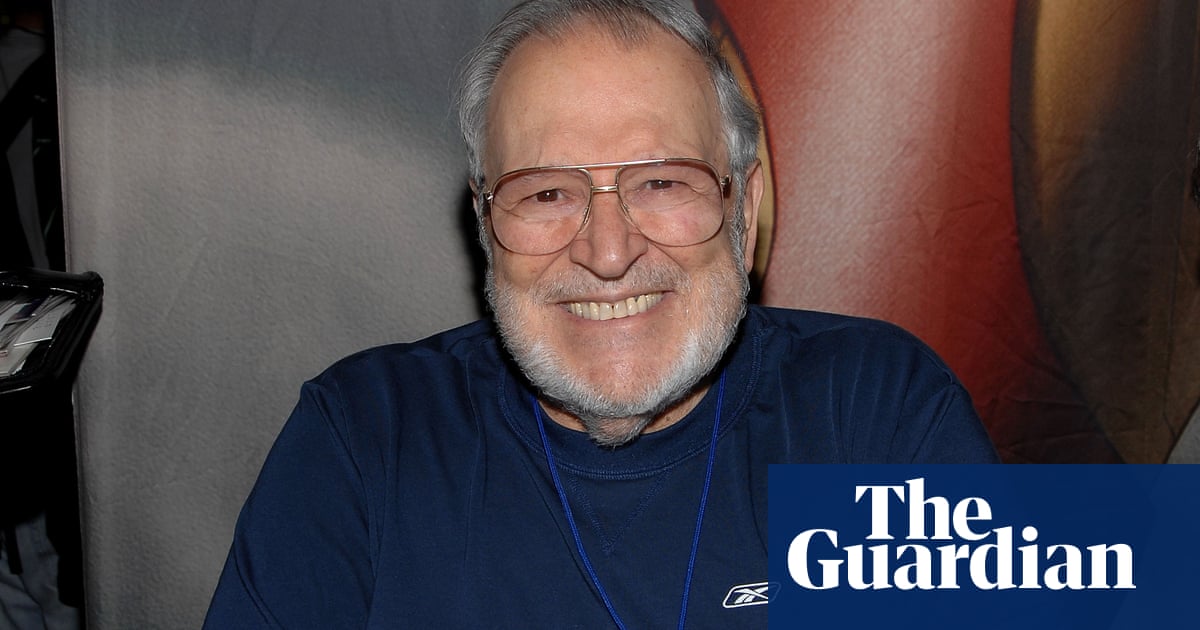

REUTERS: Willie Mays, the Hall of Fame centerfielder whose all-around skills made him one of greatest baseball players of all time, died on Tuesday at the age of 93, Major League Baseball announced.

Mays, who brought an explosive exuberance to the game in his peak years, died of heart failure, the San Francisco Chronicle reported.

Mays played 23 seasons for the New York Giants, San Francisco Giants and New York Mets, from 1951 through 1973.

In his prime, he could do it all on the baseball field. Mays was the epitome of what came to be known as a “five-tool player” — meaning he was exceptional at hitting for average, hitting for power, fielding, throwing and baserunning.

But Mays’ talent was only part of what made him a superstar. He also played with a verve and passion that were discernible even to spectators in the cheap seats. He was known for playing stickball with kids on the streets of Harlem, near the former Polo Grounds where he played.

In the real games, fans delighted when Mays would sprint with such speed and fury that he would run out from under his hat as he stole a base or chased down a flyball to deep centerfield.

His snag of a fly ball in the 1954 World Series, sprinting with his back toward home plate some 460 feet away, is known simply as The Catch.

“He could do everything and do it better than anyone else, (and) with a joyous grace,” wrote New York Times sports columnist Arthur Daley.

Mays, known as “The Say Hey Kid” because of his standard greeting, was ranked second on The Sporting News’ 1998 list of the 100 Greatest Baseball Players — behind Babe Ruth and ahead of Ty Cobb.

Baseball-Reference.com ranks him fifth all time using the modern statistic Wins Above Replacement, which measures a player’s overall value, behind Ruth, pitchers Walter Johnson and Cy Young, and his godson Barry Bonds.

Mays was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1979, his first year of eligibility, won the Most Valuable Player award twice and was named to the all-star team 24 times, a record shared only with Hank Aaron and Stan Musial.

When he retired, Mays held third place on the all-time home run list with 660, behind Aaron at 755 and Ruth with 714. He was also the first ballplayer to hit 300 homers and steal 300 bases.

Willie Howard Mays Jr. was born in the gritty steel town of Westfield, Alabama, on May 6, 1931, during the segregation era and was inspired early to play ball by his father and an uncle, he said.

“My uncle would say every day, ‘You’re going to be a baseball player. You’re going to be a baseball player, and we’re gonna see to that,’” he said. “At 10, I was playing against 18-year-old guys. At 15, I was playing professional ball with the Birmingham Black Barons, so I really came very quickly in all sports.”

Mays joined the New York Giants of the National League early in the 1951 season, four years after Jackie Robinson had integrated Major League Baseball. He failed to get a hit in his first 12 trips to the plate before smacking his first, a home run off future Hall of Fame pitcher Warren Spahn.

Mays went on to win Rookie of the Year honors in 1951 with a .274 average, helping the Giants come from 13 games behind the Brooklyn Dodgers before his team won the pennant on a legendary home run by Bobby Thomson. Mays, then 20 years old, was on deck when Thomson hit his home run, later telling reporters he was so nervous he prayed he would not come to bat.

Mays missed most of the 1952 season and all of 1953 while serving in the US Army during the Korean War, spending much of his service time playing for the Army baseball team.

He returned to the Giants in 1954 and won the first of his two Most Valuable Player awards as he paced the Giants to a four-game World Series sweep of the Cleveland Indians. In the first game of that series, Mays pulled off The Catch, which remains one of the most memorable plays in baseball history.

At New York’s Polo Grounds, the Indians’ Vic Wertz hit a shot to deep centerfield. Mays turned, sprinted toward the wall, made a graceful over-the-shoulder catch and then immediately whirled around and made a perfect throw that kept two Cleveland baserunners from advancing.

“I was a guy, when I first came up, I believed I could catch any ball that stayed in the ballpark,” Mays told an interviewer years later. “I guess I was kind of a cocky kid, knowing that if the ball went up, I could catch it.”

In 1958, the Giants moved to San Francisco, where Mays was not quite so beloved. Fans crowding into tiny Seals Stadium, the Giants’ first home, instead embraced rookie sensations Orlando Cepeda and Willie McCovey as their own.

“Mays never was to San Francisco what he was to New York,” wrote sportswriter Dick Young. “When the Giants moved to California, the San Francisco fans saw Mays as ‘of’ New York.”

The Giants moved into cavernous and windy Candlestick Park in 1960, robbing Mays of many home runs that would have gone out in a more typical ballpark.

But Mays still possessed extraordinary skills and in 1962, carried the Giants to another playoff win over the Dodgers and into the World Series.

The series was a seven-game spellbinder won by the New York Yankees when Bobby Richardson speared a line drive for the final out of the game with Mays on second base, representing what would have been the winning run.

By the late 1960s, Mays was slowing down. In May 1972, he was traded to the New York Mets and made a final World Series appearance in 1973, his last season, when the Mets lost to the Oakland Athletics in seven games. He retired later that year.

In his book “Willie’s Time,” baseball writer and historian Charles Einstein wrote:

“The lights were hot and the cameras rolled and you knew Willie was there because you heard that laugh. Came The Automatic Question: ‘Who was the greatest player you ever saw?’ His answer was prompt enough: ‘I thought I was.’ There was merriment in his eyes as he looked around the room. ‘I hope I didn’t say that wrong.’”