Anne Enright: ‘She was all in, every time’

O’Brien blew open the possibilities for Irish fiction, not because of the taboos she broke but because she had broken them as a woman. In 1960, her first novel The Country Girls was burned in the market square of her home town of Scarriff, and every Irish woman who has published since is indebted to the hurt she took on there.

O’Brien’s persona was a mixture of steely determination and an old-style feminine vulnerability. She seemed frightened of many small things – she never learned to swim or to drive, for example – but was unafraid when it came to speaking the truth. She had a beautiful speaking voice and used it marvellously well. Lyrical, playful and passionate, her conversation had a self-replenishing fluency. There were no half measures for Edna: she was all in, every time.

O’Brien described herself as a mere conduit for her work – as though writing were a kind of swoon – but in truth she was incredibly industrious and deliberate in her methods. Her work is interested in deep psychological or primal realities, and this always set O’Brien at odds with the ideological and the mainstream. Though she wrote about women’s lives and loves, she was uneasy with feminism. Her middle work is interested – and not always in a good way – in male brutality. Everything she did showed the same vividness and facility but she was stylistically curious, porous to the contemporary and unafraid to change.

The last novel Girl, is among her freshest. It is set in Nigeria, to which she travelled, in her late 80s, for research. O’Brien kept writing because she needed the money, she said, but there are easier ways to write a book. The truth is she wrote because she was compelled to the page. Like many artists, her problems were designed to ensure production. Frail and indomitable to the last, she lived alone and made her own way.

Ireland’s response to her early novels wounded O’Brien deeply. Artistically, she was also interested in suffering, in getting to the place of greatest hurt. For some, this was a kind of invitation. Up to recently, in Dublin, you knew where you were when someone sneered at her persona or her work. You could also tell when that all started to shift, when she became unassailable and it became apparent some tide of misogyny had been finally turned.

This change buoyed her last years and O’Brien became more trusting of her home country. Still, there is no doubt she would not have survived as an artist in 20th-century Ireland; a country she loved passionately and spoke about with melancholy all her life. Her spirit would have been quenched; the culture would have reduced and traduced her. Most of her adult years were spent in the close exile of London and this sense of impossible proximity made her work more central to the tradition that her voice had once changed. She met her moment. It is from such great tensions and difficulties that icons are made.

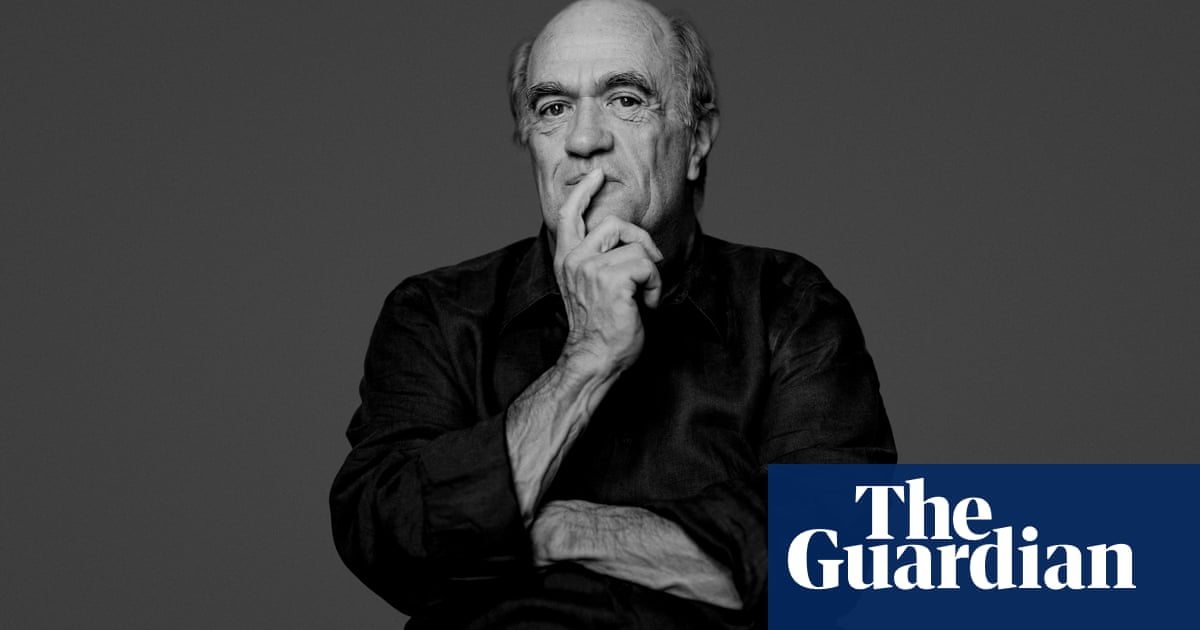

Colm Tóibín: ‘Instead of taking revenge, she set to work’

On the top of the small wardrobe in my parents’ bedroom, over to the right, three paperbacks were hidden. This was before the draconian censorship laws were taken off the statute books in Ireland. The three books were banned novels – The Dark by John McGahern; Couples by John Updike; The Country Girls by Edna O’Brien.

In the conversations I had with Edna over the years, I never told her about finding these books. It would not have interested her much. Writing had brought trouble; she took no pleasure in being notorious in small Irish towns in the second half of the 1960s.

She had been brave. She knew that. And she had been original in the tone she used and the subjects she explored. That interested her more, but still not too much.

What Edna really wanted to talk about was style, how style works in sentences, how style in prose is a way of transforming the self and the world.

Again and again, she would come back to the figures who mattered most to her – Virginia Woolf and James Joyce and WB Yeats and TS Eliot. She was fascinated by how elements of their lives had appeared in novels and poems, how they had been transformed from merely autobiography into something grander and mysterious.

Often, I tried to break the intensity of these discussions with gossip from Ireland. But Edna knew Ireland better than I did; she made it her business to know what was going on in Ireland and was in regular touch with some of the leading players in Irish political life. Minor gossip didn’t really concern her.

Once her sons were grown up, I think she began to care deeply about the quality of her own solitude. She wrote with sharp insight in novels of her middle period about being alone.

The spiritual elements in O’Brien, however, could give way to quick wit and a great worldliness. In a brilliant obituary she wrote of her friend Jacqueline Onassis, she could easily have been writing about herself. She wrote of Jackie’s “breathless enthusiasm, a certain giddiness late at night, a passionate love of clothes”, and added: “But the barriers which she built around herself betray a woman who had espoused self-preservation from the start … Distance and distancing were central to her.”

O’Brien’s achievement was to find a style to match what was intimate and pressing with what was elusive and distant. There is a moment in her novel Time and Tide when the protagonist Nell Steadman has to go to court to fight for the custody of her children.

While O’Brien could have wrested immense drama out of the actual court hearing, she made her great scene not from the day in court but from the day before the hearing when Nell goes on her own to get a sense of the atmosphere in the place where her fate will soon be decided. This was a brilliant strategy. Instead of courtroom drama, we get the fragility of Nell herself, we get the scene imagined, foretold, rather than spelled out.

This, then, is what O’Brien came to London from Dublin to do. She had, in effect, been driven out of Ireland. Instead of complaining or taking revenge, she set to work. Since she had already disturbed the peace, then the task was to restore harmony in her prose-style and then see how much glittering energy she could create by varying the tone, changing the pace, adding to the drama.

She knew as soon as she started that this – getting it right – would be worth doing for its own sake. And that is her great accomplishment.

Megan Nolan: ‘Edna had a relentless interest in others’

I met Edna O’Brien in 2012 when I was working as an assistant stage manager in Dublin on a production of The Country Girls. I hadn’t read the book before beginning the job and took it to the pub to glance through the night before rehearsals began. Five hours later, I was still there, having finished the thing and turned right back to the beginning.

Her writing instantly did away with a plethora of ideas and prejudices I didn’t even know I had been hosting, ideas about what way a woman wrote, ideas about how an Irish person wrote. Perhaps most vitally, she did away with my perception of seriousness – that it was a big unwieldy thing one must approach joylessly and with intellect rather than emotion. I found in her writing a profound intelligence which was spurred on rather than distracted by a tangible, fizzing joy. She seemed from that beginning and right up until her final published works to be driven by a relentless interest in others and in what she observed.

The body of work – so consistently surprising and beautiful and courageous – is well enough on its own basis to cement her in the canon of Irish giants who changed everything for the rest of us. But there is something special about Edna the woman for pretty much any female Irish writer I know, a beacon of a particular kind of brazenness and defiance which serves to guide our aspirations.

I hadn’t yet begun to make anything of my own writing when I encountered her in person. I had given up on the idea after a bad spell of years in my late teens and early 20s. Meeting her, for the brief moments I did when she breezed glamorously through the rehearsal rooms and theatre, was an electric reminder of what I was missing and what I wanted. There was a feeling of meeting a person of whom it could be said: her life was not the least of her art.

Eimear McBride: ‘She had an eye for vanities and pomposities’

With Edna’s death one of the last great lights of the golden age of Irish literature has gone out. Her first novel arrived in scandal and her last leaves her beloved, but her work has weathered every season in between as only the very best can. This was because Edna was an honest writer, always true to her finely attuned ear and instincts, in a way few dared, and dare, to be. The result is a rich and varied body of work, with her jewel-like short stories, plays and poetry all strung between the great heights of her novels.

From her unforgettable debut The Country Girls in 1960, to the high modernism of 1972’s Night, her turn to politics in 1994 with House of Splendid Isolation and on to her last published novel, the haunting Girl, in 2019, she explored the intricacies and complexities of living in a woman’s body while moving through a man’s world, with all the joy and shame, desire and danger that experience entails.

Of the many qualities overlooked by the literary bro culture into which she was obliged to publish was the exquisite calibration of her prose, its intense beauty and capacity to richly convey emotion. Too often dismissed as hysterical, and always presumed to be autobiographical, critics rarely picked up on how funny her writing was. She had a rare eye for observing secret vanities and pricking pomposities.

She held social niceties in low regard and sacred cows in none. And readers loved Edna, which I frequently had the pleasure of witnessing in person. For many women, this was for the voice she gave them and for many men, the insight she shared. But for all, it was for the deep joy her writing gave and the courage her life displayed. I will miss her. Her great work and her equally great self changed me, and all of us, for the better, for sure.

Alex Clark: ‘Her conversation was invigorating, bracing and irresistible’

Journalist and critic

Writers are under no obligation to be charismatic: the page is the thing, even in the era of public appearances and social media. But sometimes, there is a striking consonance between the person you meet and the work you read, and so it was with Edna O’Brien, whose poetic prose required a kind of surrender, and whose physical presence was equally powerful. I confided my nerves about interviewing her at a large public event some years ago to the writer India Knight, who reassured me that she would “chat like the wind”, a remarkably apt description of someone whose conversation came in the full range of gusts and zephyrs, invigorating, bracing and irresistible. You just buckled up and tried to follow its changes of direction.

None of which is to suggest that there wasn’t a considerable amount of O’Brien you didn’t see. Beyond her immense generosity and candour, there was always a sense of great intellectual and emotional depths held in reserve, waiting for her to wrestle with them at the desk. She made it look as if the words tumbled urgently from her mind, but they did not.

Away from that desk, she was a captivating mixture of grandeur and irreverence. I once went to her house in Chelsea to interview her and Andrew O’Hagan for a piece about friendship for an American magazine. When I arrived, she consulted me anxiously about whether her hair was behaving itself for the photographs; it was a ferociously hot day, and she dispensed inadequately tiny glasses of sparkling water in cut crystal. O’Hagan was on his hands and knees fossicking about at the back of her TV. “You just needed to plug the scart lead in,” he told her when he came up for air. She beamed at me. “He is my chevalier!”