Shortly after Daniel Reisinger’s mum died, the director found himself howling with laughter. “It was the shittest week of my life,” he explains, over a video call from his native Australia. “But I’ve also never laughed harder. We were singing Bette Midler’s The Rose around Mum’s bed, and none of us can hold a tune to save our lives, but we were belting it out and all crying our eyes out and laughing.”

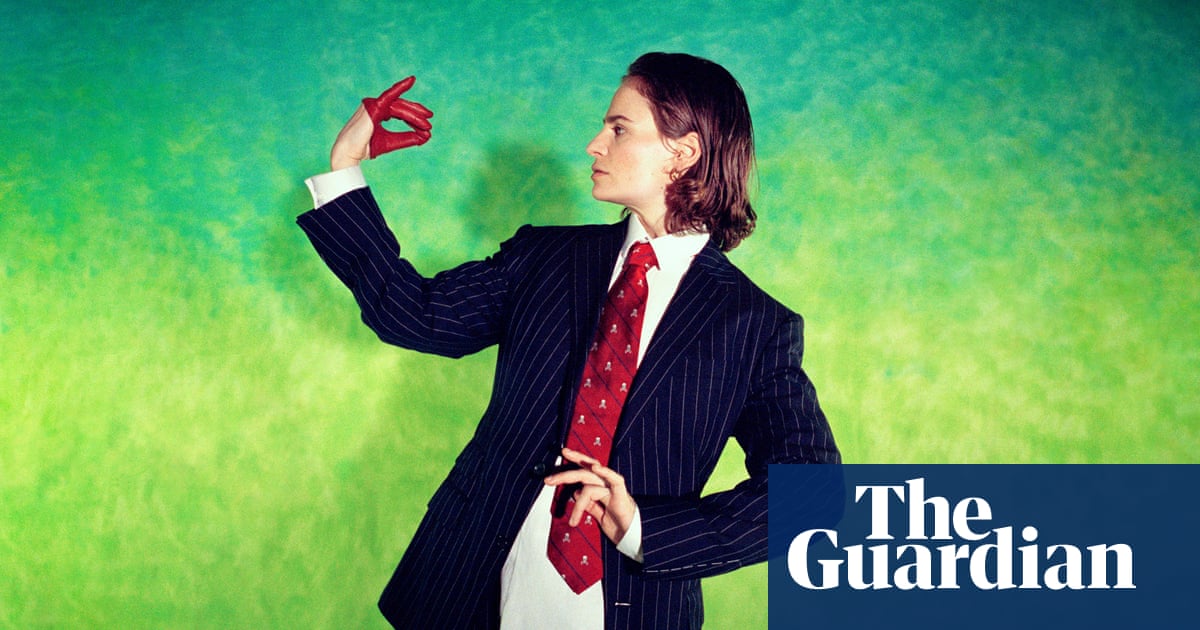

Finding the funny side of grief may still be considered taboo by some, but Reisinger is hoping to change that with his new film, And Mrs. It stars Aisling Bea and Colin Hanks as Gemma and Nathan, a betrothed couple whose big day is thwarted when Nathan dies suddenly just before it. Gemma decides to press on with the wedding regardless, determined to marry her deceased partner (an act known as necrogamy).

The film is especially personal for Reisinger, who was preparing for the film’s pre-production when his mum died of Covid. But he soon realised he wasn’t alone in his grief. Bea’s father had died from suicide when she was a child, Hanks lost his mother in his early 20s and Billie Lourd, who plays Nathan’s wayward sister, Audrey, lost her mother (Carrie Fisher) and her grandmother (Debbie Reynolds) within 48 hours of each other in 2016. As production progressed, the set became a cathartic and often joyous space in which the cast and crew got to share their stories of loss.

“Death was all around the film,” says Hanks when I speak to him on a video call. “I was unfortunate enough to have had several people close to me die around that time, including someone who was like family to me. And then, while we were filming, the queen died! So it felt like all that was very much part of the film’s DNA.”

He says his initial conversation with Reisinger to discuss the movie was scheduled to last half an hour, but the pair ended up embarking on an “insanely personal” chat that reached the three-hour mark. Does Hanks also believe in laughter as a way to deal with grief? “Absolutely. They don’t call it church laughter for nothing; when you’re in church, that’s when you laugh the hardest. And it’s the same with grief.”

The absurdity of grief was fertile ground for laughter on set. Reisinger recalls Lourd telling him how, after her mum and her grandmother died, she was inundated with books on grief, with friends popping around to deliver a new one on a daily basis. “She also hated people saying she’d ‘lost’ her mum. She would say: ‘I didn’t lose her! She’s not wandering around a car park somewhere; she’s dead!’ I guess we say these stupid platitudes because we have no language.”

It makes sense that And Mrs is set in the UK, what with our stiff upper lips. “Does this film make as much sense in Los Angeles, where everyone is in therapy and there’s not as much repressed emotion?” asks Reisinger. “I don’t know! But New Yorkers have seen it and they were bawling their eyes out.”

And Mrs has a keen eye for the details of mourning. We see Gemma in a trance as funeral directors attempt to upsell her on coffin wood. We are reminded of the unavoidable list of admin that has to get done when a loved one dies. Will a grieving family remember to cancel the stripper for the hen party?

Then there is the horribly familiar funeral celebrant, who clearly has no idea what the departed person was like (a cameo from Paul Kaye, who ruins Nathan’s ceremony by making ill-advised Auschwitz jokes and telling the mourners: “Four little letters bring us together and make the world a more beautiful place … MDMA”). Reisinger remembers having to snatch the microphone from someone making an inappropriately personal speech at his mum’s funeral.

More poignant is the way Hanks appears throughout as a ghost-like Nathan, subtly guiding the choices Gemma makes. It reminds us that, even when someone dies, they are not gone from your life.

Hanks says he recognises the experience: “I remember a very dear friend of mine dying and, because of work commitments, I wasn’t able to attend his memorial service. At first, it felt a little as if he had just disappeared. But one thing about him was he always had these beer koozies with him, and so over time I began collecting them, almost as a tribute to him. Sometimes, people will say to me: why do you have so many of these freakin’ beer koozies?! And I’ll say: let me tell you a story about my good friend Rio.”

Reisinger says: “Hey, look, I can’t watch the film. I get to the end and I’m in pieces, you know? I think, once you lose someone close to you, then you start to understand the concept of ghosts. Not necessarily that they’re real as in phantasmagorical, but more like … I’ll be reading something on the Athletic on my iPad, say, and then some memories will pop up with a photo of Mum. That actually just happened like 20 minutes ago.”

Necrogamy may be a fringe idea in the UK – indeed, it’s not legal – but it’s better known in France, where posthumous weddings occasionally take place. Reisinger lived there for a while and cites the moving story of Etienne Cardiles, who in 2017 was granted permission to posthumously marry Xavier Jugelé, the police officer killed by a terrorist on the Champs Élysées in Paris. The film builds on the tension between Gemma’s wish to marry Nathan and her family’s increasing belief that she is mentally unwell and needs to be stopped.

Reisinger says he was keen to highlight how everybody grieves differently; what seems absurd to one person is necessary to another. “Maybe we don’t have the right to say to people that you can’t marry the person you love the most in the world. Is it really more healthy to do the traditional Anglo-Saxon thing and just drink a lot? Or is it more healthy to marry the love of your life? When you put it in that context, which one is the crazy one?”

Reisinger cheerfully admits that the film’s claim that a posthumous wedding could be enacted here thanks to a little-known law introduced during the Napoleonic wars to allow women to marry sweethearts who died on the battlefield is “absolute bollocks”. As he says: “That was just an elaborate excuse to involve Harriet Walter,” who steals several scenes as the lady chief justice, the most senior judge in England and Wales.

The film rides an emotional crescendo, but Reisinger saves a real sucker punch for the credits, which are given over to the cast and crew to memorialise their loved ones. “I wanted it to be their film as well as mine,” he says. I wonder if the film might strike a chord now because millions of people lost loved ones unexpectedly during the pandemic. “We lost 7 million people,” says Reisinger. “And now we don’t talk about it. Maybe we’re going through the Kübler‑Ross stages of grief and right now we’re in denial. There’s still some stages to be worked out. Hopefully, watching something like this can be a way of getting those emotions out.”