The first time I encountered Leeroy Thornhill, he invited me around to his place to smoke banana skins. I was only 12 years old at the time – but before you call social services, let me reassure you that this wasn’t a real-life interaction. I was simply reading the sleeve notes of his band the Prodigy’s debut album, Experience, where the peculiar fruit-based invitation was offered up to the band’s fans. Just above it was a photograph of the group sharing a joint. They seemed thrillingly above the law – and the rules of being in a band itself.

For a start, half of them – Thornhill and his best mate, Keith Flint – were employed as dancers. A third member, Maxim, was a vocalist who didn’t seem to appear on half the songs, which left only Liam Howlett to make all the music, a furious collision of breakbeats, helium vocals and space-age synthesisers. It was the kind of outfit you might dream up after a night smoking, well, banana skins. Did they actually do that?

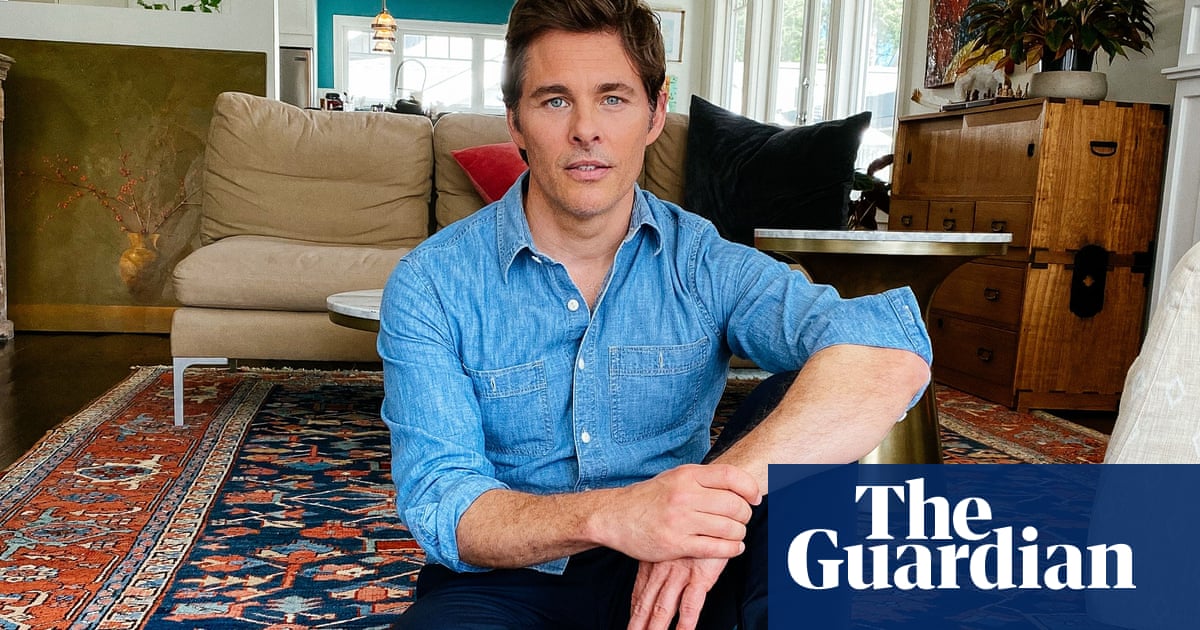

“No!” laughs Thornhill, when we speak via video link from his home in Essex. “Many other things, but not those.” He ponders his band’s corrupting influence on junior listeners such as myself. “We’d have been about 21 at that time. At that age, you’re so far away from the mindset of a 12-year-old. We were just thinking about playing parties. But, as time went on, we’d notice that kids – 13, 14 years old – would be sleeping under cars outside our hotel just so they could meet us. We started to realise that everyone liked it.”

Indeed, as the Prodigy developed, they found themselves appealing not just to ravers but rock fans and festival crowds, too. For the decade Thornhill was in the band (he left in 2000), they went from playing live shows at messy nightclubs in Essex to touring the world and reinventing the idea of how big a dance act could be. The story is told in Thornhill’s new book, Wildfire, which collects hundreds of photographs he has saved – taken by himself, his sister and a couple of others. It’s like a trip back in time – sweatbox venues, ludicrously baggy outfits, not a phone in sight – and plenty of evidence that the band and their fans had the time of their lives. Flint in particular stands out with his wide-eyed mugging for the camera.

The whole thing is a testament to the 90s, when the world felt a little more carefree, hedonistic and ripe with possibilities. Alongside the pictures is a timeline of the band and some comedy anecdotes. You shouldn’t, however, mistake it for a tell-all memoir. There’s no airing of dirty laundry here. And given that it sticks to Thornhill’s time in the band, there’s only the briefest reference to Flint’s death in 2019 (“He left us way too early but his star will always burn bright,” it reads). Today, though, he will be more forthcoming – not just about his friend, but the pressures all men face as they grow older.

Thornhill grew up in Rayne, Essex, and it was through partying in nearby Braintree that he got to know Flint – the pair hit it off immediately. “We were like a little comedy duo right from the off, making a joke out of everything.” After being introduced to the “really shy” Howlett – and discovering that the music he was making himself was even better than the stuff they were dancing to in the clubs – they asked him how he’d feel about putting together a live show with them fronting the operation as energetic dancers.

The aim wasn’t really to start a band. It was just about getting up on stage. At the time, Thornhill had no idea what he wanted to do with his life, although he’d done his electrician qualifications. “My mum was in the Caribbean when I told her that I’d joined a band. She said: ‘Oh good, that’s going to pay the rent,’” he says, laughing. The thing was, paying the rent wasn’t the reason they were doing it. They were more interested in being young and immersing themselves in dance culture.

Clubs were where Thornhill felt at home. He grew up as “one of 10 black people in a community of 25,000”, and, as he was 6ft 6in tall, he spent a lot of his time “trying to stay in the background so I didn’t get shit all the time”.

Trouble was not his thing. “We had mates who’d say they were going to go and do some car stereos, but we’d just be like: ‘We’re off.’” Thornhill remembers going to local clubs where he’d sit and watch groups of people he knew throwing chairs at each other’s heads, “like it was a western!” But the places he preferred to frequent were only about good vibes and dancing. A huge fan of James Brown, he developed his own fast-paced style of foot shuffling.

The band’s live gigs were wild. During a sold-out show in Folkestone, one ticketless fan was so desperate to get inside that he jumped headfirst through a window pane. Thornhill remembers looking up and seeing a shadow coming towards him – the fan hadn’t realised that the venue floor was actually three storeys below. He landed on their equipment and was carted off to hospital. “I wonder what he’s up to now?” Thornhill says. “Wouldn’t be too hard to find him, he’s probably got the mixer buttons still imprinted in the side of his face.”

As the band gatecrashed the charts, purists sniffed that they were selling out the rave scene. The band members found it funny, though – whenever they released a track anonymously on a white label, those same purists would send it to No 1 in the dance charts. But in truth the Prodigy soon outgrew the scene they came from: Howlett’s love of hard-edged hip-hop production and raucous punk energy helped them broaden their fanbase with songs such as Poison and Their Law. When Flint spiked his hair and became a kind of nightmarish, dancefloor version of Johnny Rotten, spitting out the lines to their hit Firestarter, the band went stratospheric.

Thornhill remembers how the glare of the spotlight fixed itself upon Flint: “We could walk through an airport unrecognised, but he’d be getting angry because he had to have his own security guard. He couldn’t go shopping or do anything really. He’d have people camping outside his door – when he opened his curtains there’d be people sitting on his wall.”

One summer, the band were sitting in Flint’s back garden, smoking a joint, when a guy walked around the side of the house with four kids and started pointing at Flint. “It was like he was in a zoo! This guy was saying: ‘There he is, there’s the firestarter!’ We were trying to hide the joints from the kids and looking at each other, like, this is not right. But Keith ended up going into his house to try and find some photos for them to take home. That’s what he was like, bless him.”

Thornhill says he was amazed by how well Flint dealt with the pressure. And although there are some tales in the book of Flint sulking or – on one occasion – losing his temper so badly he ripped the phones from several hotel room walls, Thornhill is adamant there were no outward signs that he was ever struggling with his mental health.

Flint was a thrill-seeker – he loved snowboarding and in later years owned his own motorcycle racing team, Team Traction Control. Thornhill says the rest of the band always half-expected a call one day to say that he had done something reckless, like “falling off the side of a mountain or coming off his bike”. In the book, Thornhill recounts the time when, while they were stoned on a private plane, the pilot invited them all to have a go flying it. Flint sent them shooting upwards into the sky. “We were all freaking out, shouting: ‘Get him back here!’”

But Flint had another side. After his death, the singer James Blunt recounted an experience at the Q awards where Noel Gallagher, Paul Weller and Damon Albarn were all publicly shunning him. “Keith Flint came over, gave me a hug, and said how thrilled he was for my success,” Blunt said. Thornhill’s mum thought the same. “She’d always say: ‘He was such a sweet, lovely guy’, you know what I mean?”

Flint’s death did, of course, hit Thornhill hard. “I love him and I always will. We’ve been to 70 countries, met royalty, seen the coolest things on the planet. So of course we’re sad and heartbroken.”

It’s not just Flint’s death that has contributed to this outlook, but the experience of many of his mates. “A lot of my friends have said, ‘Oh, I thought about killing myself’ and, you know, I kind of reached that point once myself.”

Really?

“I don’t think that anyone prepares men for middle age. When they get to their 40s or 50s and they’ve got families, people don’t explain to them about the pressures, about how everything will crumble if anything happens to them. A lot of the world rests on men’s shoulders but we don’t hear about that. It’s an age where people think they should be getting ready to retire and enjoy themselves, but instead they’re having to get an extra job on Saturday and working from 5am.”

Thornhill says his mates all check in on each other if anyone’s been feeling down. “There’s the old English stereotype of the man being the rock and you don’t talk about your problems – but you have to communicate.”

When the Prodigy were at their late-90s peak, the African National Congress wrote to them asking if they would play in South Africa. The party believed the band’s multiracial lineup would provide a good example in a country still trying to heal the wounds of apartheid. “We never really thought about stuff like that,” says Thornhill. “To us, we were just English, and we were always pretty cool with racial harmony. Maybe we [the English] are a bit worse now.”

The South Africa tour went great; it was the US where Thornhill says he struggled. “It’s the most racist place I’ve ever been. There’d be times down Texas way where they wouldn’t serve me and Maxim – they’d just want to serve the white guys. But even in New York there’d be people in our dressing room ignoring us. Then they’d find out we were in the band and be surprised. They thought we were just gangbangers or something.”

Since leaving the Prodigy, Thornhill has made his own electronic music, and he still gets his party fix DJing at events such as the Messy Weekender festival. But the hectic days in which he sometimes wouldn’t even know which country he was in are gone. The windmill he bought to live in while in the band – “Somewhere I could fit in,” he grins, alluding to his height – has long since been done up and sold on. And he has grownup kids now, a 21-year-old daughter and a 15-year-old son. “I teach them to be streetwise more than anything else,” he says. “And that they should just enjoy their life, because you get out of it what you put into it. But I’m not like a dad. I’m more like a mate, really.”

He’s still in touch with Howlett and Maxim, he says, and was with Flint until the end, too. But if Wildfire makes being in the Prodigy sound like the best possible way to spend 10 years of your life, there’s absolutely zero chance that he would ever rejoin them to relive it all. “You really want to see a 56-year-old man going around the stage like a grandpa at half speed?” he laughs. “That ain’t happening!”

Wildfire by Leeroy Thornhill is published by White Rabbit (£35). To support the Guardian and Observer, buy your copy from bookshop.theguardian.com. P&P charges may apply

In the UK and Ireland, Samaritans can be contacted on freephone 116 123, or email jo@samaritans.org or jo@samaritans.ie. In the US, you can call or text the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline on 988, chat on 988lifeline.org, or text HOME to 741741 to connect with a crisis counselor. In Australia, the crisis support service Lifeline is 13 11 14. Other international helplines can be found at befrienders.org