On the evening of what looked like it might be the most polarized election in the 30-year history of Brazilian democracy, it was clear that a big churn of the existing political order was coming. But the figures pouring out of television sets across the nation were astounding.

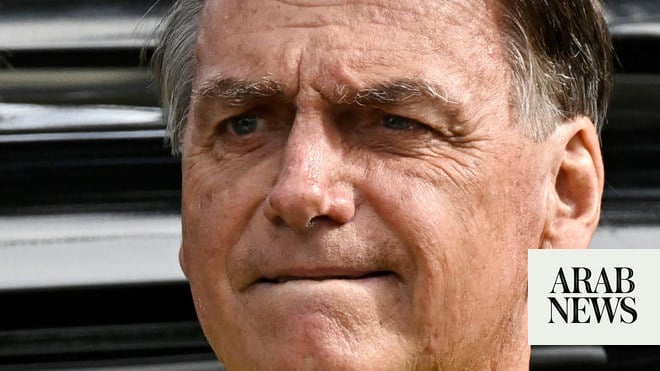

At 7pm, with two-thirds of the votes counted, the frontrunner among the candidates for president — the veteran far-right congressman and former army captain Jair Bolsonaro, 63 — led, as expected, in the polls. But, most consequentially, Bolsonaro had received more than 49 percent of the votes counted, putting him within a hair’s breadth of the absolute majority that would give him instant victory.

This was an astonishing electoral performance from a politician whose long career — he has been a deputy in Parliament since 1991 — had hitherto only been remarkable for its lack of distinction. It confirmed that Brazil is now part of a global reorientation of democratic politics toward the right.

Over in Barra da Tijuca, a quiet neighborhood in the western part of Rio, where Bolsonaro lives, people began to flock to the politician’s residence, many of them wearing the green-and-gold football jerseys of Brazil’s national team.

I recalled a conversation in a bar that morning with a man in his 70s, a retired helicopter pilot, who said he was voting Bolsonaro because “he has a military background and will bring back discipline to our country.” To my question about Bolsonaro’s chances in a probable two-man run-off, he snorted. “Run-off? Bolsonaro’s going to win tonight.”

At one stage, it seemed his prediction might be proved right. But the votes from the north and northeast were still coming in and, slowly, Fernando Haddad, the inexperienced candidate from the left-wing Workers’ Party (also known as PT and which had held power between 2002 and 2015 before its president, Dilma Rousseff, was controversially impeached for corruption) began to drag Bolsonaro back.

Bolsonaro’s share of the vote fell to 48, then to 47. Finally, just before 9pm, the TV channels were able to announce what every voter of a liberal mentality in Brazil had been praying for: Bolsonaro and Haddad would go head-to-head in a second round of voting on Oct. 28. Bolsonaro had won the battle, but not yet the war. Haddad and the PT had lived to fight another day.

Brazil has taken its tryst with Bolsonaro too far to change track. Come the Oct. 28 run-off, the nation must orient itself to the strange new world he seems destined to bring in.

Chandrahas Choudhury

But it was lost on no one that nearly 50 million voters, or about 46 percent of the total, had put their faith in Bolsonaro’s provocative messages of greater privatization of the economy, cuts in welfare spending, and a harder line on crime and gang violence. These were combined with a moral crusade painting the entire political establishment as a pack of rats; and especially the Workers’ Party as the center of corruption and decadence in modern Brazil. Bolsonaro’s Social Liberal Party also soared from eight to 52 seats in the lower house of Congress, second only to the far more established PT’s 56.

Pre-election opinion polls correctly showed Bolsonaro to be the frontrunner in the race, but also the candidate with the highest rejection rate — that is, those who were not for him were resolutely against him. So it had seemed that, if Haddad could run Bolsonaro close in the first round, he might then, as a more centrist voice, slip past him in the second. Unfortunately, that now looks unlikely. Few of those who voted for Bolsonaro are likely to change their minds now that he has victory in his sights, and he only needs to add another 4 percent of the mandate to take charge in Brasilia next month.

Yet Bolsonaro cannot afford to be too sure. Haddad was a late choice as his party’s nominee for president, after an electoral court ruled in late August that former President Lula da Silva could not contest the election because of his indictment on a corruption charge.

Haddad’s 29.3 percent share of the mandate is not small for a relative neophyte in national-level politics (he was formerly the mayor of Sao Paulo). He comfortably beat veteran presidential contenders Ciro Gomes (12.5 percent of the vote) and Geraldo Alckmin (4.8 percent). That can be attributed in no small measure to Lula’s continuing influence in Brazilian politics.

But can Haddad pull off a miracle? His ability to do so depends in some measure on the responses hereon from Gomes and Alckmin, whose supporters must now transfer their votes to either Bolsonaro or Haddad. Neither, it seems clear, will side with Bolsonaro.

If Haddad could bring together these candidates and their parties in some sort of grand pro-democracy coalition between now and the run-off, he might stand a small chance of taking Bolsonaro to the wire.

But the problem is that Sunday’s vote shows that democracy itself has acquired a bad name in Brazil. The polarization of Sunday’s results points to a giant faultline emerging in Brazilian society; a growing lack of faith not just in the political class but in the system itself — and a search for extreme solutions. There is little common ground between the two fronts. If anything, Haddad’s attempt to stitch together a coalition could send undecided voters further to the right.

The writing on the wall seems clear. Brazil has taken its tryst with Bolsonaro too far to change track. Come Oct. 28, it must orient itself to the strange new world he seems destined to bring in.

Chandrahas Choudhury is a writer based in New Delhi. His work also appears in Bloomberg View and Foreign Policy. Twitter: @Hashestweets

Disclaimer: Views expressed by writers in this section are their own and do not necessarily reflect Arab News" point-of-view