It was a heart-stopping sight. On 24 April this year, blood-drenched horses galloped through rush-hour traffic in central London, smashing chaotically into a tourist bus and a taxi, before careening along pavements in blind panic. The horses, which serve in the Household Cavalry Mounted Regiment guarding the king, were on their daily morning exercises near Buckingham Palace when loud noises from a building site caused them to bolt and rampage through the capital for more than two hours. Six people were hospitalised with minor injuries, but all the horses survived in what seemed a once-in-a-lifetime event. Then, on 1 July, it happened again. Three regal horses bolted through Knightsbridge, this time fleeing a London bus.

Having just published Hoof Beats: How Horses Shaped Human History, William T Taylor knows a thing or two about horses and he acknowledges the curiousness of the horses’ escape when I call him at his home in Colorado. “The funny thing about our modern world is that horses are so deeply embedded in so much of our culture,” he says. “That grew out of their role in things like transport, communication and agriculture. It’s a powerful example, these military horses. It might take them escaping and running amok for us to think about it, but it has actually always struck me, when visiting London, just what a majestic and dangerous symbol of power and authority they represent.”

Taylor, an anthropologist at the University of Colorado Boulder and curator at the CU Museum of Natural History, explores the deep and ancient links between horse and human in forensic, academic, archaeological detail in his book. He plots the evolution of the horse from the extinction of the dinosaurs and the survival, at the time, of the tiny “dawn horse” – the size and shape of a puppy – which would evolve into the tall, long-legged, magnificent creatures we know today.

Taylor comes from a long line of cowboys. His own choice of work, he says with a sigh, was inspired by an Indiana Jones video game. “Yeah, it’s a real cliche,” he laughs. But it can also be seen as a lifelong quest to connect with his own past because he grew up in a house filled with western kitsch, dressed in cowboy kits at country fairs – and today he goes riding in Mongolia.

He was recently left his grandfather’s tack: saddle, bit, reins.

“At the beginning, it didn’t particularly mean a lot to me,” he says. “But as I got into this work and began exploring, one of the first things I did with my dissertation work in Mongolia was to begin to try to understand, how does this horse equipment work? What is it? I began to dive real deep into the basics of how different configurations of horse equipment work and what they might mean.

“And my grandfather’s horse equipment setup tells me how he was a very direct communicator. This is a piece of my family heritage. I’m trying to restore and revive some of that so that maybe I can actually end up using it myself. This might be a little silly and overly dramatic, but there’s something special about connecting to the past through objects. And, of course, I would be a terrible archeologist if I didn’t believe that!”

As we speak, Taylor, a lone-ranging bachelor, is preparing for a fresh field trip to Mongolia, where much of his research is carried out. His flight leaves in six hours, but he’s well prepared: he’s packing a full rucksack of coffee along with his GPS drones and several high-quality trowels. “Coffee and trowels, man, I can get the rest there. But you can’t get a decent coffee or a good trowel in Ulan Bator,” he says.

Mongolia is the focus for so much of his work, he explains, because it’s one of the places where people and horses are closest today. “Mongolia is a place where almost the whole archaeological record is intertwined with horses in some important way, and significantly for Hoof Beats, the role of Mongolia in the human-horse story has been largely omitted from the story told so far,” he says, pointing out that, even in 2024, there are more horses than humans in Mongolia.

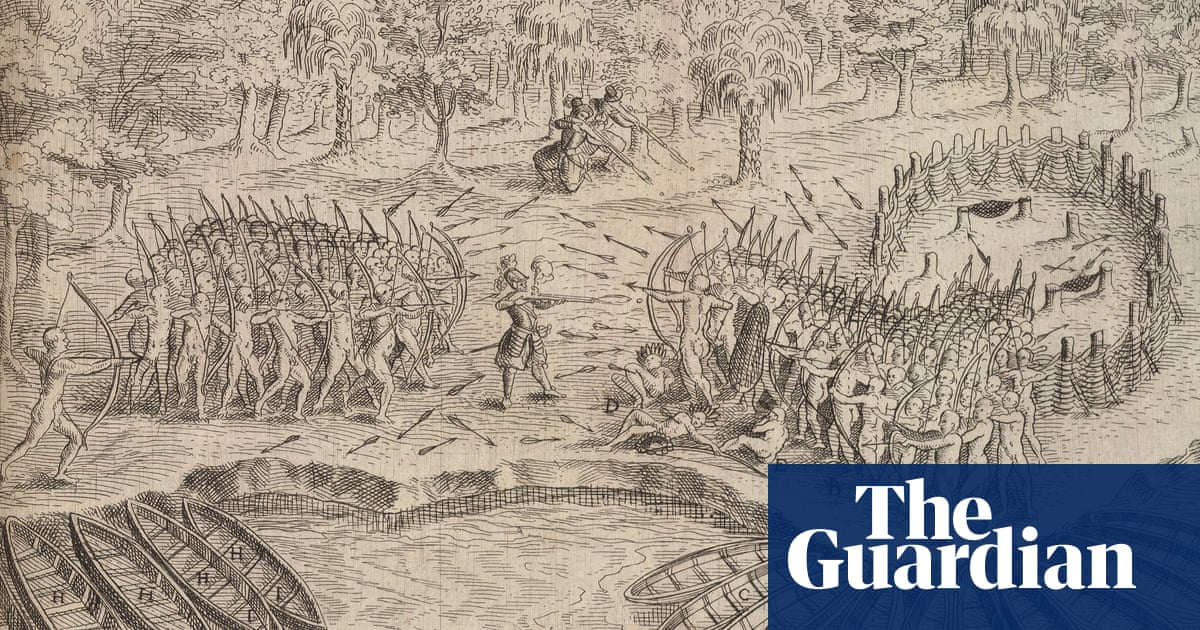

Mongolia, a Buddhist nation between Russia and China, is perhaps most famous for the marauding horseback Mongol hordes led by warlord Genghis Khan in the 12th century. Khan commanded the largest land empire in human history, using vast and exclusively horseback armies of expert archers: they were the world’s most mobile and deadly military unit.

Khan united the nomadic tribes of the Mongolian Steppe and conquered much of central Asia and China. At their peak, the Mongols controlled an area about the size of Africa – thanks, in the main, to their deep knowledge of the horse. Khan’s invasions were brutal and genocidal, but he also abolished torture, forged new trade routes and even created the first international postal system. It was an era of unprecedented globalisation: of ideas, objects, and people, all horse-powered.

The connection between people and horses is among the most ancient connections that we have with the animal world, says Taylor. And some of these connections lie surprisingly close to home for many of us.

In Hoof Beats, he details how a perfectly preserved stone age site, discovered in 1974 in the chalk cliffs of Boxgrove, Sussex, gives us evidence not only of the first human-horse contact in the British Isles, but also perhaps the first proof of human hunting anywhere in the world. Later excavations revealed an almost complete horse skeleton, attacked and killed by early humans more than 500,000 years ago.

A drinking mare was ambushed by a group of early humans, Homo heidelbergensis, using the water’s edge to trap and ambush the horse. The hunters killed and butchered it in situ, carefully removing its spinal column, brain and tongue – prized fleshy delicacies. They cracked open some bones for their marrow, and sharpened others as tools and weapons. And it is bones such as these that can today yield extraordinary amounts of new data when analysed by modern techniques and interdisciplinary science. This archaeozoological approach underlies much of Taylor’s work, since the sites he excavates sometimes offer only fragmentary glimpses of the past.

The Boxgrove site is so perfectly preserved that pieces of flint knapped from larger stones have been fitted back together like a 3D jigsaw, showing the origin and use of each tool. Some were used for scraping the animals’ hides, raising the tantalising possibility that these early humans dressed themselves in horsehide, while hunting the animals using horse bone spears and daggers.

But horses became more than a source of food when they were first domesticated. Where this happened is subject to debate but it is thought to be some time between 3500BCE and 3000BCE. Then, 1,000 years after that, came the invention of the chariot, followed by the emergence of technologies such as the lighter-spoked wheel, the stirrup and saddle, which allowed humans to ride the animals for trade and war. This spread into new territories, new environments or along new trade routes, all of which brought about widespread and revolutionary shifts in human culture, says Taylor.

By sharing technology, ‘Horses were like an ancient internet’

Working with international teams, including geneticists and even dentistry experts, Taylor studies scraps of bone, or sometimes fully assembled ceremonial chariot burials, to understand how the animals lived and died, and from this to deduce if they were ridden, or controlled using bits and reins, or if they pulled chariots or carts with yokes.

By the second millennium BC, horses moved people, goods, languages and technologies into areas they had never before been seen. “Horses are kind of like an ancient internet,” says Taylor.

The search for artefacts exploring horse and human contact has unearthed objects as rare as they are bizarre: the first documented human faeces in the Americas, more than 14,000 years old, was found at Paisley Caves, Oregon, alongside horse bones. The oldest known pair of trousers, 3,000 years old, were designed for and worn by an early horse rider. These were found at a tomb in Yanghai in China’s Tarim Basin in 2014.

Some of the most magical finds have been in Mongolia, including monumental standing stones known as deer stones for their carved adornments featuring the animals. These structures encircle sacrificed horse skeletons, hollow eyes facing the rising sun, buried in full tack alongside their owners and their chariots. There are several thousand such monuments across the country.

Many artefacts have been extracted from deep inverse pyramidal burial grounds in the country’s frozen high plains, says Dr Bayarsaikhan Jamsranjav, a colleague of Taylor’s, who discovered the world’s oldest evidence of mounted horseback riding. In 2016, he found, identified and dated a fully intact 2,000-year-old wood-framed saddle with iron stirrups in a tomb at Urd Ulaan Uneet in Mongolia, which he says was the highlight of his career.

Aside from the academic discoveries, what resounds most clearly through our conversation is Taylor’s deep love of horses: his relationship with them provides him with what seems to be his most intense personal motivations. We discuss the thrill of galloping, of the flowing unity between rider and horse when the animal seems to teach the rider the correct rhythm to experience an ineffable, but terrifying, sense of weightlessness, of effortless flight.

“Yes! It’s one of the purest ways to understand not just another animal and not just the landscape, but also yourself. It really is transcendent. Most people who spend time on a horse will recognise aspects of that feeling, that moment of pure connection between rider and horse. There are very few experiences like it. When I go someplace new, and I’m trying to get a sense of the landscape, riding horses is one of the purest ways to do it, because you feel it rather than know it. You can academically read about things for a long time, but that experience is incredibly important.”

Hoof Beats: How Horses Shaped Human History by William T Taylor is published by University of California Press. Buy it for £25 at guardianbookshop.com

This article was amended on 21 October 2024. An earlier version said that horses were first domesticated 3,000 years ago in the Black Sea region. In fact where this happened is subject to debate, but it is thought to have been some time between 3500BCE and 3000BCE.