James Cracknell sometimes refers to himself as “the man who used to be James Cracknell” or “the man who is almost James Cracknell”. Like so many people who have experienced traumatic brain injuries, he underwent an extreme personality change. James Cracknell is the man who won two Olympic gold medals, rowed with the legends Steve Redgrave and Matthew Pinsent and took on superhuman endurance challenges with his friend the broadcaster Ben Fogle. The man who used to be James Cracknell is the product of the 2010 road traffic accident that almost killed him when he was hit by a petrol tanker while cycling in the US. Severe damage to his frontal lobe left him delusional, angry, incoherent, amnesiac and uncoordinated.

Fourteen years on, he has made an astonishing recovery and is running for parliament as the Conservative candidate for Colchester. He might not be the Cracknell of old, but he is closer to it than many ever thought he would be. In one way or another, the 52-year-old has been competing in first-past-the-post races all his life. Now, he is approaching another.

We meet on the bank of the Thames in west London at Crabtree Boat Club, which is another part of his recovery story. Crabtree is a club for University of Cambridge alumni. In 2018, Cracknell enrolled at Peterhouse to study for a master’s in philosophy in human evolution. A year later, at 46, he became the oldest rower in the Boat Race’s history – by 10 years – when he was part of the Cambridge team that beat Oxford.

It’s a hot, sunny day. He offers me a beer from behind the bar and tells me how satisfying it was to row with that team, some of whom weren’t even born when he won his first Olympic gold medal in Sydney in 2000.

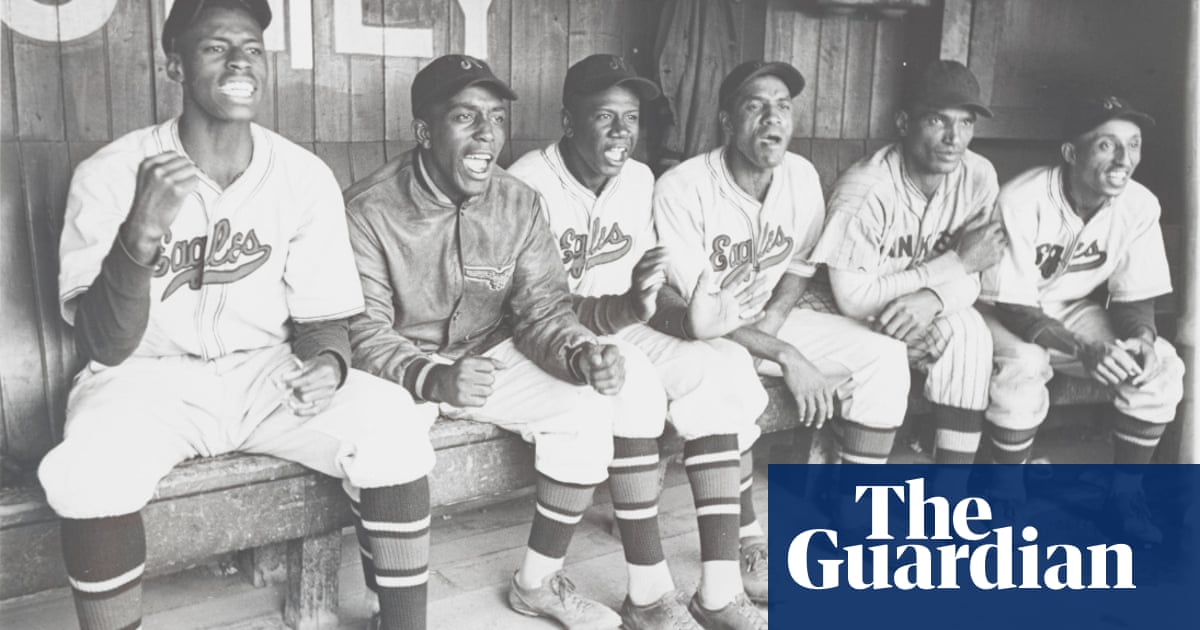

In 1996, at the previous summer Games in Atlanta, Team GB had performed disastrously, winning only one gold medal (for Pinsent and Redgrave in the coxless pair). It was the worst British performance since 1952, with Team GB finishing below North Korea, Algeria and Kazakhstan. It prompted radical changes in the management and funding of British sport.

Rather than reducing the pressure on Cracknell, this increased it. The rowers had been Britain’s salvation in 1996 and were the only safe bet in 2000. Indeed, Redgrave had won gold medals at the previous four Olympics, starting in 1984. He would become the first Olympian to win five gold medals at successive summer Games if Cracknell could help his coxless four bring it home.

Cracknell had his own worries, too: he had been selected for the previous two Olympics, but had missed out because of injury and illness. He was about to make his Olympics debut at 28 – an age when many Olympians begin to think about retirement.

Cracknell says his greatest memory is not winning gold, nor the celebrations after, but being told three years earlier that he had been picked to row alongside Redgrave and Pinsent by the coach Jürgen Gröbler. “The highlight of my career was when Jürgen sat us down in 1997 and said: ‘Right, this is the four.’ Steve and Matt put their Olympic reputations in my and Tim Foster’s hands. For those two to put their legacy in your hands was …” He trails off. Cracknell often doesn’t complete sentences, but here he doesn’t need to. He was elated. “I thought: ‘Right, now there’s a path ahead, I’m not going to let any fucker take this seat.’”

It meant so much to him because Cracknell was being given a second chance. He had done his best to sabotage his career before it had even started. If he had been sensible, luckier or less hubristic, Sydney could have been his third Olympics, rather than his first. At 18, he won the junior world championships and was set for a place in the 1992 Olympics team in the men’s coxed pair, but he broke his shoulder playing rugby. Although he had worked his way back to fitness by the Olympics, he was told he could go to Barcelona only as a reserve. Cracknell wasn’t happy with that.

“I was 19 and I said: ‘Well, I think I’m better than them.’” Being a reserve, he says, “is not like being in the squad – you don’t get subbed halfway if it’s not going well – and I said: ‘I don’t want to go.’ Then they said: ‘Well, you’ll never row for Britain again,’ and I was like: ‘It’s a boring sport, I don’t want to.’”

Did he really think rowing was boring? “It’s a boring sport in that we only race four times a year. There’s three World Cup races, Henley Regatta and then the world championships or Olympics, so apart from the selection races, which are internal, we’d only have four races. And the training is relentless: seven days a week for six weeks and then a day off. But the actual racing is amazing; I was being flippant. I clearly enjoyed it and wanted to do it, but I was a stroppy teenager. I may have been completely wrong that I was better than that person and that person, but you’ve got to have belief in yourself – and I did.”

He went on holiday to Canada, from where he watched Redgrave and Pinsent win the coxless pair and the brothers Greg and Jonny Searle win the coxed pair. It hurt. He realised how petulant he had been, how much he wanted to compete at the Olympics – and that he had probably blown his opportunity with his big mouth.

“I rowed with Greg in the under‑18 world championships and we won together. Then watching him win made me think: ‘OK, I can do this.’” The problem was he was now out of favour, had lost his funding and was regarded as a liability. He also felt bad for another reason – his parents had bought their tickets for Barcelona months earlier and he had let them down.

Cracknell was determined to fight his way back into contention. He made the sacrifices that so many Olympic champions make – trained till he felt sick, ate till he felt sick and missed out on parties, nights out and holidays. While his friends had begun to earn decent money and save, he was still a poor aspiring Olympian: “Your mates are buying houses and you’re still renting a room.” But it was worth it, he says. “You’re still doing what you want to do.”

Like many Olympians, he became boring and solipsistic. He trained, ate and counted his calories, all 6,000 a day. It was tough for his friends and even tougher for his partners. “You’re tired, grumpy, you eat loads and then you’re away all summer. You’re not the world’s best boyfriend,” he says.

His efforts paid off. Cracknell was selected for Atlanta in 1996, but got tonsillitis at the last minute and was unable to race. Again, his parents had bought tickets and flown out to the US. “I didn’t have a mobile phone then, so I couldn’t tell them: ‘I’m not going to race tomorrow.’ They didn’t know until the boat appeared round the corner on the way to the start.”

It was after this that his father asked him a serious question. “My dad said: ‘Look, we bought tickets for two Olympics and we’ve yet to see you get to the start line. Are you sure you want to carry on?’” It made Cracknell all the more determined.

Sport wasn’t the natural career choice for Cracknell. He wasn’t obviously gifted, he says. At Kingston grammar school in south-west London, he played a bit of rugby, but the physicality soon put him off: “I only played till 13 or 14. I was quite tall, so I got put up a year, and everyone had hit puberty and suddenly it was just no fun getting beaten up.” As for cricket, he didn’t excel as a batsman or bowler and found it boring standing in the outfield for much of the day doing nothing. He liked football, but didn’t have a great aptitude for it.

But he loved watching sport. The first Olympics he took notice of was in Los Angeles in 1984, when the British decathlete Daley Thompson successfully defended the gold medal he had won in Moscow four years earlier. Everything about Thompson appealed to him – he was a maverick, he didn’t take himself too seriously and he appeared to be the underdog in a fierce rivalry with the giant German Jürgen Hingsen: “This small guy beating this massive German guy was really appealing.” In fact, Thompson is 1.84m (6ft) tall, while Hingsen stands at 2m (6ft 7in).

He loved the way Thompson whistled the national anthem and always wore a tracksuit, whatever the environment. “Daley’s from around here and he came to Kingston borough sports day in 1985,” he says. “He brought his medals down and seeing him with them was an inspiration. After a rugby or football game, you just got a plate of sausages and beans, but he had these amazing medals. That’s much better than you get for any football match.”

One day, Cracknell was playing cricket at school – fielding – and as bored and distracted as usual. “Our playing fields were near Hampton Court, close to the Thames. I was standing in the outfield, hoping the ball didn’t come to me, and I watched a boat go past with everyone doing something at the same time. I thought: that’s much more fun than what I’m doing standing here.”

So he took up rowing. “Apart from swimming, it was the one sport that I found the more you practised, the better you got.” Five years later, he was junior world champion.

When Cracknell eventually made his Olympics debut, in Sydney, eight years later than planned, he knew he had to win for Redgrave. There was so much emotional baggage invested in Redgrave winning his fifth gold at his fifth Olympics; as the newcomer, Cracknell was aware that, if the team lost, he would probably be held responsible by the public.

Sure enough, they won. How did it feel? “Relief, frustration and then real elation. We didn’t have a good race and the Italians came storming back at us … so that was frustrating. And then those emotions go and you enjoy it.”

What does he think he brought to the team? “Never being satisfied! That was partly because I’d missed two Olympics. I was with Steve in his last Olympiad and I felt it was important to emphasise that what was good enough in ’96 would not be good enough in 2000 and no matter what he’d already won, this was the one we needed to win,” he says. “I was relentless at pushing. So if you spoke to him, he’d just say I was really annoying and never satisfied and always negative. But I didn’t want to get to the Olympics and think: if only I’d said that, if only I’d done that. So I’d rather they hated me and we won than they loved me and we lost.”

Cracknell adored being part of that crew. He looks so proud in the team photo after they won in 2000 – tanned and blond, his gold medal hidden by the union flag he is wearing like a scarf. At 52, he is little changed – washboard stomach, perfect teeth, thick, curly locks streaked with blond; Darcyesque. Almost a quarter of a century on, he still seems awed by Redgrave and Pinsent – and honoured to have rowed with them. “There was nobody in the world I’d have switched anybody in my boat for,” he says. “There was that ultimate trust there.”

Four years later, at the Athens Olympics, he raced again in the coxless four. Redgrave had retired. Cracknell teamed up with Pinsent, Ed Coode and Steve Williams. They won gold again. “We were ahead of the Canadians to halfway, then they came through us, then we came back to them and then they came back at us. We crossed the line and I remember looking back and they drifted ahead of us. And I was like: fuck, we’ve lost. And then the union jacks all started waving in the crowd.” What did it feel like when you saw the flags? “It was a genuine surprise. We couldn’t believe we’d done it.”

Early in 2006, Cracknell retired from competitive rowing with a perfect Olympics record – two events, two gold medals. Between 1997 and 2002, he also had a flawless record in the world championships – six events, six gold medals. I ask if he felt vindicated. Did he say to his father: “See, it was worth it!” He smiles. “After Sydney, Dad said: ‘You can get a proper job now.’ Was he being serious? “Yeah, I’m sure he meant it.” Cracknell says his father, an accountant, has always measured achievement in spreadsheets and, with some justification, regards rowing as “a bad financial plan”. The time he remembers his father being most obviously proud of him was when he got a private pension.

Like so many successful athletes, Cracknell felt lost when he retired. “I’ve never been in the army, but maybe it’s like coming out of the army. I’d rowed for 49 weeks a year for 15 years, so you’re quite institutionalised as to how your year’s structured, then you’re suddenly de-institutionalised,” he says.

He no longer knew what to say when people asked what he was doing. He wrote for the Daily Telegraph, but he felt it was over-egging the pudding to call himself a journalist. He was on TV, but he thought it was pushing it to call himself a presenter. “I found the toughest question to answer was: ‘What are you doing now?’ Nothing I was doing felt as important or as worthwhile in my head as saying: ‘I’m training for the Olympics.’ It gets you out of a whole load of answers to other stuff, whereas suddenly you haven’t got that. And then you start to question yourself. What am I actually doing? That’s when it really comes home – actually, I need to do something.”

He and Fogle competed in the 2005-06 Atlantic Rowing Race, finishing second in the pairs division. Their adventure was accompanied by a book and a BBC TV series called Through Hell and High Water. This was the catalyst for a new career – as an endurance champion. The more extreme the events became, the better he was at them.

His struggles made for great television. In December 2008, Cracknell, Fogle and the doctor Ed Coats came second in the inaugural Amundsen Omega-3 South Pole Race. Their 481-mile journey, during which they endured frostbite, pneumonia and extreme exhaustion, was turned into the BBC series On Thin Ice and an accompanying book.

In August 2009, Cracknell attempted to break the non-stop Land’s End to John o’Groats mixed tandem world record along with the Olympic gold medallist Rebecca Romero. Cracknell had always enjoyed cycling – as a child, he says, it gave him his first taste of freedom. It was also a vital part of his rowing training. He and Romero were on course to break the record by more than three hours, but they had to give up just after passing Johnstonebridge in southern Scotland when Romero sustained an injury.

Cracknell was now less insecure about his post-rowing life. He was establishing himself as one of the world’s great endurance champions, a popular TV personality and a successful author and journalist. Then, suddenly, his world came crashing down.

On 20 July 2010, Cracknell was cycling along a quiet stretch of road outside Winslow, Arizona, as part of his attempt to cycle, row, run and swim from Los Angeles to New York within 18 days. It was 5.30am when he was hit from behind by the wing mirror of a petrol tanker travelling at 70mph and suffered a contrecoup injury to the frontal lobe of his brain. He says he survived only because he was wearing a helmet. Helmet or no helmet, his survival was a miracle. He remembers little about it, nor much about the next couple of years.

In 2013, Cracknell and his then wife, the broadcast journalist Beverley Turner, wrote a joint memoir called Touching Distance, which tells the story from their own perspectives. Cracknell is a reliable narrator of his childhood, his career, his retirement and his mastery of epic endurance events. But the book relies on Turner to tell the story of what became of him after the accident – and it makes for painful reading.

When he was hit by the tanker, Cracknell’s brain swung forward, smashing against the inside of his skull and causing severe internal bleeding. He was put in an induced coma. Turner received a call telling her that she should leave for the US immediately. She assumed she was going out to say her goodbyes to her husband, if she got there in time.

He recovered, but the new Cracknell was a very different man. He emerged from the coma talking like an aristocrat. Turner had previously regarded him as terse and introverted. Now, he was loquacious and egocentric – he couldn’t stop talking about himself. Like so many people who experience traumatic brain injuries, he was unstable, irrational and occasionally violent. He lost his sense of smell and taste. He was impatient with his family; for a while, they were terrified of him.

In the book, Turner describes an awful moment when he grabbed her neck and tried to strangle her. She thought he was going to kill her. “James is an evil caricature of himself,” she wrote. “This angry, unkind and aggressive man is my new husband.” She mentions that 75% of married people who have a brain injury end up getting divorced. Six years after the book was published, so did Cracknell and Turner. Two years later, in 2021, Cracknell married Jordan Connell, an American woman he met at Cambridge while they were studying. She had no idea that he was famous.

Today, he is unrecognisable from the man who emerged from the coma, but also significantly different from the person he was before his injury. I mention the line in the book where he says he used to be James Cracknell. “Yeah. I … it’s …” He trails off. His sentences become stubby and disjointed as he tries to put the change into words, not entirely successfully. “No, there are differences. There are differences and they …”

The spectrum of emotions is reduced, he says. “So obviously the highs are not as high and the lows aren’t as low, if that makes any … so it’s sort of dampened a bit …” He feels as if he should be more grateful than he is. “You have to remind yourself how lucky you are; you know, I should be enjoying this more, I was in a coma and a day away from …” Again, he trails off.

Was it tough to read what Turner wrote about him in the book? “There’s so many things that you don’t talk about with your partner until they’re laid out like that. It is not the easiest read. But I wanted us to be honest about things,” he says. One of the things he struggled with most was people telling him to lower his expectations, to accept that he would not be able to reach the levels of achievement he had in the past.

If anything, he set himself higher targets than ever – studying behavioural science at Cambridge, being the oldest rower in the Boat Race. He wanted to do it for himself, he says, but also as a way of stopping people asking questions. “If I could do the Boat Race after so many years of having not rowed, and secure an MPhil, all the questions of: ‘Are you OK?’ after the accident would be gone – from myself and from other people.” The year at Cambridge saved him, he says. His confidence returned and the world opened up to him again: “If I hadn’t had that, I don’t know where I’d be now.”

And where he is now is truly remarkable. In a week and a half’s time, Cracknell could be the Conservative MP for Colchester, which had a Tory majority of 9,423 in the last parliament. He first stood for election in 2014, failing to win a seat in the European parliament. Cracknell would not be the first British Olympic medallist to become an elected Conservative. Colin Moynihan won a silver medal in 1980 as cox for the men’s rowing eight before becoming an MP in 1983, while the 1500m double gold medallist Sebastian Coe (1980 and 1984) was in the Commons between 1992 and 1997. Both are now peers.

At the time of writing, the Conservatives are about 20 points behind Labour in the polls. Cracknell knows he has a tough fight on his hands, but he is convinced he has the can-do ambition to succeed. “I want to be part of a government that helps people release their potential and sorts their problems out. I think the other two main parties are very quick to impose limits on what you can and can’t do. And whether it be recovery from the accident, or in sport, or starting a business, I don’t believe that. If I’d listened to people setting limits on me after the accident, I would never have got anywhere.”

His politics, he says, have been shaped by personal experience. In 2007, a year after he retired from rowing, he started a sports consultancy and events business. He believes excessive red tape proved a barrier to success and would like to change that. He has always been passionate about the health service, because his mother spent her working life as an NHS physiotherapist; he wants to help change its focus from cure to prevention.

Of course, there are significant differences between winning an election and a boat race. As a rower, popularity is irrelevant to success. In Colchester, he has to convince the greater part of 80,000 people that he is the best candidate. He also points out another difference, this time with a smile. At the Olympics, he was part of a tiny team, all rowing in the same direction. “Now, it’s a massive team, in which not everyone seems to be rowing in the same direction.”

But he insists he is not prepared to win by parroting a party line. What will he say to voters who tell him that the Tories have had 14 years in power and left the country in a mess? “Well, I’m not going to stand up and blindly defend things that have gone on in the past that I don’t agree with. I’ve a pretty strong moral compass, and believe in right or wrong, and there’s things that have been wrong.”

What hasn’t he agreed with? “Behaviour during lockdown.” He says he was disgusted by Partygate. “The arrogance of people imposing the rules thinking they didn’t have to abide by them and thinking they could get away with it. I’m just going to be really honest if I agree with something or not. That may annoy some people in central office, but I’m fighting to represent the people of Colchester and they’re my priority.”

Cracknell was criticised in April 2020 for seeing his parents in their garden at a time when households were not allowed to mix other than to deliver essential supplies to vulnerable people. He defended himself, saying he was dropping off food and that he remained socially distanced throughout.

He cites his former rowing coach Gröbler, who Cracknell says always spoke plainly: “He didn’t care if he was unpopular. I still talk to him now and ask his advice, because I get a straight answer. That is what I would bring – a straight answer.” He pauses and acknowledges that it’s a high-risk strategy. “I know it’s not great to be unpopular as a politician, but you’ve got to give a straight answer.”

Feelgood stories are few and far between in this election. If Cracknell does get elected, it will complete a remarkable comeback for a man who owes his life to a helmet and a huge amount of luck. We have talked about his many achievements – the endurance feats, the books and TV shows, the world championship triumphs, the two gold Olympic medals. In a few days’ time, he hopes to become an MP. What is he most proud of? “My recovery,” he says, without missing a beat. “That is my greatest achievement.”