Russia is a “mafia state” trying to expand into a “mafia empire”, the foreign secretary, David Lammy, told the UN, nailing the dual nature of Vladimir Putin’s political model. On one hand Russia represents something very old – a world of bullying empires that invade smaller countries, grab their resources and indoctrinate their people into thinking they are inferior. But it is also something very new, weaponising corruption, criminal networks, assassinations and tech-driven psy-ops to subvert open societies. And if democracies don’t act to stop it, this malign model will be imitated across the globe.

Ukraine is resisting the older, zombie imperialism every day on the battlefield, and democracies will have to arm Ukraine and ourselves to constrain Russia properly. But how should we fight the more contemporary tools of political warfare that Russia pioneers? These are becoming ever more prevalent. Globalisation was meant to make us all so integrated that it would diminish the risk of wars. Instead, the free flow of information, money and people across borders also made subversion easier than ever. At the Labour party conference, Lammy indicated that democracies need to work together to stop Russia: “Exposing their agents, building joint capability and working with the global south to take on Putin’s lies.”

We’ve certainly been getting better at the exposure part. This month the UK, US and Canada revealed that RT is more than just a conspiracy-spewing state media; it works with Russian intelligence and security services, and is involved in money laundering, cyber “incidents” against Canadian infrastructure and fundraising for arms. Because the indictment focused on clear criminality, rather than legally opaque ideas such as “disinformation”, justice departments could take concrete action to disrupt the whole system of operations.

But such legal action is just one element of what a “joint capability” needs to do. The audiences that Russian covert operations were targeting are still susceptible to the Kremlin’s messages. Tenet Media, the Maga-media company where the Russians were secretly paying popular YouTubers $100,000 per video to smear Ukraine, reached 16 million views. Their hosts claim they had no idea who was paying them – and their audiences don’t appear to care. Russia operations exploit audiences across the world, playing into historically resonant anti-western, anti-colonial sentiment in Africa and acting as what Lammy has called a “ringleader for a new fascism” that promotes racism in Europe. In Moldova it is spending $100m to subvert this year’s elections and referendum on EU entry, planting dummy candidates to confuse voters and spreading fears that joining the EU will lead to war. All these narratives – from right to left to playing on fear – work.

Democracies will also need to communicate better than the Russians. That means deciding together which issues to focus on, to whom and how.

Consider Odesa, in Ukraine. Russia launches missiles at the city constantly, as well as propaganda to undermine its sovereignty. As the Odesa Decolonization research project (to which I contributed) shows, Russia has spent years pushing out movies and TV shows, maps and speeches that reiterate how Odesa belongs to the “Russian world”. The aim is to weaken the connection between Odesa and Ukraine, and thus make a Russian takeover easier in the eyes of the world.

A concerted effort to push back would first decide on which are the important audiences to engage with – and how to talk to them.

For those who worry less about Ukraine’s sovereignty but more about food prices, you would need to explain that Odesa is the hub of the grain corridor that keeps supplies flowing to the world, especially to the Middle East and Africa, while helping keep food prices under control in the US. If Russia were to capture Odesa it would be able to blackmail the world and control prices. Do we really want a gangster like Putin manipulating the flow of grain at will?

Then you need to decide who should communicate this message. What can each ally do more at home? Which nation in the coalition can best reach a specific global audience? You will need to employ statesmen, current and former, and cultural figures that resonate with that audience; set up cultural events, speak at churches and go on TV shows – with each country bringing its strengths to the effort. The aim is to ensure what Prof Nick Cull of the University of Southern California calls “reputational security”: ensuring that the portrayal of a place is well known enough to help resist aggression. We don’t need to adopt the same tactics as the Russians. Where they do troll farms we can do online town meetings. But you do have to focus and scale.

But joint capability also has to be more about nation states coordinating strategic communication. We need to disrupt the Russian war machine much more intensely. And states are not the only important actors.

One of the great revelations of this war is how independent researchers scouring customs records and other open source data can map networks and, unlike secret services, make the evidence public. Take the Economic Security Council of Ukraine (ESCU), a small team of researchers in Kyiv, who managed to show the US Congress how Russia acquires CNC tools, the complex machines that make weapons. Mapping supply chains is the first step to effective action to weaken Russia’s war machine – not just the dodgy companies that help move equipment to Russia but the origin of unique spare parts, raw materials, the mining equipment that extracts those materials, the lubricants used and so on. It’s a huge job but open source researchers can map this remarkably quickly.

From mapping comes vulnerabilities – where are Russia’s critical supply chains particularly open to disruption? And from vulnerabilities come options for disruptive action. Anti-corruption campaigners can out bad actors in the media. With the right data, companies can stop doing business with dubious intermediaries. The US and European states can create more surgical sanctions. Ukraine can take more direct action.

Russia’s war machine is serviced by a vast criminal network. We have to build our own networks, fusing the flexibility of open source researchers, anti-corruption activists, media, business, treasury departments and frontline states’ special forces.

Democracies have a much richer pool of partners to tap into than dictatorships, which by definition operate in a more closed and dirigiste way. The trick will be to get the democratic swarm to focus its strengths together – something dictatorships are better at. There’s no time to lose. Dictatorships are starting to coordinate more closely. Russian- and Iranian-aligned hacking networks are hitting US utilities and British hospitals. Russian and Chinese companies are circumventing sanctions on military supplies. Their networks of troll farms, hackers, mercenaries and criminal gangs are working ever faster. Can we activate a democratic network to compete?

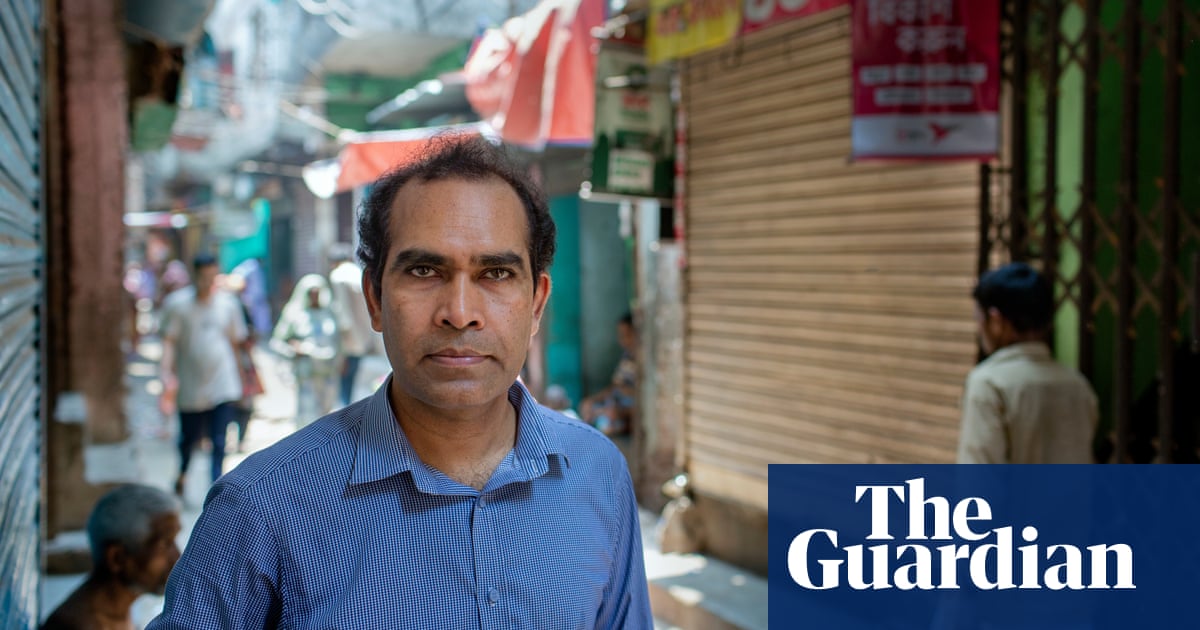

Peter Pomerantsev is the author of Nothing Is True and Everything Is Possible: Adventures in Modern Russia