Artists should see the advance of AI technology as an opportunity and not a new existential threat for creativity, according to the team behind Tate Modern’s new tech-based show.

Catherine Wood, the museum’s director of exhibitions and programmes, said the Electric Dreams exhibition showed the decades-long relationship between artists and technology – and the fact the two worlds would probably always be intertwined.

The exhibition, which opens on 28 November, will include more than 150 works and feature 70 artists from around the world.

“As a museum, we wanted to say this is not a new conversation,” she said. “It’s not a new existential threat for creativity. Humans and artists have been grappling with these questions for a long time so we wanted to give the long view on the social, existential and artistic questions around uses of technology to make art.”

Lots of the technology on show is decades-old and at least one piece, Otto Piene’s Light Room (Jena), in which light is beamed into a darkened room to create “sculptures”, has never been seen in Britain before.

Electric Dreams starts in the 1950s and spans the “pre-internet” age, although Wood says the artists were consumed by very contemporary concerns about technology, such as how it would be used and by whom.

Wood said: “Art has never just been about crafting images or making imaginative pictures, all the artists in the show are grappling with their being and the technology is a prosthesis or a tool and how those two things come together is what the show focuses on.”

Electric Dreams features art that sounds surprisingly contemporary, such as Harold Cohen’s paintings that were created by “drawing machines” using AARON technology that is widely regarded as the first AI technology for making art.

There are also “immersive” pieces by the likes of the Venezuelan artist Carlos Cruz-Diez and the German duo Monika Fleischmann and Wolfgang Strauss that were early forerunners to the Lightroom shows.

As with contemporary immersive work, those early pioneers were accused of engaging with a fad that would not last, but Wood says they were on the bleeding edge of what was possible and are still relevant.

“At the time with Harold Cohen, people did think it was gimmicky and it was marginalised. People were suspicious but from this vantage point he was a real pioneer and a visionary,” said Wood of the artist who represented Britain at the 1966 Venice Biennale.

“The younger generation are not going to grow up with paint on canvas, they’re totally entangled in the digital environment and looking back at these people who were grappling with it when it was very lo-fi.”

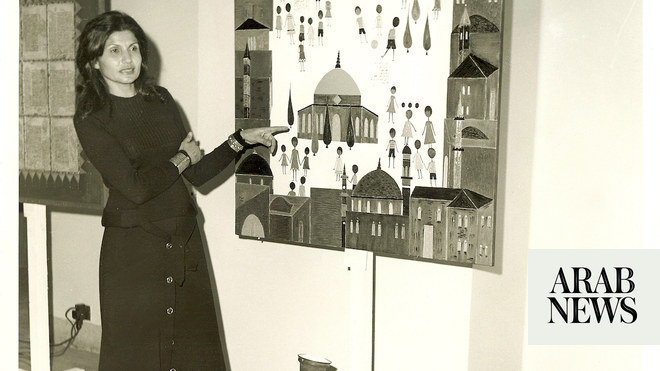

Other artists have a contemporary feel, not because of the work they created but because of their approach. Wood cites the example of Atsuko Tanaka, whose Electric Dress from 1956 is one of the oldest pieces in Electric Dreams and shows how Japanese artists were prepared to take risks and pioneer new styles.

“It was partly the technology in Japan but it was also the attitude,” said Wood. “The Gutai group she was part of was making the process of making art a theatrical spectacle and making it visible in ways that feel completely philosophically natural in our age of sharing everything on social media.”

Wood said one of the biggest challenges in assembling Electric Dreams was getting the old technology to function. She said Tate’s “time-based media team” had been trying to get the hardware to work as well as others such as the Cohen drawing machines.

“They need quite a lot of coaxing,” she said. “It’s often a question of do you preserve the object at the expense of it being able to act? We need these things to be actually working and acting. We want them to be interactive.”

The debate about artificial intelligence and art is a contentious one. There have been several class-action lawsuits in the US, as artists take legal action against AI companies claiming their work has been used, often without permission.

This year Ai Weiwei told the Guardian art that could be easily replicated by artificial intelligence was “meaningless”. Asked if that applied to great masters who had a defined style, such as cubism, Ai said: “I’m sure if Picasso or Matisse were still alive they will quit their job. It would be just impossible for them to still think [the same way].”