This time last year, Mosab Abu Toha was standing in a queue waiting to pass a checkpoint. He had already made the difficult decision to tell his parents that he and his wife, Maram, were leaving Gaza with their three young children; the checkpoint was on the road to the Rafah crossing into Egypt. He greeted people he recognised, tried to reassure his children. And then he was called out of the queue. “The young man with the black backpack who is carrying a red-haired boy. Put the boy down and come my way.”

Abu Toha was born in Gaza and had lived there for most of his 31 years, frequently under Israeli bombardment, but this was the first time he had encountered Israeli soldiers in person. He was ordered, by megaphone, to strip naked. When dressed again he was blindfolded, and a numbered bracelet attached to his wrist. He was sworn at, punched and kicked, including in the face, and forced into a truck; when the blindfold was pulled off, “a soldier is aiming an M16 at my head,” he wrote, a month later, in the New Yorker. “Another soldier, behind a computer, asks questions and takes a photo of me. Another numbered badge is fastened to my left arm.” He spent much of two days kneeling on the rubbled ground.

The ordeal ended as abruptly as it had begun. “We are sorry about the mistake. You are going home.”

Maram had contacted friends abroad, who had applied pressure for his release. Abu Toha has an international profile: as an award-winning poet, published in the US, who received a Harvard fellowship for scholars at risk; as the founder, in 2017, of Gaza’s first English-language library, the Edward Said library; and more recently as an essayist.

His series in the New Yorker won an Overseas Press Club award last year. Here, in unadorned, direct prose full of unforgettable sights and sounds and smells, he has been chronicling his life – and, by extension, what it has been like to be Gazan – since 7 October 2023.

An essay about fleeing his home in Beit Lahia, northern Gaza, was followed by one about visiting it in a lull in the bombing to fetch food from the fridge and sit for a quiet minute among his books, now covered in dust. By the time he was next published, two weeks later, that home, which was also his parents’ home, and the home of his two brothers, and, after 7 October, shelter for his three married sisters and their children, no longer existed.

Then came the essay about fleeing Gaza altogether. “I think about the hundreds or thousands of Palestinians, many of them likely more talented than me,” he wrote, “who were taken from the checkpoint. Their friends could not help them.” Not long afterwards he read in the Israeli newspaper Haaretz of some who had died from the same treatment, in the same detention centre in the Negev. The library he founded is also gone.

Abu Toha is in a hotel room in San Francisco when we speak by video call, partway through a book tour for his second volume of poems, Forest of Noise. He has just been to DC, New York City, Boston, Cambridge and Portland. He will be in Phoenix next, then Berkeley, then France and Spain. “I was at the Harvard bookstore two days ago. And it was fully packed. Even the shelving spaces. So many people are coming, you know, to listen to my poetry, but, at the same time, to listen to the stories I’m telling about the people about whom the poems were written, and some of whom have died, some of whom will die.”

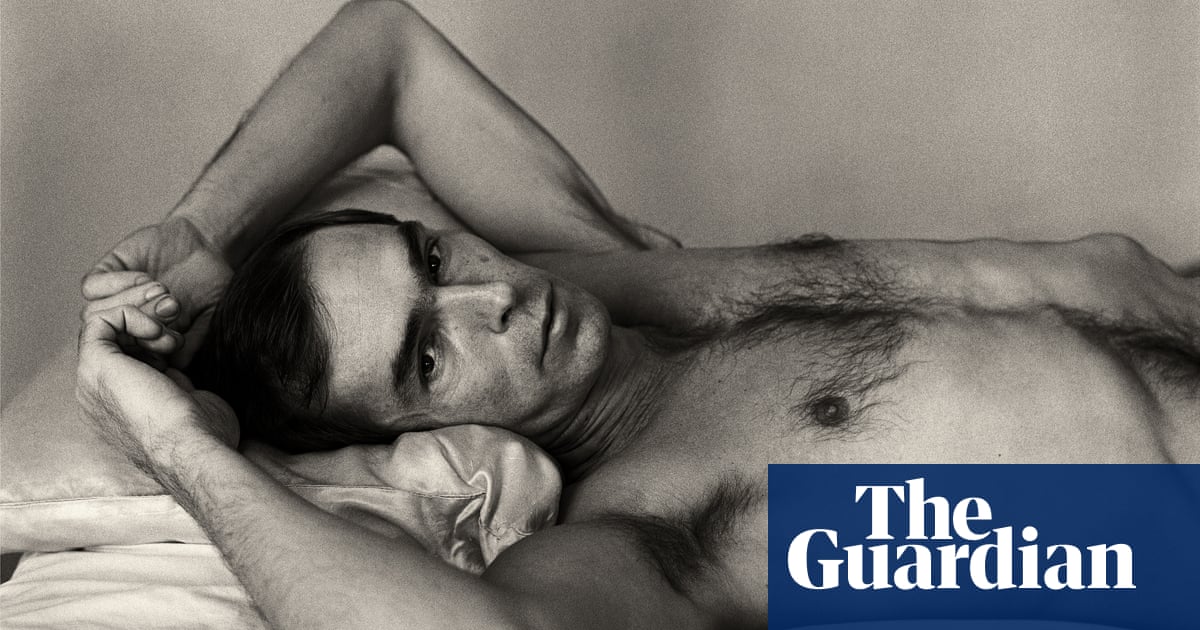

He seems younger than his 31 years, with a polite smile that reminds me of smiles you sometimes see on the news, from an accident victim, or bystander, where the distance between facial expression and the subject of conversation is a gulf. He talks fast, urgently, launching into what he wants to say while I’ve hardly started asking, lit by an intensity that may partly be jetlag, partly character, partly the effect of talking, talking, talking to audience after audience for days, but partly is something else altogether, a kind of sober fever of witness, the compulsion of a bright-eyed Mariner.

When he rises to draw the blind against the California sun, I see the front of his hoodie is emblazoned with a line from his first collection: “A rose shoulders up.” (“Don’t ever be surprised,” reads the poem, “to see a rose shoulder up / among the ruins of the house: / This is how we survived.”)

His poetry, and his prose, are full of these fragile mundanities – old rugs, the smells of food, tea on “a table under the orange or the guava tree”, his brother-in-law Ahmad’s cornfields. When a bomb hits a neighbour’s house, in his first, pre-7 October, collection of poems, Things You May Find Hidden in My Ear, he is surprised: “I never knew my neighbours still had that small TV, / that the old painting still hung on their walls / that their cat had kittens.”

Abu Toha was born in a refugee camp, Al-Shati, but in 2000, at the beginning of the second intifada, the family moved to Beit Lahia, a border town in northern Gaza. His parents “planted fruit trees – guava, lemon, orange, peach, and mango – and vegetables”. His father raised hens, ducks, rabbits and pigeons. This move, “from a very, very compact place to a wide area of land,” is, he thinks, what made him a poet. Suddenly “I could see the sun clearly. I could see the clouds. I could see the plants growing.”

After he married in 2015, “I built my apartment on top of theirs. My wife and I could see the border with Israel out our bedroom window. My children could see our neighbour’s olive and lemon trees.” Blossom, puppies, a mother breastfeeding; “rain waters the stories that sleep on the old, tiled floor”, as he puts it in Forest of Noise – but also, this being Gaza, “the drone [that] watches over all”.

“The poems are about things that the news fails to capture,” he says now. On the news “maybe if someone is lucky, they would say their names or maybe the family name or the area where the bombing took place. But what the media fails to do is tell the stories of these people who got killed.” Palestinian culture is already communitarian, everyone bringing food after a death, for example, or for a wedding, living in multi-generational homes; in the camps, where two people often cannot pass through an alley abreast, this is intensified, and since 7 October, more intensified still, because “when Israel invades an area, people tend to move and stay with other families”.

Last October, “thirty-one members of my uncle’s family were killed in one airstrike. I mean, the whole family, the grandfather, the children and the grandchildren. Only two babies survived with one mother.” A few weeks ago he posted online: “My aunt’s house and her husband’s family are now besieged inside by tanks and soldiers. The Israeli soldiers are firing at the ground floor. She has five children and there are more than 30 persons in the building, mostly children. The house is opposite Shadia Abu Ghazala school in Jabalia. Please help.”

Twenty hours later, he says, “the house was bombed and my aunt lost one child, Sama, seven years old, and still under the rubble until now are about 16 people, including my grandmother’s sister, who I used to call grandma.”

Two weeks ago, his family were on a train from New York City to Syracuse, where they are currently living, when they heard that 25 members of his wife’s uncle’s family had been killed. This is one of the reasons being away from Maram and his children for the book tour makes him anxious, he says: this can happen at any time, to anyone they know, and they need to be together to face the news.

And, he says, “I know not only the people who live in my neighbourhood, but throughout the city where I lived. In Beit Lahia, I can walk in the street and name the people in each house. I know the kids, to which school they go, and when they go to the beach.” He was a student of English language and literature at the Islamic University of Gaza, where his interest in English poetry was sparked by reading the Romantics, so I mention John Donne: “No man is an island / Entire of itself; / Every man is a piece of the continent, / A part of the main.”

“Yeah yeah,” he says. “The loss that we are facing is not only individual loss. It’s not personal loss. It’s a collective loss. When we lose a family, it’s my family. When a house is bombed, it is my house.”

He was interviewed on BBC Newshour when his wife’s relatives were killed, and was told, “and I quote here, that the Israeli army said they carried out a ‘precise airstrike’. The next day, I opened my phone. And I found this.” He leans into the screen to show me. “This is a house. And this is another house, you see? This is a ‘precise airstrike’ on five houses. So whoever they are targeting existed at the same time in five houses.”

And, by the way, the aftermaths have changed, he says. There are so few emergency personnel, and they also have been targeted. Now neighbours dig through the rubble with their hands. And Abu Toha gets texts and calls, begging him to use any connections he has – “not asking me to end this. No, they asked me if I have some people that I know who could let some ambulances through to transport the people who were injured.”

This is something that runs through the poetry, too, this sense of shrunken horizons. It took weeks for Abu Toha to begin to grasp the size of America when he first arrived, Gaza being a speck in comparison (he was also terrified the first time he heard a commercial jetliner taking off. At 27 he knew only the sound of F-16s. He was eight before he realised, watching an Apache helicopter smash a rocket into a building, that this was perhaps not quite normal, and not exactly safe).

Since then he has lost close friends, and at 16 was wounded himself, when he was on his way to buy some eggs, and shrapnel sliced through his forehead, neck and shoulder. That time there was an ambulance. “Someone throws a corpse in next to me. / The body burnt, maybe no head. I don’t look at it. / The smell is so bad. I’m so sorry, whoever you are.” The English department where he studied language and literature at the Islamic University of Gaza was levelled in 2014, a month before his graduation.

“Families of the dead attended,” he wrote in his poem Palestine A-Z, “to receive not a degree, but a portrait of their child.” He rescued a Norton Anthology of American Literature from the rubble, the irony of which was not lost on him, given who funds many of the bombs.

He thinks now that he didn’t really have a childhood, not as those in safer places might think of childhood, a time of possibility and play. In a place where nearly 50% of the population is under 18, a new acronym has become common: WCNSR (Wounded Child, No Surviving Relatives).

This was in the end why he and Maram decided to leave. “I mean, my son who was eight years old should be playing in a park, should be in school, should be watching movies, should be playing with other children. But instead, he was looking for firewood and cardboard boxes, you know, to help his mother and me bake or cook food.” In My Son Throws a Blanket Over My Daughter, he describes his then-five-year-old trying to protect his four-year-old from the bomb they can hear falling. “You can hide now, he assures her.”

Part of the attraction of the Romantics was how they expanded space. “’I wandered lonely as a cloud’ – I cannot forget this opening line,” he told an interviewer a couple of years ago. “It gave me another world to think about and live in.” His new book is fronted by a phrase from Audre Lorde, “Poetry is not a luxury”, and I ask what that means to him. I had expected something along similar lines – but no. This poetry is an act of witness, of reportage. “It’s not a luxury because of the things that I’m writing about. And sharing it with other people is not a luxury,” but a vain attempt to say, this happened, “make sure it doesn’t happen again. But it happened again and again.” And not just the bombing in general, he says, but moments in that bombing.

He reminds me of his poem The Moon – almost unreadable in its open-eyed bleakness – about a small girl lying dead next to her father on the asphalt, and a hungry cat pacing. “And just three days ago, a video was uploaded from my city of two cats eating from a corpse that was left in the street. You see the cat? No? “OK. Let me show you the video.”

I stare at it flickering through the interference of two screens, though at first I have to admit I am just saying yes. I don’t want to look. But that doesn’t feel right, so I look properly and there is the cat’s head rising and then dipping again. “There is that definition of poetry, you know, the best words in the best order. And for me, as a Palestinian poet, I would add one other thing, which is in the best time. I mean, I can’t wait for my poems to be published two years later.”

So he puts them on Instagram. His friend Refaat Alareer did the same with one of his own last October. Abu Toha wrote a response in November. By December Refaat and many of his family were dead.

It’s poetry as memorial, too. In a poem that responds to Elizabeth Bishop’s No Art (“The art of losing isn’t hard to master”), Abu Toha notes that as well as friends, and a city, he’s lost “a language to fear”. What does this mean? It’s very striking. “I mean …” he slows down, thinking. “We are so traumatised that we have stopped using our language to describe what’s happening to us. For example, when my wife lost her uncle and all his family, she just cried for a few minutes and then stopped. She never talked about it. We fear even talking about the dead because we know 100% that the next day we will lose more.” And anyway, what is the point, when the person you tell is likely to have lost even more than you?

Now people bury their dead, “and then the next day they take their bucket and look for a tap to fill it. Stand in queues, you know, to get a loaf or two loaves of bread. We don’t even sit and give them their time, you know, remembering them and paying them tributes.” A sudden rush of urgency – and “this is terrifying, this is terrifying! Sometimes I forget that I lost a relative of mine. Last month I told my wife: ‘You know, Maram, we haven’t talked to Aunt Aliya for some time,’ and she said: ‘Oh, did you forget she passed away?’”

He is concerned about generational forgetting, too. He grew up with stories of his paternal grandfather, who left his home in Yaffa in 1948 believing he would be away for only a few days, and was never able to return, and of the key to the house the family have kept since; his daughter is named Yaffa. But his children – will they ask only about the 2009 war, or 2012, 2014, 2021, 2024? They will loom so large it will be hard to see around them.

“On the morning of October 7th,” he wrote in the New Yorker, “when Hamas began to launch rockets at Israel, I was wearing some new clothes, and my wife was taking a photo of me. The sound of rockets made Yaffa cry, so I showed her some YouTube videos on my phone. My father and brothers were on different floors of the house, and we started to shout a conversation out the windows. What’s happening? Is this some kind of test?”

People in Gaza are angry, he tells me in an email later, at both Hamas and Fatah, because of the political rift that started especially in 2007, a year after Hamas won the election and the siege began – “a rift that cost us so much and which has been fuelled by Israel and the west”. But mostly, he says, they are angry about being abandoned by the world, ever since 1948, about not being recognised “as a people with human and political rights to be protected. How many UN resolutions have been dismissed?” As for the situation now, he says, in our interview: “How many times has the United Nations warned that Gaza would be unlivable by 2020? What has the world done to change this?”

So, too often, the anger, he says, unheard, now turns inward, at each other, to fighting over food, over water, over aid. “Just imagine you are now in London and you are allowing just five trucks of food into the city. Of course you would take to the streets and maybe fight with your neighbour because you want to feed your children.”

As for him, how is he coping? His parents are still in Gaza, his sister is expecting to give birth as we speak. “Maybe she gave birth today? I don’t know whether she had access to any ambulances or any hospitals, etc. But I, as a human being, I feel like I’m on the run. I’m just running, running. Reading and translating and posting and giving readings and talking to people and giving interviews. I can’t stop, because if I stopped, I would fall.”

Forest of Noise is published by Fourth Estate (£10.99). To support the Guardian and Observer, buy your copy from bookshop.theguardian.com. P&P charges may apply.