‘Ihad killed a lot of people in other films,” says Alice Lowe, whose first feature, 2016’s Prevenge, saw her play a pregnant serial killer. “This time I just felt like I should kill myself.” Agnes, the hero of Lowe’s new film, Timestalker, meets many grisly endings. Played by Lowe, she’s pursuing her dream man through the centuries, from prehistoric forests to 80s New York. But in every era, before true love can blossom, her time is cut short. Then she’s reincarnated, ready to try again.

Timestalker is a romance. Or is it? It’s about reincarnation. Or is it? Just as in Prevenge, where a woman grapples with the line between truth and fantasy when she hears her foetus issuing murderous instructions, we’re invited to question what’s real as we’re immersed in Agnes’s muddled mind. The film is dreamlike: scenes have a powdery, shimmery quality and a surreal theatricality. “I wanted it to be delusional, and that you stay in that delusion, you don’t have the bubble burst,” says Lowe. “They’re all trapped. The joke with this is that people can’t change. Even though they’re her dreams, she’s still dying.”

It’s funny, gory, and asks fascinating questions about obsession and the power of the human psyche. “The universe that I try to create with my films,” she says, “is dark, but not so dark you feel nihilistic.”

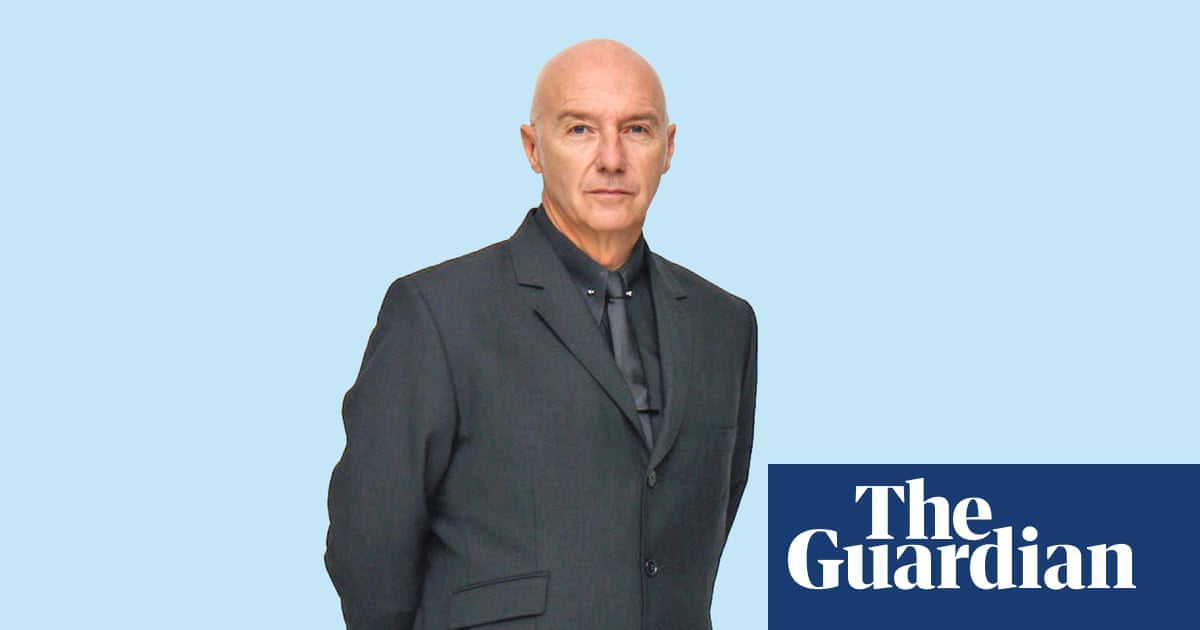

Lowe is a woman of many talents; a writer, director and actor who’s built cult followings across comedy and horror, beginning with roles in Garth Marenghi’s Darkplace and then in Sightseers, which she wrote with Amy Jump and co-star Steve Oram and was directed by Ben Wheatley. Yet, despite this reputation – and the critical success of Prevenge, which Lowe made while pregnant in real life, Timestalker took seven years to complete. “Independent film is in so much trouble,” she says. “I had that sense during the pandemic: so many female directors do not get to make a second film.”

In response to film bosses saying it takes £3m to make a first feature, she has advocated for a greater number of smaller grants to be handed out instead. “There are so many people who just need a first chance to make a smaller-budget film,” she says. “Why don’t we embrace a more punk aesthetic with how we make British films?”

Looking back, the film itself reflects those anxieties. “It’s about reincarnation and hopeless love,” she says. “I think of it as a metaphor for artistic endeavour and chasing a crazy dream. It’s going to damage you, it’s going to hurt you, and you don’t really know if you’re going to get anything out of it. That is my career.” She twisted her ankle on the first day of filming, and worked long hours across a 22-day shoot in Wales, temporarily relocating her family there. “It won’t happen if you’re not evangelically obsessed with the project,” Lowe says. “If you don’t believe in it, no one else can.”

Agnes embodies that obsession as she hunts down her man, despite his lack of interest. At the same time, she herself is pursued by a sinister character played by Nick Frost. When we speak, the furore around Baby Reindeer is at a peak, and Lowe suggests Timestalker is the perfect companion piece for the Netflix drama: a glimpse inside the stalker’s head. “There’s darkness there, but she’s concealing it all with fluffy rainbows and chiffon,” she says. “It’s about the chase. The fantasies are more pleasurable than the actual interactions, because the actual interactions don’t go well. To me, that’s perfect film-maker territory because most film-makers are obsessive.”

Lowe grew up in Coventry, the daughter of two teachers who saw education as the path to success, but also loved watching TV. She got her own tiny black-and-white set as a teenager, and would watch it late into the night, one toe on the power button in case her parents came to tell her off. She’d devour late-night animations, Hammer horror and films like Withnail and I, plus any comedy, but especially Vic and Bob.

She loved art too, but steered towards more academic subjects and earned a place studying classics at the University of Cambridge. She got involved with student theatre, making costumes and sets. Invited to audition for Peter Pan, she instead landed the role of Captain Hook’s sidekick Smee, and played it for laughs. “I was the only girl who didn’t mind looking repulsive,” she says. “I gave myself yellow teeth and spots.”

She continued with devised theatre during university – its loose, improvised approach suited her – then, at the turn of the millennium, began a momentous collaboration. Starring alongside Matthew Holness and Richard Ayoade, with Paddington’s Paul King directing, Lowe became part of the comedy horror universe of Garth Marenghi, performing in two Edinburgh fringe shows that earned an Edinburgh comedy award nomination in 2000, then a win in 2001. That led to their first TV show, Garth Marenghi’s Darkplace, which, 20 years on from its release, remains a cult classic.

Even after this big break, there were signs it might be tougher for Lowe than her male co-stars. “I shouldn’t tell this story, but I’m going to,” Lowe says. “[On] The IT Crowd, all of the boys from Garth Marenghi were given straight offers of main roles, and I had to audition.” She was away working on a show, so the part was given to someone else; she then had to audition for a small cameo. “That typifies my career,” she says. “The opportunities that don’t get thrown your way as a woman. You can be associated with so many brilliant projects, but people will assume it’s got nothing to do with you.”

Lowe has always challenged sexism when she’s seen it. “I’ve always gotten mouthy about this stuff and it hasn’t really helped my career,” she says. “There was a director who said that women weren’t funny. I complained and they fired me. It was the end of that laddie comedy era. They made me feel like I was a mad, difficult woman, but what I was saying was completely rational: you can’t say that women aren’t funny on a comedy show. You shouldn’t be in charge if you think that.”

Lowe appeared in many celebrated 00s comedies, including The Mighty Boosh and Hot Fuzz, but also began making her own short films. She realised that being across every element of a project – from idea to aesthetic to sound – brought a satisfaction she’d been missing.

Now, she brings that devised theatre philosophy to her sets, inviting improvisation and playfulness. “I don’t like to formalise too much what I do, because I get scared that it will actually get worse,” she says. And, as a director, she says “the atmosphere you create is going to dictate how people are treated. Why shouldn’t people be having fun doing it? People make a load of sacrifices. It’s a very antisocial job.”

She says film funding bodies can get “freaked out” when a writer-director wants to star in their own film: “They’re like, ‘Oh, we assumed you’d want Kristen Stewart at this stage.’ Well I sort of do, because I love Kristen Stewart, but also I’m scared of Kristen Stewart; I’m scared of famous people.”

Now, as writer, director and star, she’s able to execute her creative vision without compromise. “I read something recently saying we need to get rid of the auteur, it’s patriarchal and damaging. But can’t women just have a go though, before we get rid of it?” she laughs. “With hundreds of people contributing, you’re operating by what wins the most votes. Everything becomes the same. If you don’t have an auteur, how do we protect against being bland?”

Lowe likes the idea of being “a maverick … a berserker” amid the footsoldiers of the film industry. “I’ve got an anti-authoritarian streak, for sure,” she says. That manifests in her films, where she’s drawn to “flawed heroines”. Yet she’s exasperated by the tendency to read characters like Agnes, or Ruth from Prevenge, as moral endorsement. “Agnes is not self-aware. She’s karmically naive. If you can’t let a woman be that character, that’s really sad. She’s just one character. It’s not instructions.”

There is a particular pressure on female directors, who are vastly underrepresented in the industry, with only 22% of key creative positions held by women in UK film. “You get to this point of like: you are carrying the message of womankind on your shoulders, you have the responsibility to tell us what it is to be a woman. And I’m just like: I don’t want to,” Lowe says. “I’m literally going to do the opposite of what you’re expecting me to do now.”