In 2005, Sinéad O’Connor and I sat in a dressing room in London together, people-watching and listening, eyeing the music biz swirl around us suspiciously. Neither of us was familiar with the other’s work, which helped us to speak freely, unattached to anything but a shared impression of humanity we both needed to help us with our stage fright.

It was an uncomfortable night, not our show – the Meltdown festival in London, not an event with which we were familiar – so we were jittery, hoping to be allowed to leave soon. In that moment, we were two people, though – not two performers – and we chatted like women on a bus. I didn’t know her music because pop stars weren’t interesting to me, so I didn’t pay attention to them, and she didn’t know my music because nobody but pop stars are interesting to normal people. And she was a pretty normal person, I think, though she’d been accused of strangeness, of craziness, as had I. It’s like somebody somewhere had decided that, having broken too many rules, we fit in no category, and so we were not invited to the party. Having been invited once and met with anger, she felt alienated. Having never cared about the party, so did I, when I learned that it was the only game in town. Alienation helps with clarity, though, as it adds the objectivity of no longer swimming in those waters.

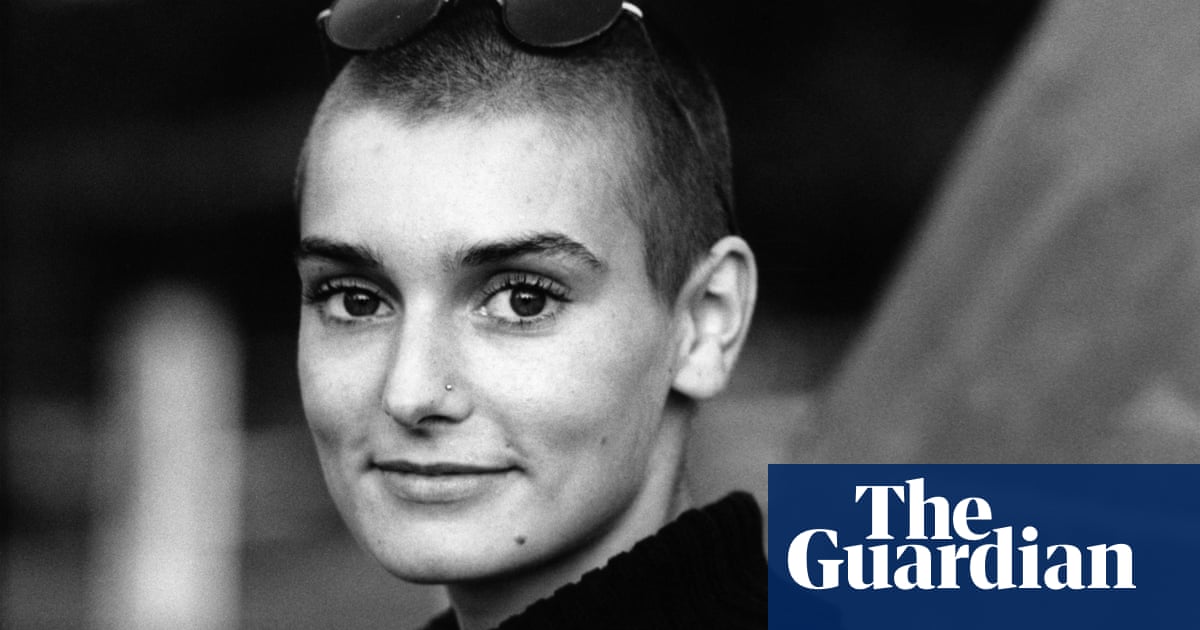

Alienation was only one of the things we had in common: we were also mothers, having had babies and released our first records about the same time, in the late 80s, when we were very young. We were both shy, both outspoken, and we both had resting fear face. And clearly, we were of a different ilk than the rock stars milling around us. I want to say that we were without display, and in that company this quality was very apparent.

She wasn’t allowed to smoke in the dressing room because there were so many vocalists back there, and that was driving her nuts.

“Want some gum?” I asked her as I started fishing around in my backpack for some Dentyne that was at least a couple of years old. I found it and unwrapped a gooey piece for her, which she accepted carefully.

“It’s … old,” I told her. “You don’t have to eat it.”

‘I’m not a musician,’ she announced flatly

Dozens of people talked, laughed, dressed, undressed, fussed and drank around us, while we sat on a small, discarded riser, watching. There was some jockeying for position status-wise for us to watch, and some bonding. Some don’t-touch-me-I’m-famous, some please-love-me-I’m-a-freak. Typical dressing room stuff.

“Where do they learn to do that?” She put the gum in her mouth and nodded toward an entourage actively worshipping the star in the centre of their commotion. The group radiated a strange energy: buzzing and alert, they focused on the star while appearing to deflect stranger danger, keeping people away. It looked like a kind of cellular patterning.

“Yeah.” I watched the huddle jealously guard its nucleus. “Some people learn the narcissist side of the equation and some learn the sycophant side. But it’s the same equation.”

She touched her fingers to her face in a V shape as if they held a cigarette. “Do they even like each other?”

“I don’t know. They seem kind of angry.” The entourage made its way across the room, through other entourages, past bowls of fruit and bottles of wine, and then disappeared through a door on the other side – still buzzing, still deflecting. “What do you think?”

Chewing my terrible Dentyne, she squinted at the door closing behind the group. “I think … that the people who treated me like that were the same ones who ended up hating me.”

I looked at her, struck by this. “Hating you?” She nodded, distracted, and I shook my head. “I’m sorry.”

“It’s because I don’t keep my mouth shut.”

“Oh.” We watched a line of people applying makeup in mirrors, their faces surrounded by hot yellow lightbulbs.

“Why should you keep your mouth shut? What do you say?”

“All kindsa stuff. Stuff I believe.” Staring, blank-eyed, she looked stricken. “Didn’t know you weren’t supposed to do that.”

I shrugged. “Maybe they aren’t supposed to do that. If it’s stuff you believe … seems important to say it. Some people don’t believe in anything. You’re lucky you care.”

She looked at me. “Do you?”

“Care?” She just kept staring, so I kept talking. “I guess, but nobody seems to know what I’m talking about, so … they don’t take offence.”

“Offence,” she repeated, laughing. “That’s what I do. I offend.”

“You’re offensive?”

“Indeed.” She told me a few stories then, relayed a few troubled moments. The seismic activity of a career in the entertainment industry. Maybe ups and downs but more like back-and-forths. Not much of what she said had anything to do with music – more sociocultural, sociopolitical. But she took it all very personally, had never left that almost childlike view, surprised that attracting attention could attract negative attention. Then she muttered something I didn’t get. Something about God.

“God?”

“I always end up there,” she smirked. “Freaks people out.”

I nodded. “Yeah, God’ll do that.” I unwrapped a sticky piece of gum for myself. “But we could use more God here. Maybe choose a different word next time.”

Sinéad laughed loudly, and a couple of people with lipstick and hairbrushes in their hands turned around to see what was funny, smiled at us, then turned back to their reflections. “Life?” she asked.

“Life,” I agreed. “Can’t play music without life.” Speakers on the wall crackled, then beeped, and a voice announced that it was 10 minutes until doors – meaning that the audience would soon murmur their way in, find seats and demand that we all turn sound check into a show together. “Musicians forget that.”

“I’m not a musician,” she announced flatly.

“Oh,” I shrugged, feeling suddenly awkward. “Well, you’re alive.”

She took the lousy gum out of her mouth. “I honestly don’t know why sometimes.” Getting up to wander the room looking for a wastebasket, she muttered, “I’m a mess.”

This is when I realised we were on different sides of something – something I’m only now beginning to understand. My life was private, hers public. She was in light, and I was in shadow. I believed in something she didn’t, and she believed in something I didn’t – our orientations were completely opposed – and I felt for her. The illusory world of attention was equally positive and negative for her, and that caused her a lot of pain. Its bullying was real in her psychology, so she couldn’t walk away from it. And yet she knew something was wrong and railed against the wrongness in that sphere, which set the bullies on a fire that they then set on her. And I could see it eating away at yet another human being – another whole person feeling subject to fake love and real hatred instead of focusing only on music.

“I don’t think …” I tried to find the words that would help and not hurt – not hurt this person I’d known for less than an hour. “I don’t think we can solve these problems. We can wake up and champion underdogs, but people are gonna get pissed. That’s just what happens.”

Sinéad looked thoughtful.

“Sorry, wait.” I spat the awful gum into my palm. “That means drunk here, right? I meant pissed off. Where’s the trash?”

“I knew what you meant.” She pointed to a wastebasket between two of the mirror people. “And we just keep fighting?”

I tossed my gum between a couple of knees as the speakers crackled again, then beeped, then told us that doors were five minutes away. “Sure. Maybe we can’t call it that. Sounds mad.”

Music from the venue began playing through the speakers. Gentle stuff. “Wait. That means crazy here, right? I meant angry.”

“I knew what you meant.”

“We keep helping?” I tried. “Can we call it helping?”

“Don’t say God, don’t say fight,” she snickered.

“Say life, say help.” I smiled. “Problem solved.”

She sighed deeply. “All problems solved.”

“Except you still can’t smoke. And this gum is very terrible.”

We fell back into staring; her resting fear face returned, and mine probably did too. Though my expression was not a life orientation, more of a life irritation, because I knew that truth would return along with real life when I was allowed to walk away from the party. Sinéad seemed to live in a corner of the party, though: believing in its troubles and causing trouble about it. What a thing for a soul to be tasked with. She seemed upset and flailing, but only because she straddled love and illusion, which was a hell of a sacrifice on her part.

I know more about her life and output now, having read many interviews with her: from the late Kate Holmquist’s lovely consideration in the Irish Times of the importance of making garage music in “nowheresville” – an early career kickstart that ultimately gave Sinéad a place on the world stage – to her 2005 quote for Nicholas Jennings (“I’m interested in rescuing God from religion through music”). That one stuck with me, as she has so firmly stated that God is missing in the west, driving her own search for spiritual understanding elsewhere – one that might have helped calm her heart, ease her pain.

But her essence was more vivid to me in that dressing room than in any interview, to be honest. In the person she was, not the persona. “Lost,” I want to say, but carrying the conviction that the lost may be found and could lead other souls to that fight for God, helping them toward life. The “troubled” card is too easy to play in retrospect; after a life has ended, we have the honour of looking back on its beauty, and we should rise to that occasion. Where is the beauty on that path?

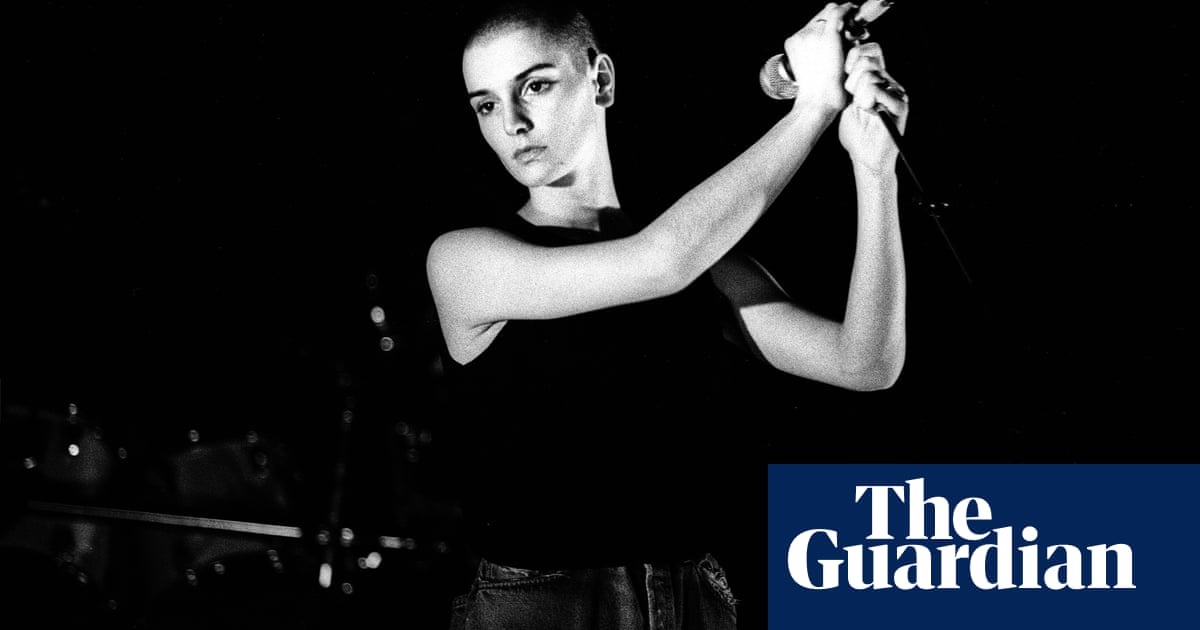

That day, and the day she died, I wished for Sinéad’s sake that she could have lived a life free of judgment: privacy over publicity. In my subculture, for example, a shaved head and combat boots were conforming; her presentation would have incited no reaction. That would just leave her music. Humans have a long, respected history of pulling down corruption and sexism, as long as you’re outside of – above and beneath – the superficial. That’s also where music lies. I wished that she had been rewarded for depth, not breadth. Again: just the music. God is missing; she was right. So, find God in music and believe it. We would all have benefited. A true singer’s power is in their body. These bodies that take the ride with us, she had one and was so willing to share its ride. I wished she could have shouted all that she believed and made only friends, no enemies. I wished that she had never accepted that invitation to the entertainment industry party and, instead, had kept the richness of her own life untainted.

I wished that she could have loved herself and everyone else. I wished that she had absorbed the spiritual peace she fought for. But that wouldn’t have been Sinéad, I guess. So where is the beauty? In all of it: in the pain, the joy, the mess, the person, and her music.

Sinéad O’Connor: The Last Interview and Other Conversations is published by Melville House on 19 November

Sinead O’Connor: The Last Interview by Sinead O’Connor and Kristin Hersh (Melville House Publishing, £13.99). To support the Guardian and Observer, order your copy at guardianbookshop.com. Delivery charges may apply.