I traveled to Afghanistan in 2015 to film a documentary about the United States drone war. When my production partner and I inquired about kidnapping insurance, we were told that it would cost more than $20,000 to cover the director of photography and me. We couldn’t afford such a high premium and declined the offer.

We did, however, take other precautions: worked with a well-vetted and experienced local team, dressed and traveled like Afghans, and stayed in safe and unmarked guesthouses. We also purchased from Reporters Without Borders health insurance for high-risk countries that covers emergency evacuation and repatriation in case of amputation or death.

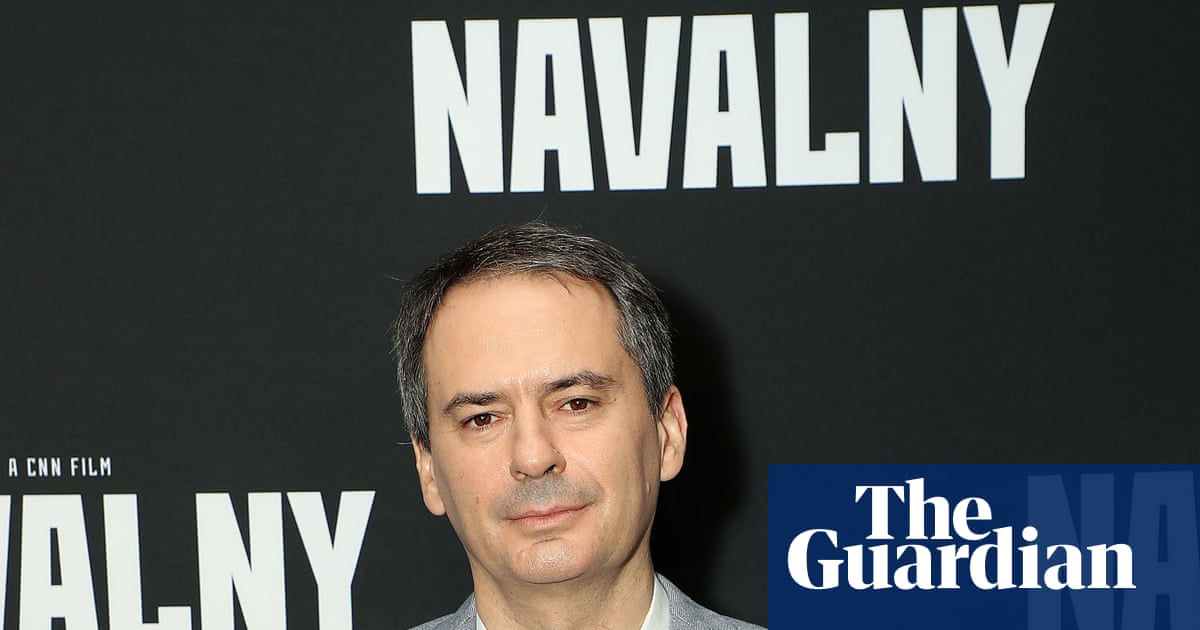

We were aware of the risks when we traveled to Afghanistan. Everyone on my team knew journalists who had been kidnapped in different parts of the world. Some of them survived; others did not. The subject of this film, Michael Scott Moore, is one of the fortunate ones: He made it out alive after being held captive by Somali pirates for almost three years. (He is publishing a book about his ordeal next year.)

Much of the credit for Michael’s freedom goes to his mother, Marlis Saunders, who led the negotiations with the Somali kidnappers and collected a substantial sum of money from private sources and foundations to pay her son’s ransom.

While it might seem unusual that a mother has to deal directly with kidnappers to rescue her son, the United States’ reticence to negotiate on behalf of hostages makes the involvement of a captive’s family in the negotiations all but a requirement to secure safe release.

The United States and Britain have the strictest no-concession policy of all Western countries — and largely comply with it. By contrast, continental European countries like Germany and France, while not acknowledging payments publicly, are known to have paid ransoms for their citizens, freeing them even from the clutches of terrorist groups like Al Qaeda and the ISIS (and helping fund those groups’ bank accounts in the process).

These divergent approaches seem to have a profound impact on the outcome of a hostage case. An insightful examination by the New America Foundation titled “To Pay Ransom or Not to Pay Ransom?” found that while a strict no-concession policy does not appear to lower the number of kidnappings, not paying ransoms increases the likelihood that hostages are killed. Or to put it differently: An American or British hostage has a much lower chance of survival than a hostage from continental Europe. While Americans account for roughly one out of five Western hostages since 2001, they make up half of the hostages who were murdered by their captors. One of them was the journalist James Foley, whose mother, Diane Foley, has criticized United States hostage policy for years as being inconsistent and unjust.

Some people will ask: Why should the government be responsible for paying ransoms for journalists who were kidnapped abroad? My question is: What is the alternative? To let people be murdered while conducting a job that plays a crucial role in democracy and education? Or should journalists not travel into conflict zones and disaster areas, not cover America’s wars and interventions worldwide, not shine light on global issues like genocides and human trafficking? We need to consider: How else do we get important, independent information from outside our comfort zones if not from journalists, both American and foreign?

Journalism is an inherently risky profession, and as news organizations close costly foreign bureaus, our bounty of foreign news reporting shifts to freelancers, who often set out into dangerous settings unsupported and without proper training.

(Major news organizations, like The Times, traditionally send out their reporters with support that freelance journalists lack.) War reporters are well aware of the dangers they face covering conflicts, and they make threat assessments and carefully consider worst-case scenarios. They also take responsibility for the consequences their decisions have for their families and other people involved in rescuing them. The New York Times